Numlock News: Sabrina Imbler on How Far the Light Reaches

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition.

This week, I spoke to Sabrina Imbler, the author of the new book How Far the Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures.

Imbler’s a writer at Defector and is one of my favorite science writers; they specialize in coverage of new science being done in the animal kingdom, and I have been really excited for the book out this week.

The book is ten essays that examine the lives of animals that live in the ocean, and explores how their lives and Sabrina’s reflect one another in really compelling ways.

The book can be found wherever books are sold, particularly independent shops, and Imbler can be found on Twitter and at Defector.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Sabrina, you are the author of How Far the Light Reaches. You cover science and particularly animals and fascinating things about them. I guess what drew you to this topic? What drew you to the deeps?

The deeps of the ocean?

It's funny, I get this question sometimes and I wish I had a short answer. I grew up in California and I was lucky enough to go to the beach a lot as a kid, and go on tide pooling field trips, which were very formative.

I also grew up going to the Monterey Bay Aquarium. I feel like it's hard to go to that aquarium, which is so enormous and so beautiful, and not fall in love with the ocean. I also grew up with a really crippling hay allergy and pollen allergy. Whenever I would go out to a mountain or a hike, I would have an asthma attack, so the sea was both a thrilling place of a way of connecting with the natural world and also one that I could survive and not wheeze at.

I'm really drawn to creatures that are very different from me, me being a human, not me personally. And the ocean is full of very, very different kinds of life.

Your day-to-day beat, you're a journalist at Defector and you cover a lot up and down the animal kingdom. I thought it was really cool that for this book you really just focus on one biome, so to speak, and just the vast diversity of stuff in the sea. What was the first animal that you looked into? What drew you to this topic?

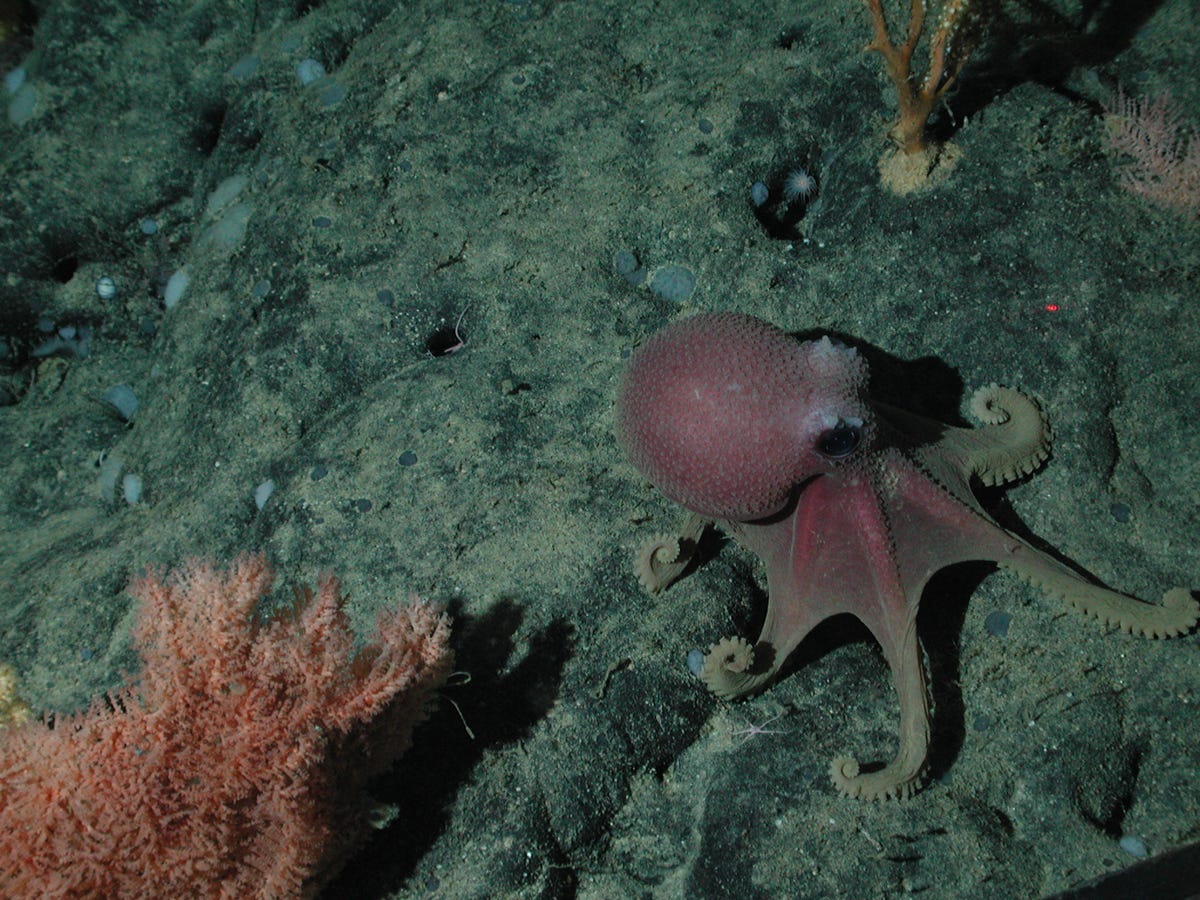

The first essay that I came up with for the book was the one about the octopus, which is an essay about this deep sea octopus, Graneledone boreopacifica. I learned how to pronounce that with the audiobook. She was this deep sea octopus living off of Monterey Canyon by California, and scientists basically observed her over the course of several visits, brooding her eggs for four and a half years without eating, which just means sitting on her eggs and truly not eating for four and a half years. It's stunning.

At the time I worked for Wirecutter and I was reviewing toasters and air conditioner brackets and I didn't have a place really to write about this octopus. I wasn't a science journalist yet, I just wanted to be one. I was bummed because this is the most exciting animal story I’d learned of for quite some time, so I just thought about her for years. When I saw that this online magazine called Catapult had a call for columns, I was like, "Oh, maybe I could write a column about sea creatures and what they make me think about in terms of my own life."

I went to college in the personal essay boom of the internet. I think that was how my brain worked, of, “Here's a cultural object, let me insert myself into it.” I found it really generative to think about what are the parallels between this octopus and me, and why do I find myself so fixated on this octopus? It was a really cool way to talk about my own relationship with disordered eating, and my mother's relationship with disordered eating, and what it means for a body to starve.

And also, just get into the weird metabolics of the deep sea, where creatures can go months without food, and that's just a normal way of life. Because a lot of creatures down there are sustained by marine snow, the falling flecks of waste and flesh and poop that fall from creatures that are more near the top. Or they depend on these random windfalls of food, like a whale dying somewhere, and a community will flock to the whale and be sustained there for years. It was the octopus that was my portal into the book.

That is cool that your “great white whale” was actually an octopus.

One thing that I'm always interested in is how this marine life intersects with humans and human life and human interaction with the ocean. You have at least one, if not more, stories about how human intervention has potentially changed migration routes and things like that. How would you say that humans factor in this story?

I mean, yeah. I guess twofold. I guess I am the most prominent human, although in my day to day I'm not really materially affecting the lives of the creatures that I write about.

I wrote a lot of this book during the pandemic and it was both transformative to be able to think about, this is the furthest place from my New York apartment, being in the ocean, being in the Salish Sea, being at the bottom of the ocean off of California.

It was also a sad process oftentimes in reporting this because humans have made the conditions that so many of these species depended on for so long unlivable for some of the creatures in this book. From the Chinese sturgeon, whose longstanding migration route to breed and land has been stoppered by dams, which also raised the temperature of the river to conditions that are not really amenable to breeding, to these killer whales off the coast of British Columbia, which are one of the most endangered populations of the marine mammals in the world and are really suffering and trying to find salmon which we have depleted.

It felt like for every creature that I could write about, there was also a, "Well, time to talk about how we ruined their everyday life!" or "made them alter this way of life that has been so successful for them for thousands of years." I don't know, I felt a lot of guilt while writing the book for everything that we humans have done.

I think something that I held on to deeply was a hope that I have that the book allows people to feel a deeper connection to the ocean and the different creatures inside of it. Because it's easy to see birds, it's easy to see insects, it's easy to see dogs, but a lot of people don't have that sort of immediate access to the ocean. I was hoping, if you feel like your survival on this planet is not necessarily tied to this whale or this octopus or this jellyfish, it really is. We all live on the planet together, and we all depend on the planet staying functional for a long time.

Let's talk about the connection a little bit. One of the hallmarks of really good science writing, really good animal writing and the stuff that I've seen in your work time and time again, is that you really do try to get a sense of empathy with not just these animals, but also just things that you would almost never in your day-to-day life attempt to empathize with, like gelatinous chains of organisms and things like that.

The traditional way of building connection with creatures is anthropomorphism. Thinking about, how does this animal remind me of myself? There are definitely examples of that in the book; I talk about this famous killer whale from the population of Southern Residents called Tahlequah who grieved her calf for 17 days by carrying the body of her calf on her nose, which is such a heartbreaking story. When it came out, people around the world really latched on to it because it's like a mother grieving her calf.

That strategy, there are obvious pitfalls in that. An animal's never going to be a perfect corollary to your life, and doesn't exist to help you explain your own stuff. But it is an even less helpful strategy when you are talking about, as you said, a gelatinous chain of animal that's mostly water and has really no face, no recognizable sexual experience in the world. I found that it was really inspiring to try to look at these creatures that really are so unlike me in my day-to-day experience and my body plan and the way that I think, and to really try to find points of not just similarity, but resonance. Of how in my life do I feel in the case of the self, which is both a colonial organism — many individuals — but also all those individuals are just one organism at the same time. Just thinking about this creature, I was like, "At what point in my life do I feel like I'm part of a super organism? Do I feel like I'm a part of a colony?"

I thought about marches that I've been in, or when I go to the beach on Pride, and I'm in this big swarming mass of people. And once the sun ducks under the cloud, we'll all get cold, and collectively shiver. I don't know. It was really helpful to think, "How can I be more like these creatures that are so different as opposed to how can they be more like me?"

Crowds have an energy all of their own. They have a mind of their own, as we say, time and time again. That's a really cool comparison.

We don't tend to have an innate sense of empathy with gelatinous clones floating about in the sea so it's very, very cool when you're able to kind of put that together.

I really feel like you can build a connection with any animal. It just requires us sitting with it, looking at it, and just trying to understand how it lives its life as opposed to really being, "This looks so weird. Why does it not have a heart?"

You don't need a heart to be really cool.

The book is How Far the Light Reaches. It's out this week. It's A Life in Ten Sea Creatures. Did you come away with any particular empathy or affection for one of the sea creatures in particular?

Oh, that's a good question. I guess the creature who I feel like I wrote about in the most direct parallel to my life are these hybrid butterfly fish, which are a hybrid animal, the product of two different species reproducing.

We do that sometimes intentionally; we'll make a liger out of a lion and a tiger, or a mule. But hybrid butterfly fish and lots of other hybrids in the ocean are the product of random chance, because a lot of fish reproduce using external fertilization. They just eject their gametes and whatever meets in that cloud might become a fish one day. There are a lot of really random serendipitous hybrids in the ocean that don't necessarily reflect that species might be interbreeding and forming on an evolutionary track to form a new species. It's just kind of random! It's just happening. There are these brief moments of pure chance that are now embodied in a fish.

I just felt very deeply about, I was reading about this butterfly fish because the essay is about my experience as a mixed-race person, and my longstanding quest to find a word to describe myself, which I still don't really have. I've floated between lots of different ones in my life, going from "half-Asian" and then being like, well then what's the other half? "Half Asian, half white?" And then finding a home in the word "hapa," which is a native Hawaiian term that is not mine to use.

As I was thinking about all the different words that I've tried to find as to slot myself into these different categories, and seeing the way that scientists too would also try to slot these fish into understandable and legible categories, I just felt like a lot of empathy for this fish that maybe can just exist as something that doesn't need to be labeled. Just a product of pure chance, just going about its day in the ocean. I think I really fixated on those fish and the ways that we talk about them.

That's really beautiful. I love that.

Well hey, thanks again for coming on. It has been terrific to have you. The book is How Far the Light Reaches. Where can folks find it and where can folks find you?

The book, please order it at your local bookstore or bookshop.org. Don't order it from Amazon if you can. I'm doing a launch at The Strand on December 6th in New York City. And then I also have a reading at Yu and Me books on Tuesday, December 13th, then I'm doing another reading in person in New York on the 14th at P&T Knitwear with some amazing writers, Gretchen Felker-Martin, who wrote Manhunt, and Luke Dani Blue. I have some virtual readings, but you can find all of that information on my Twitter for as long as Twitter is around.

My handle is @aznfusion, like Asian fusion, which I came up with when I was younger and I was like, "Aha, like the cuisine." And now I'm kind of stuck with it.

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Thank you so much for becoming a paid subscriber!

Send links to me on Twitter at @WaltHickey or email me with numbers, tips or feedback at walt@numlock.news.