Numlock Sunday: Alissa Wilkinson talks about 'Salty'

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition.

This week I spoke to culture writer Alissa Wilkinson, who wrote the new book Salty: Lessons on Eating, Drinking, and Living from Revolutionary Women, out this week.

You might recognize Alissa from her work at Vox. I really love her culture journalism and have been looking forward to this book since it was announced. It takes the view of a dinner party and profiles a number of fascinating women through history through the lens of food and a party. It’s a really charming read.

We spoke about why food is such a great lens to view people we can’t meet, how Hannah Arendt’s radical views on friendship got her through unpleasant times, and some of the stories of particularly resilient people in the book that might give people encouragement in times of uncertainty.

Salty can be found wherever books are sold, on audiobook, and Wilkinson can be found on Twitter and Vox.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Alissa Wilkinson, you are the author of the new book, Salty. It's basically a dinner party of a number of fascinating figures throughout recent history. What drove you to write this book and take this angle?

Yeah, there were a couple reasons. One is that I've always really been fascinated by just biographies of people, especially women from history, because I think that a lot of times we're familiar with people's work or maybe we've heard of them, but the details of their lives are always very interesting to me. At the same time, biographies are very hard to write and often very dry and full of details. So I started thinking about this as a dinner party, because I think that what I really wanted to do is get to know these people, get to know what's in their heads, what makes them tick, what are the things that I can learn from them? And if I'm structuring it as a dinner party, then maybe I want to do that through their relationship to food and drink, whatever that means.

I ended up with a group of women, all from the 20th century, all of whom have passed away. We know a lot of things about their lives, but they're a diverse group; they're activists, they're writers, some of them are food writers or chefs, but a lot of them aren't. Novelists, philosophers, just a whole battery of people who I wanted to get to know better, and I really feel like I did that. And in the process, I hope I'm able to introduce them to friends. I structure it as a dinner party because I'm hoping the reader will feel like they were invited to come listen to these women tell their own stories.

I love it. It's a great read. I really liked how much it was about food in a way that was almost like a take as well on just the genre of work that is a cookbook. I found it remarkable how often the women that you profiled had a cookbook in them at one point. I liked how it treated it as a medium in its own right and not just a list of recipes.

There are nine women in the book and I'm now counting in my head, I hope I'm right, but I think five of them did actually end up writing cookbooks at some point, but they're not all cookbook writers. One of them is Laurie Colwin, who wrote popular fiction in the '80s and these very domestic stories, but she did wind up writing two books about cooking, that are like memoirs a little bit and a cookbook. It's just a fun read. One thing that I found out that a lot of people are surprised by is that Maya Angelou, who is the last chapter in the book, wrote two cookbooks.

Yes! That's why I want to ask about it!

Surprisingly, right? And they are delightful. They're full of the stories that she tells and if you read her books, they're full of food. So she reverse-engineers it and gives us the recipes for those foods, but she also was just a famous host in her own right and loves to eat, and sometimes wrote poetry about this. We get that from her books.

I have Alice B. Toklas, who, of course, did write famously a cookbook, but she also is much better known for running Gertrude Stein's life and also being an artist in that way in her own right.

We also have Elizabeth David, who was as much a travel writer as a food writer, and Edna Lewis, who wrote some really influential cookbooks, but is mainly important because she totally revolutionized the way Americans looked at Southern food. She also was a chef at Gage & Tollner, which is this famous Brooklyn restaurant, for years. That was a really fun way to write the book. I decided to put my own recipes into the book, even in cases of people who didn't write a cookbook, like maybe the filmmaker, Agnes Varda, I was able to bring my own experiences and her interests and proclivities into it and come up with a recipe that I thought befit her, which in this case is a roast chicken with potatoes, because she was pretty obsessed with potatoes.

That was the methodology, and I will say going into each chapter, I really honestly didn't always know what the food relationship would be. As I was researching their lives or reading their books, I was looking for that connection. It's always there, because food is something that we all do and eat and think about and all of those things. I was able to have a really interesting window into their thinking.

A window is a great way to phrase it, just because I was struck by how it didn't seem like a bit, it didn't seem like you were reaching for it; it seemed like food very clearly revealed itself to be a very essential part of all of these women's lives in a way that I think really dovetailed super well with your approach to the book.

Yeah. I mean the hardest two, I have a chapter on Octavia Butler, the sci-fi fantasy writer who really wasn't much of a foodie herself by all accounts, but she actually ends up using food in some really interesting ways in her books, in her novels, and it's used as a tool to show something about colonialism, equality, all of these interesting things. And then Hannah Arendt, the philosopher, is not known as the foodie, but all of her thinking just hashed out over cocktail parties and her apartment.

Tobacco is technically a vegetable.

Yes, that's true. They drank a lot, so I have a martini in there. It was just a really fun way to try to dig into their lives and find something maybe fresh that they had to say to us or something that we might not know about.

I'm glad that you brought up Arendt. I have long been fascinated by her and I really took away a lot from that chapter. I loved her ideas about friendship. I thought that you wrote a lot about her ideas about friendship and how that is such an essential part of you framing the book of how ideas spread and people grow. She had a number of fascinating friendships in her life that you wrote about that really illustrate a lot of how she approaches the world.

Hannah was the first chapter I wrote, even though it's not the first chapter in the book.

That makes sense.

I've always been very interested in her life. I feel like the ideas are somewhat abstract in that chapter, so I want to make sure people were really locked into the framing before they got to her. But she's just, a lot of people know of her mainly as the person who wrote about the banality of evil and totalitarianism, which is absolutely true. She did. That's very important. But actually if you dig into her work, she's much more obsessed with friendship than almost anything else. For her, friendship is the basis of good politics. It's the basis of basically our humanity and how we encounter the world and how we understand the world.

She thought a lot about love and friendship, versus a general care for the world, all of which you can hear echoes of Heidegger in. Sometimes she's directly confronting Heidegger, and this was, of course, very interesting, because she was Heidegger's student. When she was his student, she had an affair with him for a few years. And then when that ended, she still fought her whole life to maintain a friendship with him, which sounds very much, from what I read, that it was not an easy thing to do.

For one thing, he was literally a Nazi and she had to flee because she was Jewish and settled in New York after that. So that's one thing. And then also he's just a prickly weird guy and full of himself. But she saw something there that was, for her, worth bouncing her own thought off of, and friendship was the way to do that. She really worked hard to maintain that, but really friendship was a foundational principle for her. The story of her life is a story of key friends.

One of them is someone who I really love and have read a lot of her work, and a lot of biographies of which is the American writer Mary McCarthy. They met each other a few years after Hannah arrived in the U.S. They saw, I think, themselves in one another and were unsure of the other person because of that. They had a famous fight, a falling out basically at a party, and then they ignored each other for three years. Then eventually just decided literally on a subway platform one night to be friends, and for the rest of Hannah's life they were very close friends. They exchanged letters all the time. They were constantly pouring out their hearts to one another. Their letters have been collected and they really meant a lot to one another.

But generally, I think the idea that friendship is a place where we hash out our individual selves, and we come to understand ourselves in the presence of people who are different from us because they're not us, is very important to her thought. I think that, I hope that that's what the book provides as well, is that in seeing the contours of someone else's life, we start to understand our own lives better.

Straightforwardly, you write about how the book is for uncertain times. I know you wrote it during the pandemic, but obviously, uncertain times have not necessarily subsided.

No.

So I suppose, what's something that you've taken away from it that still sticks with you?

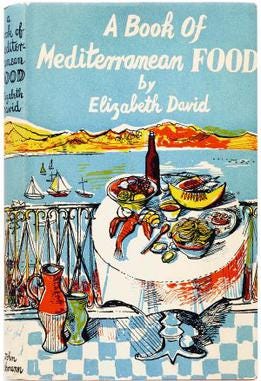

The chapter I think about most often is the one on Elizabeth David, who was a very prominent British food writer. Her books are being currently republished by New York Review Books, so you can find them, and they're about Mediterranean food, she wrote one on ice treats, frozen foods, basically. But what was interesting about her is that she wrote her first book on Mediterranean food while in the midst of really dire circumstances. She had ridden out the war in Italy and then in Egypt, and eventually she was in India for a while and she came back to England for health reasons.

And it was right after the war, and it was in the middle of austerity, and it was winter in England, which is just miserable, and there wasn't enough fuel in London. So she left London and went to this town nearby where there was fuel, but the food was just not great. It certainly wasn't Italy or Egypt, right? There was rationing. It was British food to begin with, which at the time was really, really dire. So it was gristly meat and disgusting leftover pieces put together to try to resemble something new, and she's depressed by this. And she goes out, walks every day, because there's basically nothing else to do, just trying to figure out like what on earth is going on and why am I in this gray, horrible place when I used to be in a place full of sunshine and fresh vegetables and things like that?

So she sat down to write and she says it was her dirty words, was her phrase for it. She started almost fantasizing by writing a cookbook about the foods that she was familiar with in the Mediterranean. If you read it, it reads like a straightforward guide to foods from Mediterranean regions, whether it's different kinds of soups or preparations of meat, or like how to make a gazpacho, that kind of thing. But for her, it was a way of trying to recapture these memories. And they're memories that she has no way of fulfilling. You couldn't even get really tomatoes at the time in England at any point. It just wasn't something people ate. Food from Southern Europe was viewed with suspicion by a lot of English cooks. Garlic and olive oil and things like that weren't really things that you could find in the country at the time.

But her writing was so evocative that she created the expectation that this is a good thing, and is in part responsible for your average English home cook adopting some of these items. Of course, you can find garlic and olive oil anywhere in Britain today on a regular grocery shelf. It was her imagining of better times and hoping for them, and like audacity in writing about them and talking about them, that made that actually come into fruition.

And there are many examples in the book of women who do that. The activist, Ella Baker, was really set on living as if she was living in the world that she believes should exist, a world of equality where Black women would have the same rights as anyone else. In so doing, she helped to create the expectation that that's the world we ought to live in.

I found that this really spoke to me as I was writing it in January 2021. Lots of foods aren't available, and the memory of early pandemic days is very clear, and it's pre-vaccine and everything is just super uncertain and dark, and writing about Elizabeth David really helped me capture a little bit of her spirit.

The book is called Salty: Lessons on Eating, Drinking, and Living from Revolutionary Women. Where can folks find it?

You can find it anywhere you would buy a book. I would recommend ordering through your local independent bookstore or using Bookshop online, but you can certainly get it from any of the big guys, too. It's actually, if I'm bragging on it, it's illustrated. It has really nice illustrations. And it's a little hardcover book, so it makes a really good gift. The way it's set up as distinct essays, I think actually makes it really good for, if you want to pick up something to bring on vacation, you can just read a chapter and then read the next chapter the next day. And it will read really well that way.

There's also an audiobook, which I did not read, but I think that would be a delightful way to engage with the book if that's your jam or if you just want to have some walking around stuff. But generally, I hope that people read it and use it as a way to discover the works of all of these super fascinating women.

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Thank you so much for becoming a paid subscriber!

Send links to me on Twitter at @WaltHickey or email me with numbers, tips, or feedback at walt@numlock.news.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Numlock News to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.