Numlock Sunday: Brendan Borrell on Power Soak

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition.

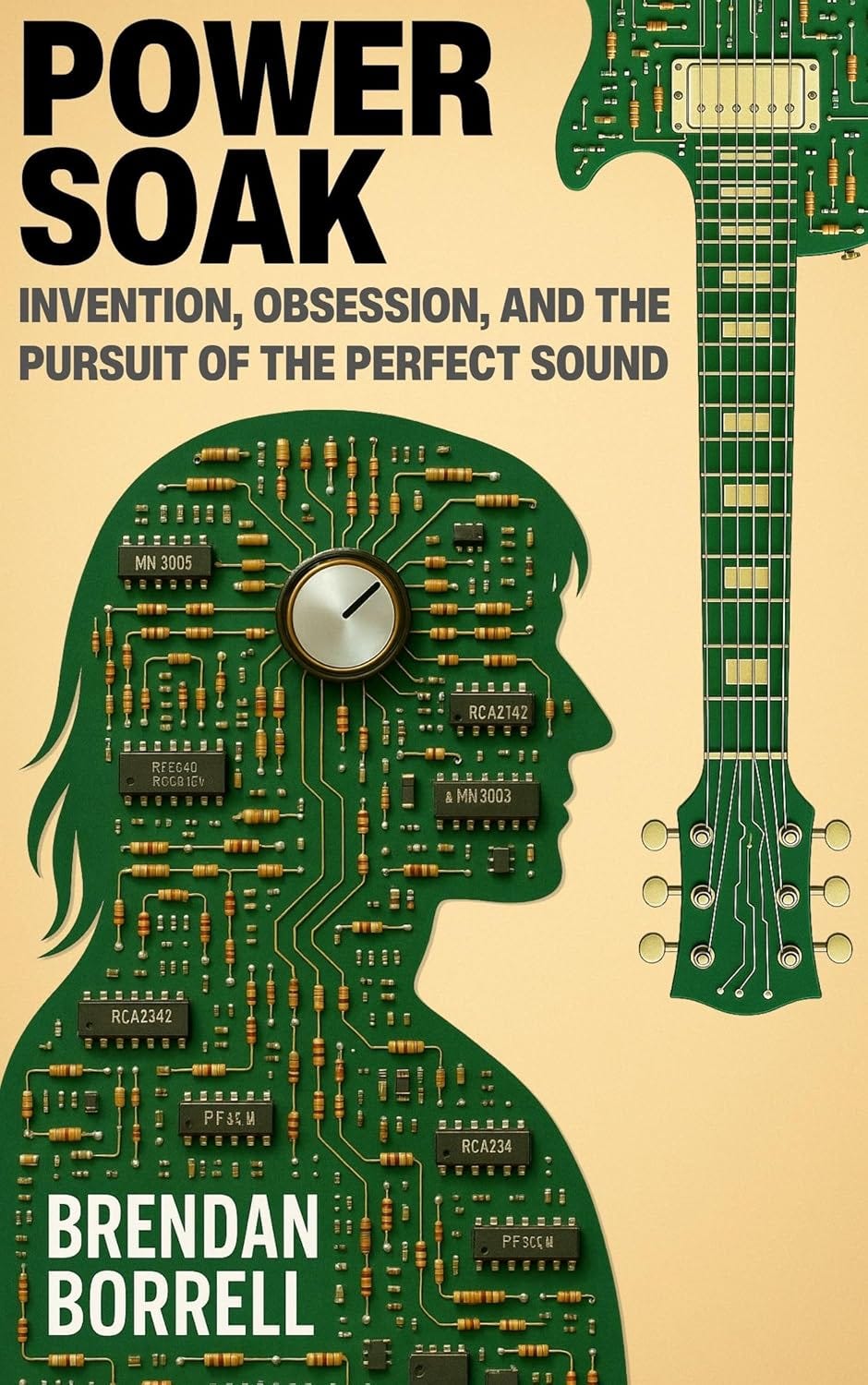

This week, I spoke to Brendan Borrell, who has written many things that have appeared in Numlock over the years in his time contributing to Hakai Magazine. Borrell is out with a delightful new book that dives into a fascinating era in the history of rock and roll called Power Soak: Invention, Obsession, and the Pursuit of the Perfect Sound.

The book dives into the troubled and genre-bending history of the band Boston, the web of vexing studio contracts that diverted their creative energies into the courtroom, the third album that seemingly could never come, and the technological breakthrough that turned the tide of chief songwriter Tom Scholz’s fortunes. It’s a great read!

The book can be found wherever books are sold.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Brendan, thank you so much for coming back on.

Thanks for having me.

Readers of Numlock might know you from your bylines over at Hakai. We are big fans of your work in general. You are out with a really cool new book. It is called Power Soak. It is a music history book that looks specifically at the band Boston.I devoured it, I think I read it in a single sitting because it was just such a really fascinating cultural, creative, legal, business story all wrapped up in one. How would you describe your interest in this story and how you came around to it?

Well, you described it pretty well. That is what drew me to the story. I’m always looking to get into these complex new worlds that have a propulsive narrative. In this case, I knew nothing about Boston. Obviously, I was vaguely familiar with the song “More Than a Feeling.” Then a friend of mine said, “Hey, they were in this huge legal battle back in the ’80s.” I started digging into it, and I realized nobody had really done the long-form version of it. And it just really resonated with me.

The music industry in the ’80s is famous for having rather large personalities. It was crazy to read a story where Irving Azov and David Geffen were present, but not even the biggest personalities in it.

Yeah, absolutely. Walter Yednikoff was the big man back in those days. Man, that guy was volatile.

Where did they come to this thing; it seems like there were a couple of contracts that broke rather badly for them.

The founder of Boston is a guy named Tom Scholz. He was this MIT-trained engineer who spent about six years working on demo tapes that would ultimately become Boston’s first album. He was just sending them out blindly and was desperate to get some buy-in from one of the major labels. Eventually, he ends up with this manager who had been key in making the Eagles a hit, along with Fleetwood Mac. Tom signed this contract with him, which turned out to be a really, really terrible deal. He didn’t discover this until years later.

Tom’s manager only had to pay Tom for every three out of four albums sold. He could discount that further by another 10%. If the record company that he sold the record to escalated his royalties, the manager did not have to pass that on to Tom. There were just all kinds of crazy little details in this contract that made it terrible.

Then there’s the recording industry contract. The manager is the in-between, but then the recording industry contract said that Tom basically had to deliver an album every six months, which, for some musicians, might be acceptable. But Tom was an absolute perfectionist. There was no way he was going to pull that off. Year by year, the pressure escalates. And that’s what sets up the story.

There’s always a transition in the story where people who had been closely working together in a band and tightly working together at a label, whether it was a label president or the hit band. Again, Boston truly was big back then. There’s a moment where all that starts to disintegrate, and it disintegrates, it seems, very, very quickly.

Absolutely. I would say that Boston had about two fantastic years. The first album came out in 1976. It was the biggest debut album of all time in history. For CBS Records, which was the biggest label in the country, it was their most profitable group. I mean, so they were enormous. They have a full year of touring, going from 1977 into 78. It was after their next album was released in 78 that everything fell apart. The band essentially (for the public) vanished for about eight years.

There are a couple of interesting things going on, one of which is that there are some internal band problems. At one point, I believe, there’s a $50,000 ad in the back of Rolling Stone for a singer who sounds like their singer.

That’s one of my favorite little details that I pulled up. That is an exclusive from this book. I’d seen a hint of it somewhere. It had been very briefly published, but there were no names attached. I found I had a copy of a deposition where Tom Scholz talks about it. He names the guy, and I tracked this guy down and learned his entire story. Tom Scholz is a very geeky guy. He’s not great at relating to people. His actual words were, “I needed to find somebody with the ‘identical vocal sound’ as my lead singer, who was basically departing the band at that point. He had this view of the members of the band as though they were just replaceable cogs in the machine. And I think that was pretty hurtful to them.

Once CBS starts bringing down the full faith and power of the Columbia Broadcasting System, it seems that the legal situation disintegrates very quickly.

Absolutely, yeah. Just to give you a little background, there are about two or three pages about this conflict in a couple of other books. Tom and CBS were at odds with each other the whole time. It turns out, when I dug into the record, that Tom actually had a pretty close relationship with Walter Yetnikoff, the head of CBS, who’s this volatile character I mentioned. He’s just the complete opposite of Tom. He’s just this blowhard lawyer snorting coke. He basically wanders into the office at, like, 10 or 11 a.m. and has a screwdriver to start his day.

But he and Tom actually had this really good relationship with each other for a while. Walter Yetnikoff recommended his personal attorney to help sort things out with his manager. He’d call Tom up and just chit-chat on the phone, which was pretty unusual for somebody at such a high level to be talking to the artist. That was pretty fascinating. But once things went bad, they went really bad.

I really like this story, and we won’t talk about every twist because people really should buy Power Soak. It’s a very good one. But there’s one that is, frankly, directly in the title, which you alluded to. There was a record that came out in 1976, there was a record that came out in 1978 and there was not another record until 1986. While all this legal machination’s going on, while their revenues have been frozen by CBS, while their royalties have been impounded because they don’t get the third record, Schultz does an end run and pulls off something really interesting that actually recapitalizes it. Do you want to talk a little bit about the Power Soak and the Rockman?

Yeah. So Tom, when he was working for those six years recording in his basement, he was inventing all types of gadgets. He was coming up with new techniques. He would layer track upon track in a way that people had never done before, just the complexity of it all. He’s using analog tape. I mean, he would modify his tape machines. I don’t know if you remember the days when you would use a tape machine and you’d hit record, and there would be like a second before it actually recorded. That made it very difficult to do super-precise things. So he would, like, modify the the $5,000 tape recorder he had so he could record instantly and come in and out of the track.

He also made gear, like the Power Soak, which, at the time this was classic rock. You want that big, distorted sound that was basically pioneered in the late ’60s and early ’70s. It comes from turning up the amplifier and getting this resonance in the tube amps. But the problem is, if you’re actually practicing in your basement, then you need to have that all the way up. If you turn it down, you lose that distortion.

Tom, what he did was put a giant resistor in a box, and he called it the Power Soak. Basically, the amplifier was maxed out, but the sound that came out of the speaker was much lower. Believe it or not, it did not exist until he created this thing. He patents it in ’79. He had a prototype for a while, but decided to put it on the market in 1980 or so at a pretty small scale. And this is just when the conflict’s heating up.

By then, he had all these other ideas for gadgets. He goes on to found this company called Scholz’s Research and Development that produces an even fancier version of the Power Soak, which basically simulates the distortion sound in a Walkman-sized box. That was called the Rockman. And this stuff takes off. All these other musicians pick it up. Def Leppard’s album, Hysteria, every track on that album that I heard used the Rockman. The Cars, who were another Boston band, were using it. There are all these incredible guitar players who even vouched for it. So, yeah, it was pretty incredible. Even though some people think, “Oh, yeah, Boston’s a one-hit wonder more than a feeling, maybe a few other songs,” they had this enormous impact through the ‘80s. They were the sound of 80s rock.

It’s just such a great story. There are a lot of very fun twists in this. The legal machinations are very fascinating to follow. The moment that this thing goes from being not just a legal fight, but a very clearly personal battle between some very large personalities. It’s all really, really good stuff. I highly recommend it. Obviously, this is a story about creative power, technology, and corporate greed intersecting. This is not the last time that this happened in the music industry, right? This does feel like a very pertinent story. Even towards the end, you allude to some of the work that Taylor Swift did in reclaiming her masters. Why is this story still relevant today in your view?

Yeah, I mean, absolutely. Scholz’s battle really created a moment when a number of artists started trying to use these same methods to break their contracts. Scholz’s lawyer, this guy Don Engel.

He was fascinating.

He was fascinating. He’s a big character, and he discovered this loophole in California law that basically said you can only have a contract for seven years. The way the record industry was doing things, it would say, “Hey, you need to give us this many albums.” If you’re too late on an album, we’ll just extend your contract for another year and another year. Scholz had eight albums that were due. Anyways, once Scholz started to break himself free, other artists saw an opening. Don Engel just became a huge name in the 90s and 2000s. He was known as Busta Contract.

Prince, part of the reason he changed his name was to get out of his contract. The funny thing about Prince is that he wanted to release his albums faster than the record company wanted to release them because he was so prolific. And then Taylor Swift ended up buying back her masters. There are just so many stories like this because these contracts the deck is stacked against the artists. The record companies will say it’s because we invest so much in developing, most of our artists don’t actually ever make back the money and so on and so forth. But it definitely can be pretty hurtful for the person’s career. In Tom’s case, it was just egregious. I mean, he was getting a fraction of what everybody around him was getting.

Yeah. So, again, the book is called Power Soak. Where can folks find it? Where can folks find you?

Yeah, Power Soak about Tom Scholz and his long fight against CBS Records. It’s available on a bunch of online bookstores: Amazon, Apple, Barnes & Noble. And I am at brendanborrell.com or find me on Twitter.

Awesome. Well, hey, thanks for coming on.

Alright, thanks for having me.

Edited by Crystal Wang

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Thank you so much for becoming a paid subscriber!

Send links to me on Twitter at @WaltHickey or email me with numbers, tips or feedback at walt@numlock.news.