Numlock Sunday: Bryan Caplan on open borders

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition. Each week, I'll sit down with an author or a writer behind one of the stories covered in a previous weekday edition for a casual conversation about what they wrote.

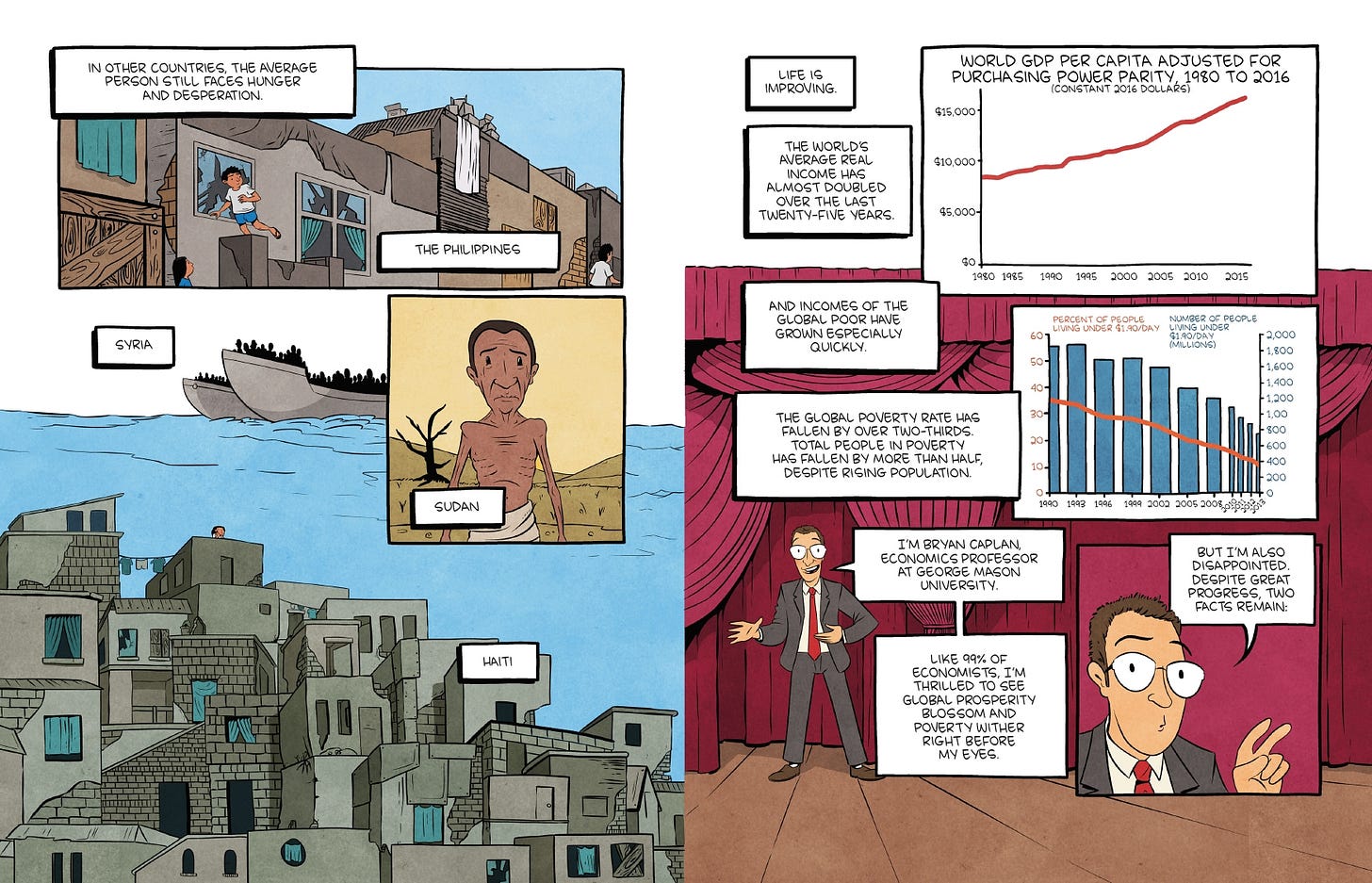

This week, I spoke to Bryan Caplan, the author of the new book Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration which was created with Zach Weinersmith, an artist that longtime Numlock Sunday readers will remember I interviewed about a year ago.

Bryan and Zach are out with a book that dissects the complex issue of immigration and ends up taking the strong view in favor of open borders. The book’s thought-provoking, deeply researched and makes compelling arguments in favor of the ideas at its core.

Open Borders is available on Amazon, Barnes and Noble really wherever books are sold now. You can find Bryan at his website and blog and Zack at Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Walt Hickey: Can you tell what got you interested in the topic of immigration in the first place?

Bryan Caplan: When I was an undergraduate, I was just learning about different types of regulation and how they work, and to me immigration regulation seemed to be something where the rationale is at odds with what people would normally advocate. Say you have a case of a very poor person who just wants to come to the U.S. and get a job. But it's illegal! It's something where it increases economic efficiency, and reduces inequality, and reduces poverty, and yet it's illegal. That's what got it on my radar.

I started thinking about it a lot more when I started blogging around 2000, and I started reading research about how not only do the laws do all that wrong, but actually the harm seems to be enormous when you measure it, just because there's such a large number of people affected and the deprivation of opportunity is so severe. It's really just a situation where you can take a worker from Haiti and move them into the United States and overnight they can easily produce ten times as much. There are billions of people on earth and when you do the math, it really does seem like these regulations are the most harmful regulations that exist on earth.

What are the economic gains?

The book does argue full deregulation. I talk about other, more moderate proposals as well, but the main idea is that these are regulations that are designed to stop something which is good, namely, people moving from unproductive parts of the world to productive parts where they can not only enjoy the benefits of their talents but they can share their talents with the world.

In the book I had this thought experiment where you've got a million farmers in Antarctica. What do they contribute to the world economy there? You have nothing. They're just eeking out an existence, and they’ve got nothing to sell. But if you let them move to a country with more fertile conditions for farming, not only are they better, but they also wind up enriching the world, because they aren't going to eat all the extra food they grow, they're going to sell it and it's going to feed the rest of us. That's the heart of the book, these are regulations that are designed to stop people from doing something that we should really be happy to have them doing, which is moving to a place where they could contribute more to the world and solve their own problems and improve their own lives by helping the rest of the world.

Why did you pick the medium of graphic nonfiction?

Part of the answer is just that I love the medium, I'm just a big graphic novel fan, I've been wanting to do one for really long time. I have an enormous collection. But also in the process of reading them, I just saw that there were some great authors that were really combining words and pictures to express themselves and make their point more effectively than you can do with words alone. There's this great five-volume series by Larry Gonick, called The Cartoon History of the Universe, which if I were in control of national textbook selection, those would be the history textbooks I would use for the kids in the country. They're just better books than regular textbooks. There's so much better and so much more informative, so much more engaging. You can be extremely accurate and at the same time much more entertaining and memorable if you do it this way.

When I saw that there were other authors that were using this graphic format to communicate more effectively, it really made me want to try my hand and do something as well. Also, for me, a lot of my favorite arguments are thought experiments, like that one about a million farmers in Antarctica, and I realized that thought experiments really are better drawn rather than merely described. I wanted to really bring the thought experiments to life and make people appreciate them on a deeper level. I think I was able to do that in this book with the great help of the incredible artistry of Zach Weinersmith.

How'd you get linked up with Zach?

There's a story there. I had a mental list of the artists I thought would be best for the book and he was my number one choice. But I didn't know him! So I just friended him on Facebook, and he friended me back. And then I waited a few weeks — very strategically, I didn't want to immediately start bothering him as soon as he accepted my friend request — then after a few weeks I sent him a note saying, "you know, I really like your work, I have a project that I just want to talk to you about. Do you have some time?" And he said yes, and so I went and told him about the idea, and then he said he'd think about it and then he said, no, I’m just gonna have to pass on this.

And I was disappointed about it but figured you can't expect to get your first choice in the world. A few days later he wrote me back and said, "I changed my mind, I want to do it!" I just completely lucked out there, because he's a great collaborator, a 100 percent positive attitude, taught me so many new skills, he held my hand and really gave me a lot of help for like what kinds of drawings will work, if you're doing a closeup what kind of sized panel do you need? I did do the storyboards for the first draft myself, but then he just gave me so much useful advice panel by panel. It was the best collaboration of my life.

Are there any stats that you found in the course of reporting the book that you found particularly eye-popping?

The biggest one is people have tried to estimate how much richer would the world be under open borders? It's very far from where we are, so it's just an estimate, but a typical estimate is something like doubling the production of the world, doubling the wealth of mankind just by going and lifting the very destructive regulations. When you understand the math it's not hard to see where this big number's coming from, because the regulations lead to a large reduction in productivity. Someone really can come from Haiti and the day they arrive produce ten times what they were producing back in Haiti because the U.S. is so much more fruitful for production than Haiti. Then when you realize how many millions of people are affected, you take a large gain and multiply that by hundreds of millions of people and if you put that all together you get an enormous hit to the production of the world from the regulations that we have and a huge potential for gain if we would just go and tear down those regulations.

What do you think is one of the more unexpected things you found.

The section of the book that I fought the hardest to keep in, because it was most controversial, is there are a lot of people — mostly in the dark reaches of the internet — saying, they "don't want to let in immigrants from poor countries, because they have low IQs and they're going to ruin our country with their low intelligence." Now this is not a view that many people want to publicly stick their neck out and say, and yet there are a lot of people I found who actually say it anonymously, or will say it off the record.

Rather than just browbeat them into submission, I wanted to really take the argument seriously to see how solid it really is.

First of all, the actual evidence that reducing average IQ in a country will cause some kind of great harm, that doesn't seem to be true. There's such a big gain in moving people from poor countries to rich countries, that whatever else might be going on is just overwhelmed by those enormous gains. But the most fundamental thing that I discovered from going in and reading about the effects of international adoption is that out of all the things that we know on earth about how to raise human intelligence, probably the single most effective thing is to take a kid from a third-world orphanage when they're a baby and move them to the first world. If people are using low IQ as a reason to prevent immigration, a lot of the reasons why people's IQs are lower in poor countries is because they weren't allowed to immigrate.

If you have an idea about how bad conditions are in a third-world orphanage, the degree of poor nutrition and sanitation and neglect, then just going and moving someone into much better circumstances, you can really measure an enormous gain there. The actual benefit for them of just letting them leave is enormous. This is really well documented for things like height and weight, where if they stayed home at the orphanage they'd be short and really malnourished. But then there's also very good evidence on cognitive elements. As long as you get them at a young age, moving to a rich country does work wonders for people.

That's something that seems lost on some of the folks who are, um, really ardent when it comes to immigration issues.

I feel like I've got a lot of credibility on this because I have another book talking about how in rich countries, we tend to underrate genetics but when you're talking about international adoption, that's a whole different story because the parental deprivation you're talking about is very different from what you would see here. In rich countries, the poor are more likely to be obese than the rich. But that's not true in poor countries at all.

You have a forthcoming project coming up about who is to blame for poverty. What attracts you to these issues?

A lot of what gets me interested is when there's an important topic where I just think that there's a correct view that almost no one wants to defend, it either gets neglected or is just so unpopular that no one wants to stick their neck out. It's when I find those topics, I'm motivated to write a book. I never have and never will write a book to say "the sky is blue, here's why." There's lots of other people writing that book. I don't need to write it.

On the topic of poverty, an enormous amount has been written about it, and yet there are many big points that are very well documented and yet just don't get much attention. A big part of that poverty book is going back to the question of immigration again and saying, look, here's a way where the world's poorest people, if you just give them a piece of paper saying that they're allowed to come, they can make a vastly better life for themselves. And yet the government doesn't want to hand out those pieces of paper. Why? Why is it that people are so eager to prevent someone coming from Haiti or Mexico or Cambodia to the U.S., and enriching their lives and enriching the lives of the rest of society?

A big part of my work on poverty is I think that people have unjustly cast aside the difference between the deserving and the undeserving poor. To me, it's hard to think of anyone more deserving than a poor immigrant, someone who's born in difficult conditions and then pulled themselves together and want to come and work their way out by their own bootstraps. Get out of their way and let them get a job. To me, that's almost the definition of a highly deserving person and yet they're the people that the law persecutes so strongly.

This isn't your first book, can you tell us a little bit about what other work that you've gotten up to?

I'm an economics professor, all my other books are in traditional books in an academic style. I always try to reach a broader audience. I put a lot of effort into polishing the writing and just making it, not a boring book written by professor, but I've got two books with Princeton University Press.

There's one called The Myth of the Rational Voter: Why Democracies Choose Bad Policies. That's one where I try to explain the possible why governments by and for the people seem to do so many bad things. What I say in the book is people are confused in a lot of cases and they vote emotionally. So a lot of bad stuff wins by popular demand.

I've got another book with Princeton called The Case Against Education: Why the education system is a waste of time and money and that's the book where I try to answer the question: why is it that so much of what you learned at school seems so irrelevant to the real world, and yet employers care so much about your credentials? My story is that employers really don't care that much about what you've learned, rather what they're looking for is to see that you've jumped through a bunch of hoops, which certifies you as being a smart, hardworking, conformist sheep. And then the book really just tries to go through all the evidence for that, and it really tries to win the skeptics over but also you're trying to figure out what does this mean for education policy? It really comes up with this contrarian view that spending more on education is really counterproductive, because the more education people have the more people need to have to be a viable job candidate.

I got one other book with Basic Books and it's called Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids: Why Being a Great Parent is Less Work and More Fun Than You Think. This is a book where it's about the economics of family, but it's also about human genetics, basically it begins with a lot of evidence that people underrate genetics and overrate family environment, and then says that this explains why people have this not fun, high effort, stressful parenting style of trying to be a helicopter parent, control what your kids are doing and make them do a whole bunch of activities they don't want to do. That in turn explains a lot of why people are so reluctant to have kids today, because we have needlessly turned parenting into this chore. It's one where I try to combine what's going on in different areas of psychology, sociology, medicine, and understanding why human beings turn out the way they do, and then use that to rethink not only the way people raise their kids, but also the number of kids it makes sense to have.

Where can people find your work?

You can find me at my website and my blog and all my books are for sale on Amazon. As for Zach, if you like these comics, go to Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal.

The book is called Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration, you can get it at Amazon, Barnes and Noble really wherever books are sold now. Borders, Barnes and Noble, it's going to be everywhere. Actually, take away Borders, it's not going to be at Borders because Borders is bankrupt.

Yeah, it is so out of character for you to encourage people to go to Borders.

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Thank you so much for becoming a paid subscriber!

Send links to me on Twitter at @WaltHickey or email me with numbers, tips, or feedback at walt@numlock.news.

OMG, Walt, thanks so much for bringing Bryan Caplan to our attention!!! I have to say, I've learned a LOT from your newsletter, but this is PEAK learning! I am looking forward to putting Bryan's books on my Christmas list and checking out more of Zach's work. Again, many thanks! <3

Great thoughts...esp. about education!