Numlock Sunday: Chris Dalla Riva introduces Uncharted Territory

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition.

This week, a fun special edition everyone gets to read. Good friend of Numlock Chris Dalla Riva, the data and music mind behind the newsletter Can’t Get Much Higher, just announced preorders for his new book that’s out this fall, Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves.

A huge interest of mine is the intersection of pop culture and data, and a topic I remain endlessly fascinated by is the phenomenal work done by folks like Chris in the exciting area of music data journalism.

I’ve been looking forward to this book for ages, and while he’ll definitely be back when the book properly launches in November preorders are really important for the launch of a book and now that those are open I wanted to have him on to talk about what’s in store.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Chris, thanks so much for coming back on. You are one of my favorite people to have on this thing, so it is always a delight to get you back.

Well, it’s one of my favorite places to be, so happy to be back.

You were on somewhat recently, and I usually try to space these out a little bit more, at least, but in this case, it was just too exciting to pass up. You just announced last week that you are publishing a book coming out this fall and that pre-order is available. I have read this book; it is really, really good and exciting. What’s the book, where it’s coming from and what might people find interesting about it if they find themselves pre-ordering this thing?

Yeah, totally. So, the book is called Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us About the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. The short description I always give people is that it’s a data-driven history of popular music. It covers from 1958 to the beginning of 2025. So pretty close till today, or as close as we can get till today, and still adhere to a publishing schedule. The idea is that I spent a couple of years listening to every Billboard Hot 100 number one hit. That chart started in 1958 and still exists today, and along the way, I would track a ton of information about each song in the spreadsheet. Then I used that information to tell a novel history of popular music.

You see a lot of the same characters that you would expect in a story like this: The Beatles, The Bee Gees, Phil Collins, Drake, all those stars. But it’s told with numbers and data that hopefully make you think about the music in a different way. It also allows us to investigate things that people often say about popular music and see if those things are true. We can’t quantify everything, but there are certain things that we can quantify.

Yeah, the quantification part is so fun. You glanced over this, but you personally had this years-long project where you were listening to and consuming every single song in the top 100. I guess what even got you on that point?

I’ve always played in bands, I’m a musician, I like writing songs. I was living in Boston at the time, I was working a job I didn’t really like, and I was just looking for some way to engage the more creative side of my mind. I don’t remember exactly how I came upon it, but I was like, “Oh, I’m gonna listen to every number one song.” I was like, “I’ll do one a day.” I would usually play along on my guitar, figure out what was going on.

Then one of my friends was like, “Oh, I’ll do it with you,” and we used to rate the songs. I would log the ratings, and that spreadsheet of ratings slowly blew up into this humongous spreadsheet (when the book comes out, I’ll make it available online) that tracks an absurd amount of information about each of these number one hits. But really, it began as just something to do to challenge the musical part of my mind. When a friend started doing it with me, you have a little bit more incentive to keep going; we’d text about the songs, and then it just turned into this other thing.

What hits the top of the Billboard chart is not necessarily the best-known songs; there’s a lot of stuff in the book about songs that were either idiosyncratic or the biggest hits that never got to No. 1. What about the Billboard chart in particular got you interested in seeing what would hit the top?

I chose Billboard because it has existed for decades upon decades. The chart has changed dramatically over the years, where it’s not really the same thing as it was decades ago (because now it’s tracking streams instead of sales), but there is some continuity. You could go from the late ’50s all the way up until today, which is great. There have been other charts over the years, but most of them go bankrupt or are no longer published, so this at least allowed for some continuity.

The thing I really like about the Billboard chart is that it’s aggregated once per week, and its goal is to find the most popular song in that given week. To your point, within a given week, a horrible song can be very popular. Within a given week, you could have a very, very good, very popular song come out, and there just happens to be one random song that is a little bit more popular and doesn’t make it to No. 1. A good example of this: Bruce Springsteen never had a number one hit as an artist. The closest he got was No.2 with “Dancing in the Dark.” The reason he didn’t get to number one was because Prince had “When Doves Cry” out at the same time, so it’s just bad luck on Bruce’s part.

However, because of that, you end up getting a more accurate picture of what popular music is like in each decade. If you look at other lists of the greatest albums or the greatest songs of all time, they don’t include the things that are bad or the things that people don’t listen to anymore. But those things that people don’t listen to anymore are just as important to the history of popular music as the songs and albums that have been handed down over the decades as masterpieces.

Because the Charts are aggregated once per week over decades upon decades, you get a good sample of the good and the bad and the weird and the eternal all smashed together, which I think is a more accurate picture of how people actually listen to music.

That’s really fun. I like that a lot. I think we do have this issue with the canon. There are so many debates over what is the canonical list of songs. These debates can turn over very, very quickly. “By chance, what was the most popular song in history for a week, in a week?” is a fun angle. What are some things that you’ve done that articulate what this book is going to be about?

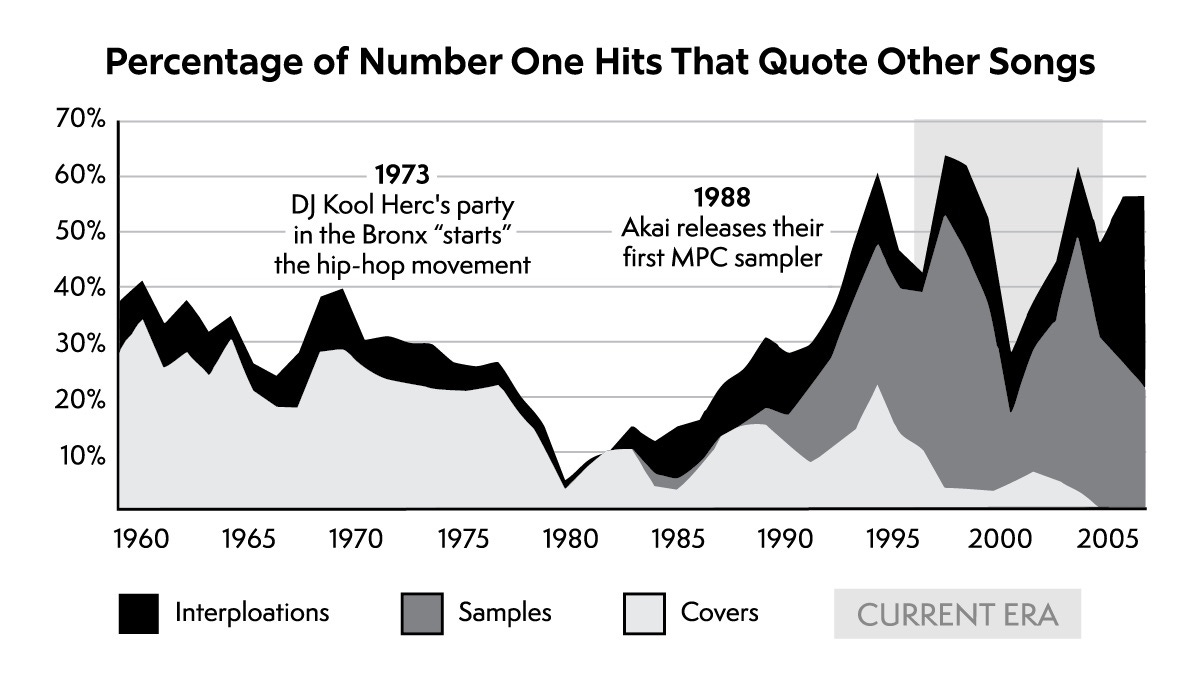

I think one of the broad things that comes up again and again is how often popular art, and specifically popular music in this case, is downstream of technology. This is something I track incidentally throughout the entire book. A classic example is why is the pop song, your typical pop song, like three to three and a half minutes? You go and look back, and you’re like, “Oh, vinyl singles or shellac singles could only hold that much music without losing sound fidelity.” So you don’t see popular songs become longer, “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Hey Jude,” until the late ’60s, when that technology improved.

To me, that’s very interesting because you’re just looking at something that seems very basic, such as the length of a song. But what the average length of a pop song reflects is something much larger about how people record music and how people listen to that music. And throughout the book, you see that over the decades. I mean, vinyl is one particular thing, but you can also talk about how musical output is downstream of radio programming formats and cable television and the proliferation of MTV and eventually the Internet and Spotify — in this day and age, music generated with artificial intelligence. I think it's a way people don’t often think about the creative processes: you’re working within constraints that are often dictated by technology.

That’s interesting. What other constraints have there been?

I think another good example is the microphone.

You really see the rise of Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby when microphone technology improves throughout the 1930s and 1940s. It allows people to record this softer, gentler croon that wasn’t possible in the early 1900s, when you had to scream into a giant horn to record your voice. Or even before that, when there was no such thing as electric amplification, and you’re on a stage and you have to just project. That Sinatra, Bing Crosby vocal style that was popular for decades is partially a byproduct of the fact that amplification, electrification and microphones happened to all improve across a 20-30 year period — from the beginning of the 1900s until they came on the scene.

I know that it’s a topic in the book, is that we have a lot of these somewhat more trite narratives of music history reflecting American history. But the Billboard charts capture just straight up demand. The history of music and its relationship to politics, society and war, it’s a lot more of a nuanced picture when you look at just literally what was leading the Billboard charts versus the one that we have.

Yeah, totally. Decades later, we know that the Vietnam War was a really bad thing. A lot of the music that survives from that era is music that condemned the war. But in 1966, for example, I think one of the most popular records of the year was called the “Ballad of the Green Berets.” It was by a guy who was a staff sergeant in the military, and this record was tremendously popular.

You wouldn’t think that a song glorifying the military and the Green Berets specifically would be popular, looking back on Vietnam all these decades later. But at the time, people’s perspectives were very different. The art that is popular reflects that, but nobody really listens to that song anymore unless you’re going to an oldie station. However, I think the fact that it was popular is important.

So, taking a step back, what do you think that this book has that would either make people really excited, or surprised, or interested in picking it up?

Yeah, so I think there are a couple of people. If you’re interested in music generally, this is going to be the book for you. It covers such a large period of time (1958 till today) that I like to joke whether you danced “The Twist” or the “Soulja Boy” at your senior prom, there’ll be something in there for you.

But also people who are more generally interested in culture and in analytics. Similar, I think, to an audience that you courted with your book is people who are interested in how we can think about culture differently and how we can quantify culture. A lot of people think that numbers are and statistics are going to destroy great pieces of art. But I think in many ways, it can illuminate things that we otherwise wouldn’t know.

Plus, this book isn’t a math textbook. I also have set it up in a way that will stoke some debate and allow you to think about what you actually enjoy about songs and what you don’t enjoy and why certain things are good and bad. So anyone with an ear, I think, is the audience for me.

We have hardcover and e-books available. Anyone interested, feel free to preorder. It will be out this November. I have been mentioning in other places that if you are a person who runs a podcast or a newsletter, I am down for almost any and all press. So feel free to reach out; I will probably respond.

Alrighty, I think that puts us in a good place. I would just simply remark that this sounds like a phenomenal Christmas gift, too.

Oh yeah, yeah, yeah. It’s a great gift for mom and dad at Christmas. Or like I said, it covers a long period of time, so get it for your brother or sister, too. Multiple copies for the whole family.

Edited by Crystal Wang

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Thank you so much for becoming a paid subscriber!

Send links to me on Twitter at @WaltHickey or email me with numbers, tips or feedback at walt@numlock.news.

Preorder ✅