Numlock Sunday: Chris DeVille on Such Great Heights and the indie rock explosion

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition.

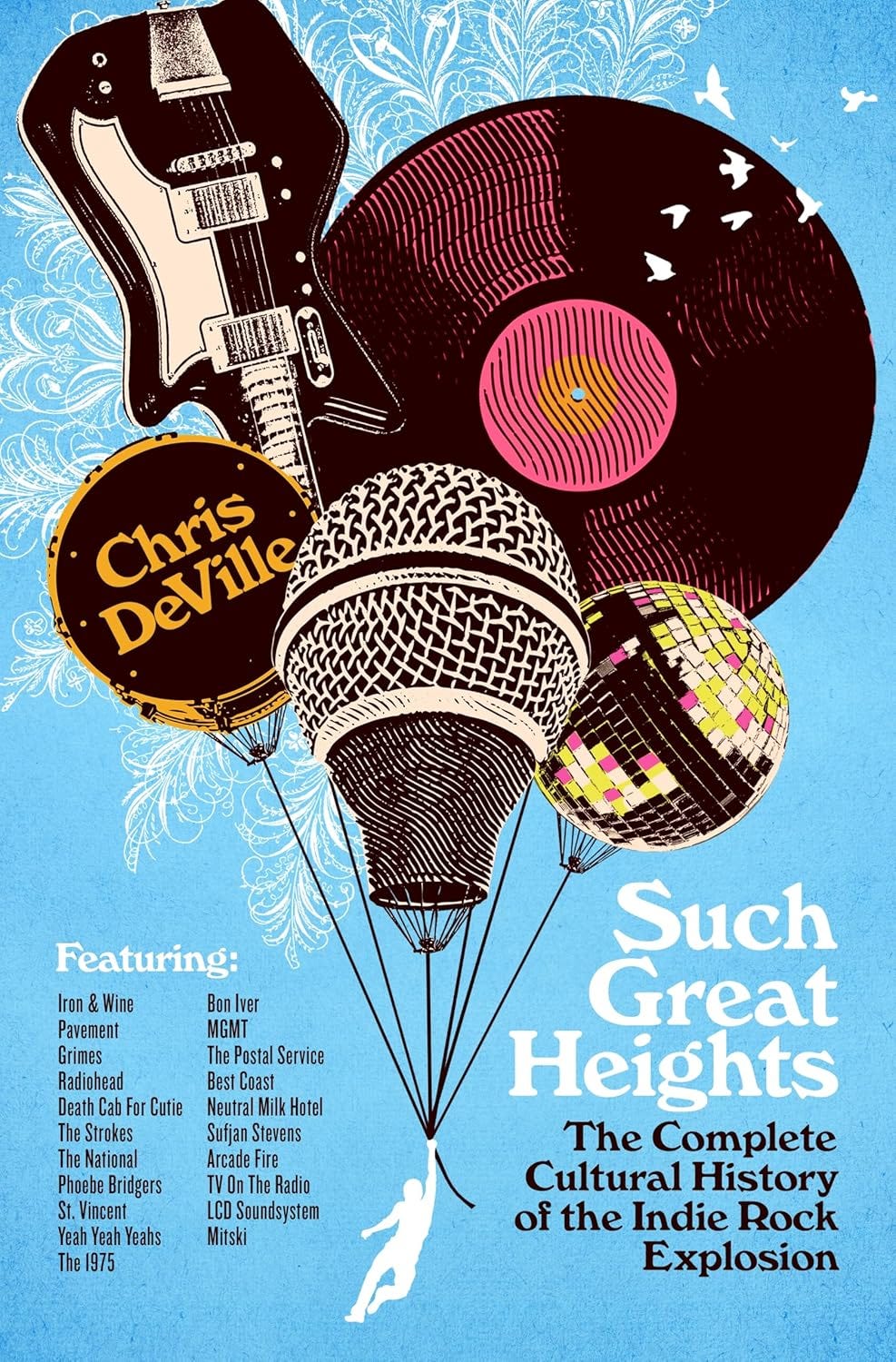

This week, I spoke to Chris DeVille, the managing editor at Stereogum and the author of the brand new book, Such Great Heights: The Complete Cultural History of the Indie Rock Explosion.

This book is exactly my jam, I loved it, it tells all about

We spoke about how “indie rock” slipperiness as a genre, how the big winners of indie rock were some of the largest corporations on the planet, and what lessons we can draw from that era to today.

Such Great Heights can be found wherever books are sold. He also has a newsletter where he reveals a bit about the background of the book, too:

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Hey, Chris, thank you so much for coming on.

You’re welcome. Thanks for having me.

You are the author of a brand new book out in stores today called Such Great Heights: The Complete Cultural History of the Indie Rock Explosion. I really love this book. This is exactly my jam.

It tells a really interesting rise and fall story about one of the most pervasive and significant cultural forces in the world today. Just backing out a little bit, what got you interested in this topic to begin with? It seems like you have a very, very long history with independent rock.

Yeah, it was a write what you know situation. I have been following indie rock basically since I was a teenager. It’s been very important to me. I’ve been writing about it professionally for a long time. I just felt like there was this story of the way it evolved and transformed. I think people who followed it understand it intuitively, but I wasn’t sure it had ever been laid out in a book.

I felt like a lot of the documentation of these cultural currents and trends took place on blogs that don’t exist anymore and message boards and social media posts and stuff that’s really ephemeral. It just felt like a story that I was equipped to tell, that I found to be very fascinating, and a convergence of a lot of different cultural factors. And it deserved to be preserved in a hard copy format.

Indie rock is, at face value, a format. It refers to the label of the producer of the music. However, as a sound, which is what a lot of the book is about, we have a very distinct cultural memory of what indie rock sounds like. It’s a very slippery genre. How did you reconcile what is and isn’t indie rock, and where do you begin and end?

Yeah, so I felt like another way to explain the concept of the book is almost just saying it’s about the way the word “indie” has been morphed and stretched almost to the point of meaninglessness. I really wanted to establish in the first chapter “what did people mean when they said indie rock 25 years ago when I first was getting into it.” We could then trace how has that meaning changed and in what ways and why over the last couple of decades and change?

It’s a slippery term. It’s a slippery concept because even back in like 1990, even before Nirvana (which Nirvana and all that stuff is really just like a preamble to the story of this book). Even before that, you had Sepido coming out with the song “Gimme Indie Rock.” There was an implication that there was an aesthetic and a genre to it. It wasn’t just about being on an independent label. It’s always been a mess.

That’s what the book endeavors to do: figure out what was it and why did I like it so much? And what were the reasons for it to blow up? And what were the reasons for it to morph into pop music, more or less? I found that there were a lot of different factors there to consider.

The book has a lot of deeply recognizable and still very significant cultural figures of our current moment — whether it’s Taylor Swift, Kanye West, Grimes. A lot of major institutional players either came from indie rock or took significant inspiration from it, or hired people who were central to it.

What are some examples of the ways that indie rock has been either co-opted by mainstream music, or just Capital in general? Apple clearly made its bones selling iPods to indie rock listeners, right? Outback Steakhouse would not have music to play during their advertisements without this music.

Yeah, Apple’s a big one.

Part of chapter five is the 2000s tech chapter. It gets into Myspace and Napster and iTunes. Apple used indie rock in the commercials, but it was really interesting that something like Jet — that’s like one of the most famous iTunes ads — is silhouettes dancing to Jet.

And I found it fascinating that Pitchfork and a lot of the tastemakers just hated Jet. But to the average viewer or listener whose brain hadn’t been poisoned by the internet or poisoned by like hipster hipster posturing, there probably was no discernible difference between Jet and Strokes and White Stripes. So it was interesting to see the less critically acclaimed version of indie catch on within the commercials.

Certainly, some of the critically acclaimed bands ended up in commercials, as well. You have Grizzly Bear and Phoenix and Vampire Weekend; those were all bands that got a lot of critical love. They also eagerly ended up in TV ads.

But when you think about this question of the mainstream co-opting indie as an aesthetic or as a concept, I felt like a natural endpoint for the story that I was telling was Taylor Swift releasing Folklore and everyone calling it her indie album, just because she worked with Aaron Dessner from The National and Bon Iver guest-starred on the album. A lot of the instrumentals on that album — Aaron Dessner has said — originally were intended for The National.

I thought that was really interesting to see: the biggest pop star in the world releases the most successful album of the year on a major label, embraced by the Grammys, embraced by every aspect of the established music industry. And it’s considered her indie album just because of the people that she worked with and the sound that she explored on it. That was when I was like, “If this is indie, then what does indie even mean?”

I guess to pose your own question back to you. If that’s indie, what does indie even mean?

Yeah, I mean, at this point, it feels more like a genre descriptor. Or even, it’s not a genre as much as it seems like a demographic descriptor. During the early 2010s, when all the indie bands were trying to become pop bands and you had the rise of the indie pop star, there was a lot of music that got shoehorned in as “indie,” but had nothing to do with the historic baseline of indie rock, as you would understand it in the ’90s.

To me, it almost came to be that indie is anything that the indie rock media and listenership took an interest in. Anything that could potentially go on stage at Pitchfork Music Festival (R.I.P.) or anything that we could cover at Stereogum, this is what’s being embraced by the indie audience.

I felt like one of my takeaways was that indie has almost come to mean a certain audience, or maybe even an array of audiences that aren’t necessarily connecting with each other. What gets played on like a SiriusXM indie station could be completely different from what gets highlighted in Bandcamp’s new picks for the best albums of this week. And, maybe the stuff that’s happening on Bandcamp is more in the underground. And yet, I think we would probably use the word indie to describe both of them.

I actually want to talk about the intersection of technology and indie music. You wrote about two specific phenomena of distribution that fundamentally changed indie.

The first was the MP3. You wrote about how it had a way of eliminating genre; you could have a burned CD that had both the pop hits as well as an indie artist that you liked right next to each other. It made indie rock very much like a peer of the pop charts. Then you later wrote about Spotify, which you wrote only works at scale. By definition, it penalizes independence, right?

How did technology flow into support and ultimately deflate a lot of what we’re talking about?

I realized at some point when I was writing the book that it was like a shadow history of the internet and online life over the last 25 years. And that was one of the ways that I felt like it would really connect with a millennial, even if they weren’t necessarily super deep in indie rock specifically.

As far as the way that indie intersected with those things, I think MP3 was huge. And the iTunes store, but even before the iTunes store, there was piracy. On the one hand, this music that didn’t necessarily fit into existing radio formats had a way to bubble up without as much gatekeeping involved. The bubbling up made it possible for a broader audience to hear some of these more indie-type songs. But on the other hand, it created a scenario where the existing indie audience suddenly had access to a much more eclectic range of music, as well. You see it being reflected in like, the year end lists, and the coverage in the blogs and Pitchfork.

Throughout the 2000s, you see more and more genre variety happening there. This was a time when it was becoming trendy not to define yourself by one certain genre, but instead to be a really eclectic listener. I think MP3 has had a lot to do with that. So as a result of that — and Myspace factored into that as well — you had a lot more hybridization happening. Music is always evolving, and genres are always getting bred together, but this really facilitated that happening a lot faster.

It also facilitated bands being discovered a lot faster. Once the MP3 blogs came into the picture, you had the race for the hot new thing. Whereas a band that would have spent a couple of album cycles slowly but surely building up an audience, they just get moved directly to the front of the line, because they get one cool song that catches fire on the MP3 blogs.

Then they build up this unsustainable hype bubble. Clap Your Hands Say Yeah is the default example of that. So, that’s the whole MP3 part of it. There’s a whole other dimension to the MP3 thing. Once iTunes was in the picture, and people were starting to pay for MP3s, that was huge for indie record labels, because they were able to make money without manufacturing product.

Something like Merge Records; I have more of a balance for Merge Records. I quoted in the book from a talk that she gave at Drexel University. She was talking about how all of a sudden, when something like Spoon would have a hit song, they would go on the OC or whatever, and they were able to sell MP3s of that. Both the label and the band would make so much more money off of it, because they didn’t have to pay for pressing up records and stuff. There’s so much from the MP3 that factored into indie rock.

But then Spotify comes along. All the streaming services, but certainly Spotify is the dominant force. The payout for streaming is way, way less than the payout for downloading an album on iTunes. Bands were losing out on the album sales already, but it was being replaced for a while by sales on iTunes. When streaming comes along, album sales really start to tank, because people are just going to pay for their monthly streaming subscription instead. And only the most devout fans are still buying the record, either because they still prefer vinyl or because they want to support the artist.

Streaming really has an impact on the media ecosystem, too, because people feel like, “What’s the point of an album review? I can check out all this music myself.” Then streaming services start algorithmically recommending music to you as well, taking over the role of the music critic. A lot of the infrastructure that made the pipeline that a lot of these indie bands rode to stardom in the 2000s collapsed in the 2010s.

On top of that, if we’re talking about an artist that doesn’t have hype behind them, whatever meager profit they might be able to make from album sales, they’re not going to get anything off of streaming. Your song has to be streamed a thousand times on Spotify in order for them to pay out anything to you. There are so many ways that Spotify is a game changer for the music industry, as of like 10 years ago. But it really does benefit the one percent.

Even just putting stuff on the playlist placement, it was like the rise of the Spotify playlist as a tastemaking entity. It’s like a return to radio. And there’s certainly payola involved in all of that, just like there used to be on the radio. Who knows what various things are going on behind the scenes in terms of what gets exposure on Spotify’s front page? I shouldn’t speak as though I know all the details of some dirty deeds.

It feels like the internet used to feel like a wide-open frontier, when indie rock was blowing up. Now, it feels a lot more walled-in and clean-lined — at least the part of the internet that’s geared around the industry.

Yeah, I think indie rock has made a lot of people a lot of money, and often it isn’t necessarily the people who make indie rock. I think that was a very fascinating outcome of the book. There was a shocking anecdote in there that you had about Volkswagen wanting to put a Beach House song in a commercial, and then Beach House turning them down. Do you want to talk a little bit about that?

Yeah, that was an interesting story. Beach House are the masters of vibey, psychedelic, shoegazy, mood music. They’re the perfect indie band for the last 10 years or so. When people moved into more of a streaming mindset, a lot of mood music overtook the more visceral music. I remember reading some review of their music that described them as the perfect band for the vape pen era as well. They’ve been a very important indie band, and of course, when they blew up, people who make commercials wanted to have their sound in the ads.

There was an instance where Volkswagen approached Beach House multiple times over the use of a particular song. And Beach House said no repeatedly, because they didn’t like the concept of the ad. They’re not against the idea of selling their song to a commercial. They’ve done other commercials, but this particular commercial, they just weren’t really into.

What Volkswagen did was go out and commission a copycat version of the Beach House song that sounded so much like Beach House that Beach House’s friends and fans started contacting them like, “Is this an unreleased Beach House song, or maybe is this the particular song that Volkswagen had wanted to use?”

Beach House basically found that they had no real recourse against this, because going to court to prove that they had ripped Beach House off would have been A, difficult to prove, and B, prohibitively expensive for a band that doesn’t have infinite resources behind it. We got to this point where it’s like, “Who even needs to license the indie song when you could just create a replica of it?” And I’m sure that there’s like AI versions of that happening now, too.

It was a really fascinating book about art and artists and also commerce. A lot of it feels like talent that was able to succeed in a new distribution environment and then rapidly getting sucked up into the maw of how large music institutions work — whether that’s the Apple Corporation, whether that’s places like Volkswagen or Urban Outfitters or Outback Steakhouse — and eventually getting subsumed, sometimes clumsily, into the mainstream.

Do you have insight as to what that could mean for our current moment? It does seem like the internet (social media, TikTok) is generating a lot of talent that is able to put their stuff out there at scale.

I think Indie Rock is still alive, but it doesn’t feel like it has the place and culture that it once had. I wouldn’t be so foolish as to say that it’ll never come back, but the way that technology and media and the framework of society are set up in a way where people who are operating in an underground or left-of-center environment find it incredibly hard to break through. It’s incredibly hard to even make a living.

We’re in a place where indie musicians more and more just do some side hustle or weekend warrior thing. I know there are probably some people who do like the idea of trying to make a career in the first place. I mean, certainly, elements of careerism led to some pretty questionable music in the past. I feel like we’re at a place where people are making the music, the people putting out the music, the people writing about the music or talking about the music on YouTube or TikTok — everybody who is in that game for the most part is doing it for the love of the game.

I think that is bound to create vibrant music and vibrant culture around the music. Whether that is something that has a chance to blow up, like indie rock did 20-ish years ago, I don’t know. Again, maybe that’s a good thing because I know there are definitely people who feel like the music was tainted and the culture around it was corrupted.

I don’t feel like I can plant both feet in that conclusion just because I like so much of the poppy indie rock. When we got to the point of Chvrches and Haim and a pop star working in the indie realm, I loved all that stuff. I don’t feel like I could come out as an out-and-out hater of that. But I could see someone making the case compellingly that maybe it’s for the best that this stuff has to stay underground.

But to me, it would be great if we found some way for indie rock or whatever the 2025 equivalent is — the burgeoning underground music that has a lot going for it. It would be nice if there were some way for that to explode out into the mainstream and make the mainstream a little bit more interesting. Right now, I feel like we’re in a really bland, blasé place when it comes to Billboard charts — when it comes to what you hear on pop radio. It’s just really white bread right now, and it could use a little jolt of something a little bit more creative, a little bit more weird. If it’s going to happen, it almost has to happen randomly, like through some viral TikTok thing. But the chance of building up something grassroots just feels so much harder. Does that make sense?

Yeah, no, it totally does.

As we finish up, where can folks find the book, and where can folks find you?

The book should be at all of your major retailers; you can get it at Bookshop, at Amazon, at Barnes & Noble; hopefully at your local bookstore. I have a landing page that directs people to the major retailers, and you can find that at my various socials. I’m Chris DeVille on Bluesky, on Twitter/X. I’m @chrisdevilleofficial on Instagram. I'm like the one millennial who never really used Instagram until recently because I decided I needed to use it to promote the book. But I’m fairly active on there now.

I’ve got Substack as well, which is suchgreatheights.substack.com, where I'm posting bonus content from the book.

I’m posting the chapter soundtracks from the book as playlists. Maybe once a month, I post a new chapter. You can keep up with me at all those places. And I’m continuing to update with more information about events. Done a few events so far. Got a few more coming up. I’ve had interest in lots of different cities, so hopefully we’ll be able to book a few more.

And then of course my writing. It goes up every day at Stereogum, where I’m the managing editor. Would be remiss not to mention Stereogum, which definitely was the launchpad that led to this book in the first place.

Edited by Crystal Wang

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Thank you so much for becoming a paid subscriber!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Numlock News to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.