Numlock Sunday: Chris Ingraham, author of If You Lived Here You'd Be Home By Now

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition.

This week, I spoke to Chris Ingraham, a Washington Post reporter who covers data stories about the economy and the world. Chris wrote a great book called If You Lived Here You'd Be Home By Now: Why We Traded the Commuting Life for a Little House on the Prairie.

The book is wonderful and tells a personal story as well as an economic one about price anxieties and skyrocketing costs slamming young families. Also, I’ve included several tweets from Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar in here because I find this smaller saga within Chris’ broader story deeply hilarious.

The book is available on Amazon and wherever books are sold.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

The book came out last week, it tells your story of how you ended up moving from the DC suburbs to rural Minnesota. It's amazing, could you go into the circumstances with which you discovered your newfound home?

So it's August in DC, and you know how it is, in August there's nothing going on. And everyone's pitching crazy at you to your editors because you can get them to green light crazy shit that they wouldn't do the rest of the year, because, you know, there's no real news to report on.

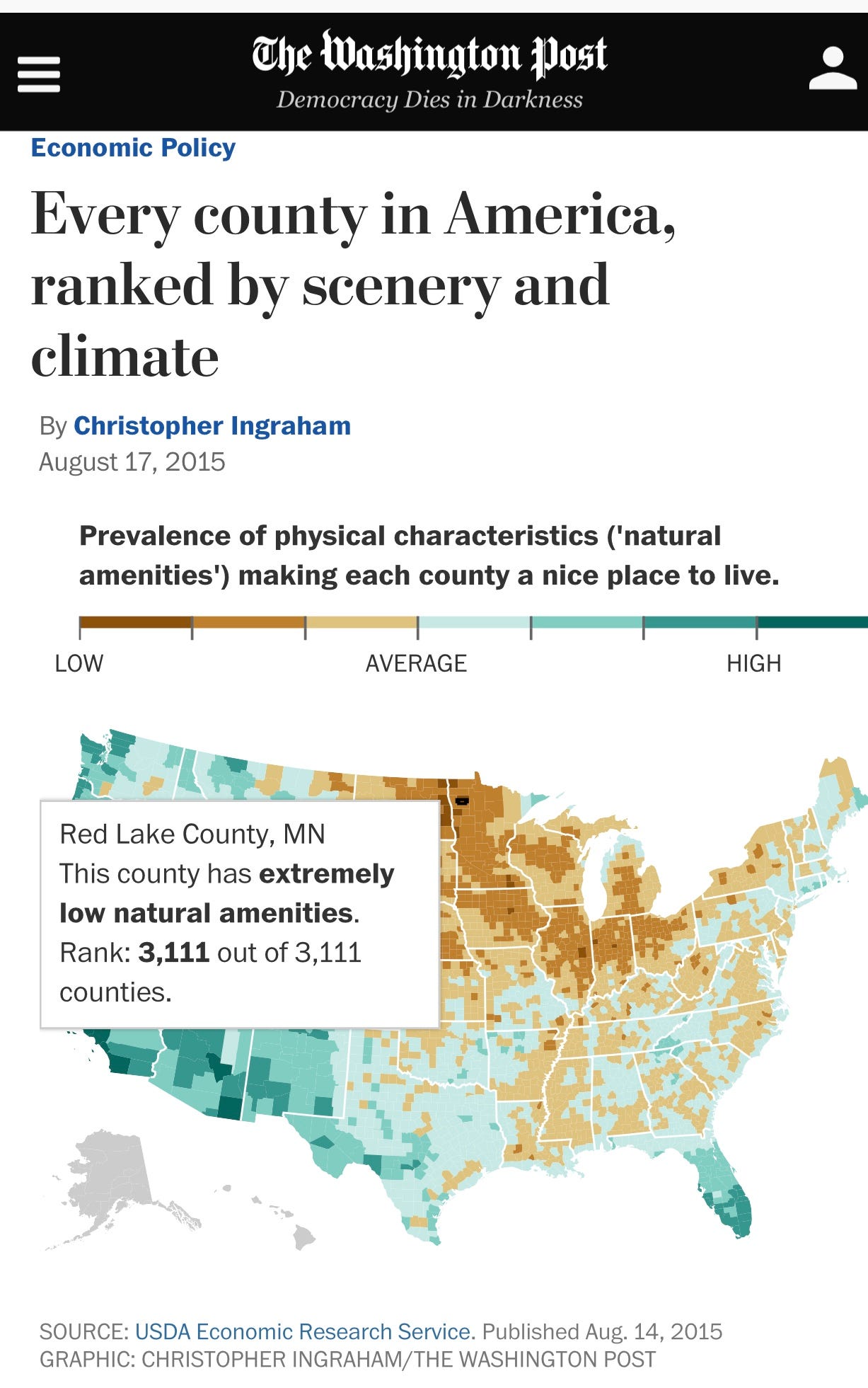

I stumbled on this report, this really cool data set, the USDA's Natural Amenities Index. It was put together in 1999, and what they did is they ranked every single county in the United States on more or less natural beauty. They looked at things like the weather and the climate, winter temperature, summer temperature, the landscape, things like typography and the presence of water like shorelines and lakes. They kind of mashed all these things together to figure out which places in America are the most naturally beautiful, which places have the most natural amenities.

In writing about that I called out — as you often do with the kind of ranking posts — the number one place, which I think Ventura County, California was the most naturally beautiful place to live according to USDA. But the place that came out dead last was this county in the middle of nowhere in Minnesota called Red Lake County.

And of course, I've never even been to Minnesota. I'd never heard of this place, so I want to call them out and I'm trying to Google them to get some kind of information that I can include in the story, but there's nothing. The only thing I found is their county website, and it's a classic small town, middle of nowhere county website where they have a calendar that's two years old and it just seemed like nothing was going on. The way they presented themselves to the world — when the fathers of Red Lake county sat down and decided what they were — they put together a section of fun facts. This is what you need to know about us. And the number one thing in the fun facts was that Red Lake county is the only county in the United States that is surrounded by just two adjacent counties.

Oh my god.

It's bizzare! And if that is all these guys got going for them, man, what it must be like to live there. So I include this throwaway line, about the absolute worst place to live in America is Red Lake County, Minnesota. And that was kind of the end of it. For about five minutes, until I publish the story. And then people from Minnesota, and particularly from northwest Minnesota, just started ragging me mercilessly on social media and via email. The Minnesota senators got in on it. Amy Klobuchar harassed me for a good half a day on Facebook posting photos of beautiful places in northwest Minnesota.

It was wild. So I ended up visiting the place actually a few days after that, on the invite of a local businessman. Then I'm like, okay, sure, I'm going to go visit this hick town, expecting it's going to be like Hillbilly Elegy or something, everything kind of run down and depressing. And I get there, and I actually ended up loving the place. I'm from a smallish town in the northeast, but this midwestern town — I hadn't spent any time in the Midwest before this — it was a great place. The people were very warm and friendly. One of the things that just struck me so much is that, you know, like any small town, they're very clearly dealing with their challenges. It was shrinking population, shrinking tax base, businesses leaving. But they weren't letting the challenges get the best of them. You could tell that they were rising up and they were meeting these challenges. They were still progressively trying to make their area a better place to be.

That really struck me because in places in upstate New York, where I'm from, you see a lot of places where that is not happening, or where you can tell that economic conditions have really gotten the better of communities. There's places that are really struggling and it wasn't like that here. After I got back, I did this follow up story. During the time, my wife and I — we had just had twins, so we had two year old twins — were starting to feel all the kind of crunches of city life. Our house was too small, we needed more space, I needed a shorter commute. I was commuting three hours a day every single day from Baltimore down to DC and I needed more time for the kids. But we couldn't see a way out. If we move closer to the city, you put houses out of reach. You can move farther away, but then I'm commuting even more. There is nothing to do. And so eventually my mom was who suggested, "Why don't you move out to that nice little place in Minnesota that you like so much?" And I was like, "that's really funny."

But you know, we kind of started thinking about it. And once one of those ideas takes place, it's hard to get rid of it. And so we started running numbers and I'm working out cost of living and broadband and schools, and then eventually we got ourselves to a place where we convinced ourselves it would've been fiscally irresponsible of us not to move to Red Lake county and four years later, here we are.

You're a reporter who uses data in so much of your work, and the book is kind of chock full of some cool stuff. There was this stat that the average American worker spends 9.3 days a year commuting. And in 2015, you personally spent 31.3, which is a figure that would certainly make me consider moving to Minnesota.

Literally an entire month, day and night, of the year I was spending commuting. One twelth of my life. One twelth of my time on earth was spent doing the activity that I absolutely hated the most out of anything. What a way to live. And the thing is, there are millions and millions of people who are doing that right now.

In the acknowledgements section of the book, the first person who you thank is not your agent, it is not your wife, it is not your editor. It is the USDA economist David McGranahan who in 1999 made that amenities index. Have you gotten in touch?

No, I haven't. I spoke briefly to some folks in the USDA shortly after the original story came out. It helped me realize that — this is for a normal person an obvious insight, for like people like you and me who work with data everyday and who have the tendency to put a lot of weight into data, this is something really helpful — but it just really drove home the limitations of data.

That kind of falls into two buckets, right? First, there's everything that this data is not supposed to tell you by definition. A collection of natural amenities data is not gonna tell you anything about the people who live there or what those people were like, or what the social situation is like.

But then just going beyond that, there's even the limitations of the data themselves. One of the funny things is, one of the reasons people in Red Lake Falls were so pissed off about that story is because Red Lake Falls is really a beautiful place. There are two rivers that meet right in town here, you have all these really picturesque bluffs and cliffs and things like that. Now the funny thing is, in the natural amenities index, counties got credit for having lakes or shorelines. But as I found out later, rivers were excluded from the calculation. So Red Lake Falls got no credit on the one thing that really makes it stand out within northwest Minnesota. There are both big ways and small ways that this is really instructive in the limitations of both what data is not meant to tell you and that of what it misses just as a result of human decisions.

Grand Canyon? Humongous hunk of crap. Seems like that's a pretty significant oversight.

You were very honest with yourself through the process, using some of the craft you do in your day to day. And I love this graphic that you had in the end where there was like a year by the numbers and you had a blood pressure decrease. Can you go into a little bit of how this experience reflected back on you, your health, your family and all that?

In DC, my house was a real challenge actually. I was on antidepressants and blood pressure medications, which I'm still on now, but it's a lesser thing, but I was dealing with those and that was from the stress of big city living. I was drinking a shit load to cope with these stresses. City life can makes us do all these kind of not so healthy behaviors. Since coming out here — I don't want to paint this as like a cure all for health or mental problems because moving to Minnesota is not going to fix a chemical imbalance in your brain — but in terms of very concrete things that I noticed, absolutely blood pressure dropping. Not being crammed onto a train with hundreds of other commuters for 15 hours a week really does wonders for your stress levels. At least for me, personally. I feel the sense of space out here and just having fewer people it's just so easy to get around and do things. If I'm in the middle of making dinner and I need to go to the store to get an ingredient that I forgot I can go and it will literally take five minutes cause it's so easy to get to town. Whereas, where we were in Maryland, a trip to the grocery store was an hour-long affair, at least, cause you hit traffic the whole way and everything.

So it's been great in terms of just helping me relax and feel more at peace. It's really nice because I'm still working at the Washington Post. I'm still kind of plugged into like the daily news and all the madness of it, but it is really nice to be able to shut down my laptop at the end of the day and just like go outside and see a big sky above me and all this green space in the yard and all the nature around me and just kind of step away from it. It was great.

I like how you really connected to your work, a housing crisis is going on in major cities and it seems like this is just such an interesting kind of guinea pig style "make a go of it" that is in so many ways telling a story about the broader economy by writing this, which is kind of cool.

The housing situation is just so crazy. We were looking at bigger places in Baltimore and single family homes around where we were for like $500,000, $750,000 and up. I'm like, what do people who live in Baltimore do that they're making this much money? Are they all investment bankers or are they just leveraging the hell out of themselves and taking money out or shortchanging their futures and their retirement to keep up to the standard of living here. You look at a lot of the problems in metro areas that we have like you have crumbling infrastructure that are not being reinvested in, you've got these commutes, you’ve got this insane cost of living and then you turn around and look at the problems that rural areas have — shrinking tax bases, shrinking populations, economic issues — you know, those are all reflections of the same thing. It's too great of a flow of people in one direction, flowing from small towns in rural areas to cities. If you were able to take a substantial portion of people in cities and relocate them to small towns in rural areas, it would both ease economic pressures happening in the cities and help bolster the fortunes of small towns. So how do you do that at scale? I have no idea. The one thing I can say from survey data is that if given their druthers, a lot of people would do this: 80 percent of people live in metro areas, but over half of them say that their ideal living arrangement is in a small town or a rural area. So there's a lot of pent up demand for this, but doing it in any meaningful way across the economy, well, I'm not sure how you'd do that.

You found this town by essentially writing it up in the Post, you've since moved there, you've bought a home, you’ve continued to grow your family. I understand now that you are in a romantic relationship with a local elected official. How do you respond to these allegations?

That's one of the funny things! Red Lake Falls needed a city council person. When we came out here, I kept my job and Brianna stopped working. She was working for the federal government and her job wasn't portable and she wanted to be with the kids for a while in their early years. That's just so crucial for so many different reasons, but she wanted to stay involved. So she's done a lot of volunteer stuff, she's on the board of an arts council and she's really active in the community up here. And there was a city council opening. And so she ended up running for the seat. She ran unopposed. And now she's on the city council! It's a crazy thing. I wrote this stupid line in this story four years ago and as a result of that we're here now and Brianna is making decisions that affect the future trajectory of that very place. It is wild to think about how that has worked out. Real Butterfly effect stuff there.

Where can people find the book? Any last advice for city slickers?

You can find the book anywhere. It's published by Harper Collins and at Amazon or your local book seller. Requesting it at your local library is always a big help. For city folks, I've heard from a lot of people who are in the same place as we were a few years ago, my advice to them is just sit down with your employer and then talk about if telework would be an option. You might be surprised that they might be more receptive to that than you might think, particularly if you're a valued employee and they like the work that you do. I don't want to be prescriptive. I don't want to say that everybody should do this, but I suspect that there are a lot of people who have wanted to do something like this and they may find that if they pursue it, they might find out that they actually can.

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Thank you so much for becoming a paid subscriber!

Send links to me on Twitter at @WaltHickey or email me with numbers, tips, or feedback at walt@numlock.news.

Thanks for another wonderful piece. I was working at a university in Silicon Valley and wanted to retire at 68. Three financial advisors told me that was fine, but I had to die by the time I was 80. They can be blunt. I had been saving up to 15% of my salary since I was 27, so this was a bummer especially since my wife is younger than I am. Silicon Valley was just way too expensive for retirement. So, we looked all around the U.S. for the best place we could afford to live. After much research, we moved to Eugene, OR. We sold our little house for a ludicrous price to a very nice 30s something techy couple and bought a gorgeous house in Eugene for cash. I continue to do my research here and am still a professor at my university. We love it. No traffic, no attitude, no pretension; great music, theatre, local breweries and wineries. The views are gorgeous and the weather mild. If you want to move to a saner life, and can do it, then, yes, it can be done.

Great story. Thank you.