Numlock Sunday: Chris Ingraham on dirty air and what it's doing to us

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition.

This week, I spoke to Chris Ingraham, who wrote a fascinating series of stories about air pollution including “Why dirty air hurts kids more” for The Why Axis. Here's what I wrote about it:

The EPA maintains a handbook that looks at all of the benchmarks when it comes to human exposure to chemicals. One somewhat counterintuitive reality is that the younger a person is, the more their exposure to air pollutants has consequences, mainly because on a per-cell basis they're simply breathing more. A 4-kilogram newborn, for instance, breathes 1 cubic meter of air per kilogram of weight, compared to 0.56 cubic meters per kilogram in a pre-schooler, and 0.22 cubic meters of air per kilogram of weight in a given adult. That's why when it comes to chemical exposure, youth exposure is of paramount concern.

I’m a huge fan of Chris’ newsletter, The Why Axis, and his decision to devote an entire month to the incredibly important but often overlooked issue of air quality is a great example of why. Today, we talked about what drew him to this issue, what he learned, and what doesn’t get covered enough.

Chris can be found at The Why Axis and on Twitter at @_cingraham.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

You wrote a really wonderful series of stories and investigations into air pollution. I feel like this story started as all good stories do as a vague salvo in the generational war at Gen X rather. Do you want to talk about what got you interested in this topic as a whole?

Well, it first came to my attention back when I was writing at the Post. One of the first stories I did at the Post was about one of the first studies that demonstrated that the air pollution outside can actually affect the productivity and intelligence of workers inside. They found that when air pollution was higher, workers were slower at this California fruit processing plant. And that's since been followed with all sorts of interesting stuff, how it makes our brain slower, how it reduces test scores. They found that air pollution, it has a measurable effect on politician speech, you can actually see the quality of politician speech decline as they're giving speeches outside in areas of higher air pollution. It has all these bearings on our lives. I've always been interested in — I wanted to focus on that topic specifically this month at The Why Axis.

One of the first things that I stumbled across while I was looking for things to write about was a retrospective study that just came out about lead. We talk about lead poisoning and it's one of the worst types of environmental toxins.

Over the years we found out that during the ‘60s and ‘70s in America, it was just everywhere. What this study did is they measured the blood lead levels of children using respective data from the federal government, going back to the 1970s to figure out okay, which generation of kids had the most lead exposure when they were young. And that was the meat of their findings.

There's a ton of the kind of research that it's not just vaguely alluding to an outcome. It's, "No, we actually kind of proved through various different statistical and scientific means that this is a very big contributor." The science is really sound on it. You just don't really hear folks talk about it. I feel like a little bit during the pandemic, people were talking a little bit more about ventilation, but it didn't really seem to go anywhere. Can you talk a little bit about how this issue plays out?

It's so tricky, right? Because the various estimates out there are that air pollution causes something anywhere from 50,000 to maybe 300,000 deaths in the United States each year. And the problem is these are all kind of quiet deaths, right? Nobody has air pollution listed on their death certificate, so it's hard to track. You can't track it in normal ways. What researchers find is that pollution, it contributes to so many bad health outcomes. They're learning about new ones, literally every single day new stuff is coming out. They know specifically that it's really bad for your heart and lungs and brain.

They find things like when there's a bad wildfire event, emergency room admissions for things like stroke and heart attack just skyrocket. So when you kind of quantify the effect of a given unit of air pollution on health, and you multiply that by how much pollution we have across an entire population, you get these absolutely staggering numbers. I think, yeah, as you mentioned, it gets overlooked a lot. I think it's because it's really hard to kind of pin a given death down to air pollution. But when you look at it in the aggregate, these numbers start to get absolutely staggering.

It is just wild to me because again, you had a post really just going through the latest research about air pollution and it's just so comprehensive. I'm always somewhat taken aback by how much energy people put into thinking about, tweaking, analyzing and really overhauling and monitoring their personal food diet. But there are other things that our bodies consume that you do not give any freaking thought to, you know?

Absolutely. One of the more interesting recent studies that came out — so we know a fair amount about air pollution outdoors. We have the thousands of EPA air monitors all across the country monitoring the quality of air outdoors. We know next to nothing about average air quality indoors.

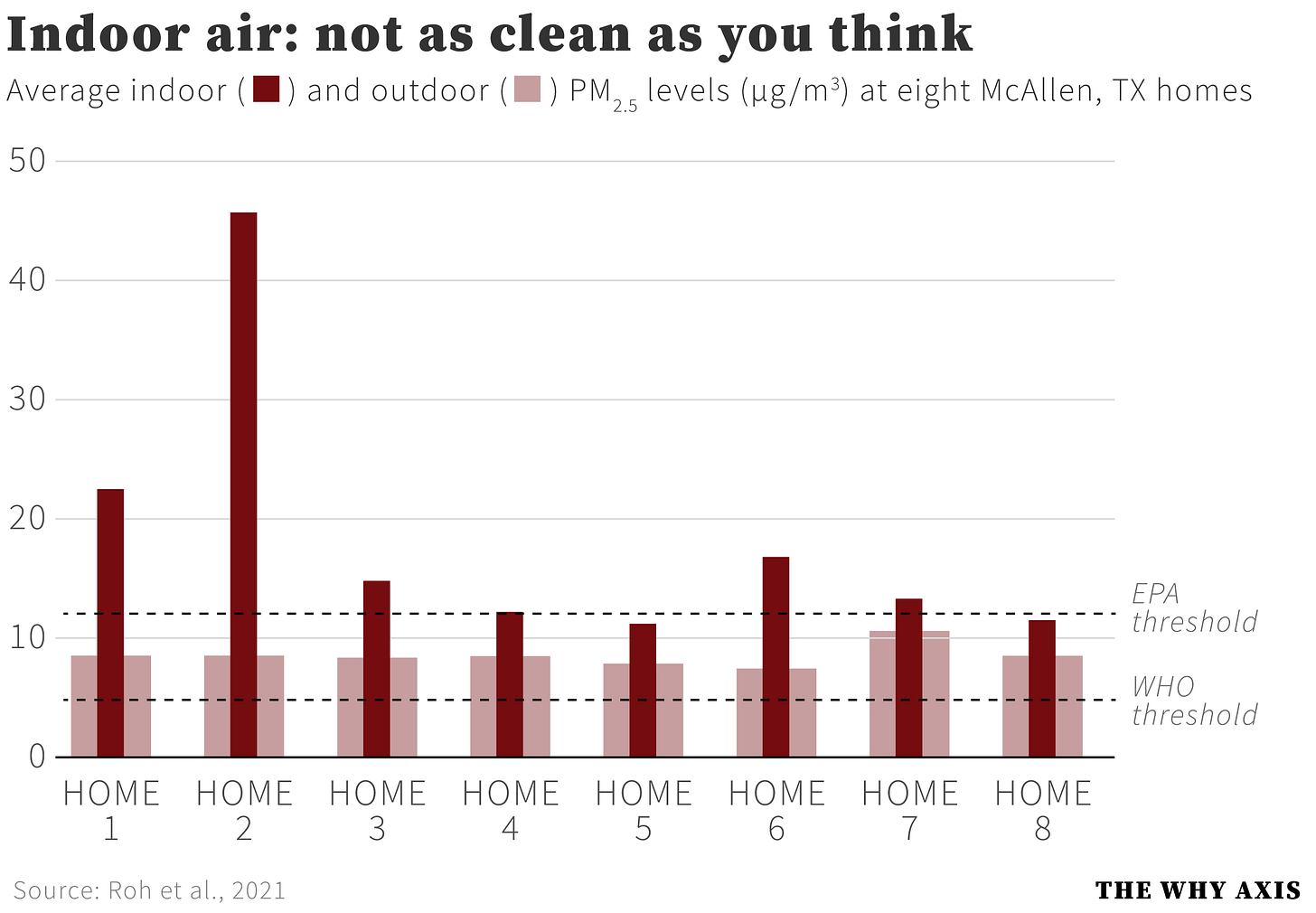

One study recently came out where they just basically tracked the air quality of eight homes in a Texas community over a period of several months to see how it related to the outdoor air quality at the time. And they found that in every single case, the indoor air quality, the stuff that we breathe inside in our houses, is worse than the outdoor air quality, and in some cases dramatically so.

Some of the houses indoors, they had air quality readings that were equivalent to Los Angeles on a really bad smog day. It's just madness that it's something that we know nothing about. And I think there is some growing realization of it. We're starting to see more kind of consumer-grade indoor air quality monitors coming out on the market. If those get more widely adopted, I think we'll see some more awareness of that. Another problem with it is that when it comes to dealing with air pollution, particularly indoor air pollution, there's this whole consumer market of air purifier products, but a lot of them are just based on absolute junk science. "We're going to blast some ions into your air that will eat coronavirus." A lot of it's just nonsense. The best things you can do, honestly, are open windows and just get a fan with a filter basically, or have a filter on your indoor heating system. The solutions are fairly simple, but a problem is that there are business interests looking to make a buck off of this. And some of them are doing it in unscrupulous ways.

I think that makes it harder for the average person. Because they're just, "Oh, I see these scammy ionization things on the TV all the time." And that's what they associate indoor air quality with. And so they think maybe it's something I don't really need to think about.

I think it’s also just so remarkable, as you pointed out, how clearly successful the interventions can be. You had one chart that blew my doors off, that was just leaded gas consumption and then the percentage of kids with high blood lead.

It's literally just one lags the other by five years. It's so remarkable how direct and effective some of the most simple interventions are, you know?

It's absolutely wild. The lead stuff in particular is just crazy. It's just crazy to think of what we were pumping into the air. Just to give you some sense of this, currently, the CDC guidelines, it's something like you shouldn't have more than, I think now it's 3.5 micrograms per deciliter of lead in your blood. If a kid has more than that, it's a problem and you need to take some steps to make that better. Back in the ‘60s and ‘70s, no kids had any, literally no kids had anywhere near that level. Instead, the typical kid had blood lead levels that were probably between seven and eight times that amount. I mean, that's just massive. Today, that would be thought of as a, just a huge public health crisis.

Back then, literally every single kid was walking around with that much lead in their blood because it was in the air. So when the EPA finally cracked down for good on it, and they brought the consumption down, they brought the levels and the air down and you can watch the lines go in parallel as you said, with a lag of a couple of years.

You always say correlation isn't causation. So of course, the researchers who actually study this stuff professionally, they've done a whole bunch of work doing various controls and analyses to ensure that, oh yeah, no, that's definitely a causal thing. That's not just a coincidence there. It's absolutely wild.

I think another interesting thing about air pollution is it's just a real unequivocal regulation success story. Those can be difficult to find because everyone likes to find the unintended consequences of regulation and, "Oh, we tried to do this, but then it didn't work. Or it created this other really bad thing that we didn't anticipate." With air pollution, it's pretty much unequivocal. The effects are just fantastic, huge return on investment, and really no knock-on effects that were negative from it.

I liked how the most recent segment in this series really focused on kids particularly, again, and the somewhat counterintuitive reason that air pollution impacts children more. Do you want to get into some of the research on that? That was really cool stuff.

One of the things that happened when you read about this stuff, one of the throwaway lines that happened, that appears at the top of pretty much every academic study of air pollution, is: "As we know, air pollution is much more harmful to kids than it is to adults." And you're, "Huh?" Like, why is that? Because you think kids, well, they're smaller than adults and they have lower lung capacities. So you think it'd be proportional, right? Pound for pound, kids are breathing in the same amount of air as adults, so you think the exposure would be kind of equivalent.

But that's actually not what happens at all. With kids, their lungs are larger relative to their bodies. And the thing is they breathe in, their pace of respiration is actually much, much faster than adults. They've studied the average amount of air people inhale in a day, right? It's something you never think about, how much air do you inhale a day? And they found that infants, they breathe in a total of about 4 cubic meters of air per day. And adults, they breathe in about 16 cubic meters of air per day.

So adults are breathing at about four times as much air as infants. The thing is, though, adults weigh a whole lot more than infants. They don't weigh just four times more than infants. So when you kind of, when you correct this for body weight, which is what really matters when you think about dosage of poisons or medicines, you're dosing by body weight, and that's the same thing with pollutants. When you're being exposed to a pollutant, what matters is your body weight and how much your body is able to handle that and process that pollutant. So when they correct for body weight, they find that infants are exposed to about five times as much air pollution per pound of weight as an adult is.

If you're walking outside with a little kid, his body has to process much more of whatever toxins, smoke, car exhausts, whatever it is that's coming in than your body does. So that's what makes it a lot more devastating to kids. It's that, plus a combination of kids' bodies are developing, and so disruptions to that kind of development can be a lot more harmful than to an adult where all your body systems are kind of already set in place.

You were telling me before we hopped on the call that there was some new research that dropped this week. I didn't really see it kind of covered in a lot of places; what went down?

The Environmental Protection Agency, they released their big annual air quality report, which contains the official data of how our air quality is. The weird thing is that, as you mentioned that, I noticed it's basically gotten no notice in the press. And these are really important numbers.

These are numbers that kind of determine whether thousands of people are dying or living or getting really ill or not. And it's just, as we talked about before, it's an unsexy topic, like, it's hard to attribute a certain given death to air pollution.

The latest EPA numbers came out. What they show in effect is that air pollution has increased again this past year. And particularly one of the more deadly ones, that one of the small particle pollution that gets deep into your lungs and heart and brain. It's on the upswing; it's up about 12 percent over the past couple years.

What we've seen is that since 1990 or 2000, there's been tremendous progress on cleaning up the air, but in the past five years or so, that progress has stalled and it's even looking like it might be reversing. With some of these types of pollution, I think the wildfire situation, that's a big driver because wildfires can be a huge source of this kind of pollution for some areas of the country.

That's part of it. But I also think that given everything that's come out recently, given everything that we're learning about how harmful even low levels of this stuff is, I think there's an argument to be made that it's time to think about tightening these guidelines, changing our understanding of what we think of as safe and acceptable, and I think that's what these numbers are going to suggest.

That's really cool. So again, all this is part of this, your newsletter, The Why Axis. You've been at it for a little while now. I guess, do you want to tell folks a little bit about it and where they can find it, some of your favorite work?

It's called The Why Axis, it's about data. Basically, my background's in data and design, so I like making charts and maps and finding, sending out interesting things about the world. Interesting things that might be getting overlooked by mainstream press. It's at the thewhyaxis.substack.com.

I'm just doing my thing there several times a week. Sometimes it's serious topics like air pollution, other times it's less serious topics: oh, I don't know, which color cats are the friendliest or how to maximize your toilet paper consumption. Did a whole big feature on toilet paper mass.

It's orange cats, right? Orange cats are the friendliest?

Orange cats, a hundred percent.

Unbelievable.

They're the best cats unequivocally.

Love it when data reflects the real world. Again, it is one of my favorite newsletters. It is really, really good stuff and so I would definitely encourage folks to check it out. Beyond that, where can folks find you?

Beyond that, I'm on Twitter @_cingraham. That's basically it. Twitter and The Why Axis. That's my kind of public-facing persona.

Thank you for having me, and I love Numlock. I love the variety of stuff that comes out of there every day. It's one of my favorite things to read.

Thanks, man. I appreciate that.

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Thank you so much for becoming a paid subscriber!

Send links to me on Twitter at @WaltHickey or email me with numbers, tips, or feedback at walt@numlock.news.

TED has a great talk about using plants to clean your air using plants NASA highlighted decades ago: How to grow fresh air, by Kamal Meattle. It talks about results from adopting such an approach on worker productivity.