Numlock Sunday: Dani Leviss on Ghost Gear

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition. Each week, I'll sit down with an author or a writer, behind one of the stories covered in a previous weekday edition for a casual conversation about what they wrote.

This week, I spoke to Dani Leviss who wrote “How to Exorcise the Ghosts of Crab Traps Past” for Hakai Magazine. Here's what I wrote about it:

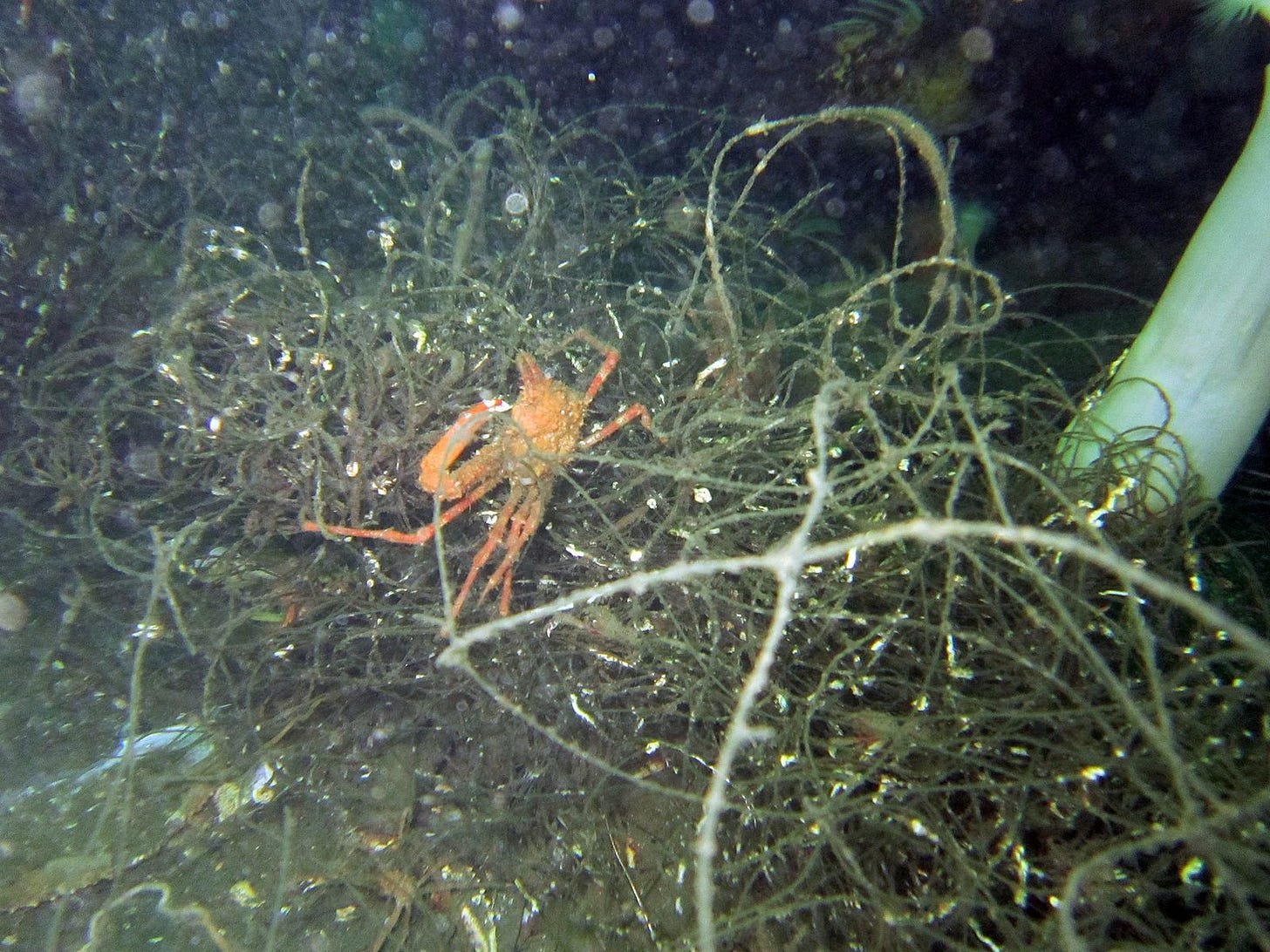

“Ghost gear” is the term used to describe fishing equipment that has been lost or destroyed over the course of use, and it’s a considerable problem. Globally, something like 640,000 tonnes of fishing equipment are added to the ocean annually. In 2017, it’s estimated that fishers lost 8.6 percent of traps, 5.7 percent of nets and 29 percent of all lines. This is a hazard not just for boaters and other fishers, but also for the ecosystems themselves, as just because someone’s not going to haul it in doesn’t mean that traps stop working. Re-baiting is when something is caught in the net or trap and — as they’re trapped — in turn becomes bait itself, perpetuating a cycle that can also kill non-target species like turtles or whales.

I loved this interview not only because the story is fascinating, but also because there’s a twist. Turns out one of the numbers in that stat has a fascinating backstory that has to be heard. It’s genuinely great.

Dani can be found on Twitter at @DaniLeviss and her personal site is here, and as always check out Hakai Magazine. They’re consistently great. I know a few editors read this, Dani is freelance.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Walt Hickey: How did you got interested in ghost gear?

Dani Leviss: Last year I was in an environmental reporting class for grad school. I just graduated in December in science journalism. I was in an environmental reporting class, and we had to do a feature and I wanted to find something where I could go to the place and see things in action. I was looking for things in New Jersey, this was early 2019, so I think I was searching on Google Scholar just for environmental studies in New Jersey and I found the Stockton study. I saw something about ghost gear, and I was like, "whoa, that's like a really cool term, what is this about?" I'm fascinated by anything with water — things happening to water, things that water does — so I was hooked immediately.

It's a global story, but you keep a pretty good focus on what's going on off the coast of Jersey. Abandoned fishing gear is a huge problem, what's driving that?

This started out as this very local story of what these people — the scientists and crabbers — are doing in New Jersey to fix this problem. They found that there are so many abandoned lost crab traps in the estuary near the marine field station for the university. I knew about fish and turtles and whales getting caught in fishing equipment, you see those photos all the time online. But I had no idea that it's not just nets, it's lines, it's traps, it's any gear that fishers and crabbers — no matter their size, whether they're a small boat or a big commercial boat — any type of gear can fall into this category. People toss their gear, or it gets lost, or there's a line that gets cut and now they can't find the buoy that was attached to their pot. But if they can't find their pot, then there's all these crabs and maybe other species that are stuck in the pot.

Environmental Protection Agency, Wikimedia Commons

You found a study that found that fishers lost 8.6 percent of traps, 5.27 percent of nets in 29 percent of all lines. They don't dissolve.

They just keep doing what they're designed to do: trap things and catch things. Whether somebody is bringing that haul in or not, the trap or the net is doing its job, it's going to still catch the fish. It's going to still catch the crabs and other things that happen to find their way into whatever type of gear it is.

You wrote there were 300 traps in the one kilometer area, this problem can get seriously out of hand.

There's one line in the story about this ghost trap rodeo in Florida that was really fascinating and I wish I had been able to get more of that into the story.

In Florida, something that they're doing is instead of having tournaments where people are going out to catch the biggest fish, this one group is having tournaments to clean up these same traps in Tampa Bay. The water there is so clear that they don't need sonar necessarily to be able to find things in muck, because the water is so much clearer than here in New Jersey. Somebody stands on a boat, they can swim and spot them and bring them up and the competition is like who can collect the most lost gear. That's amazing. But wherever fishing is happening, there's going to be lost gear. It's a problem here in New Jersey, it's a problem up and down the East coast, it's a problem on the West coast. It's a problem on every continent where there's coastal fishing

For a while it seemed that there was an adversarial relationship between folks who wanted to preserve ecosystems and then the fishing community. But as you illustrate, that's antiquated, that's not the case anymore, but some of the most avid conservationists are actually the fishing community, and they are actually doing some of the legwork.

The one thing that kept coming up is how much the fishers, the crabbers, the people who are using whatever ecosystem it is, they have the most knowledge about that place. No matter how much knowledge scientists have going in trying to evaluate what's going on, they're not there on the water every single day for 20 years or 40 years or whatever. It's the fishers and the crabbers for whom this is their livelihood.

Ray Boland, NOAA/NMFS/PIFD/ESOD.

They know the water, they know the ecosystem, they know the crabs, they know their gear. They have all this knowledge and if things are bad in the place where they depend on for their livelihood, then they're the ones that have the greatest stake in that ecosystem becoming healthy again. I think that kind of drive for them is what can fuel really good projects like this.

Well hey, thanks for your time, that should be good unless —

There was actually one number thing that I wanted to nerd out on.

Oh, most definitely.

I think you had highlighted it in your newsletter that 640,000 figure. Finding that stat could have been its own story.

It was so hard to find where that came from. A guy from Global Ghost Gear Initiative had told me about this number, and it was from 2009 and it's used a lot. I wanted to find where's the stat from?

I found the 2009 report, which was from a UN group, but it didn't say 640,000. I checked all the different sections that might have it, and I couldn't find it. So then, I found 6.4 million for total marine litter. So I'm like, okay, 6.4 million, 640,000, there's got to be a connection here. I thought I shouldn't be looking for the number 640,000 but a percentage: I finally found something that said 10 percent of the global litter to the world's ocean is this ghost gear.

I finally found this stat that people are talking about that's from 2009, but then where's the 6.4 million from? I found in that same UN report, they say that the 6.4 million is from, I think, like the ‘90s, something from the National Academy of Sciences.

I was searching elsewhere, and I found a 2015 study that also mentioned the 6.4 million global litter to the ocean. And they say it's from a 1975 National Academy of Sciences study. It was bad enough that the 640,000 stat that people are using constantly is 10 years old, from 2009, from the UN. But then it's really based on something from 1975, almost half a century old like that. That's weird.

You found a ghost stat!

That's a good way to put it!

This story had started out as an assignment for school, and in one of the revisions for the school's version of this assignment, I put in those two stats, I put in the years, and my professor was pushing to find something more recent. And of course, I wanted to find something more recent, but I put those stats in because I couldn't for the life of me find anything more recent.

Dr. Dwayne Meadows, NOAA/NMFS/OPR

When I talked with Kelsey Richardson from Australia, who's doing research trying to estimate more current stats on global ghost gear, she also mentioned that these stats are old and basically said that the 2009 stat was a back of the envelope estimation.

When I followed up with her a few months later, we were talking about the 1975 report and this was when she had just finally put out her study on those three percentages for the different types of gear. That 640,000 tons is based on information from 1975, which in turn was its own rough estimate. Her new information is probably the first real vigorous estimation.

That's so cool. You had a treasure hunt just to find that out. That's really awesome.

Yeah! I could have settled and just said, okay, 640,000 is from 2009 and gone with that. That's what lots of people do, whether they're a government agency or other journalism articles about ghost gear, that's what people have been using and saying. But I felt I needed to push because we didn't have a great grasp of how bad the problem is.

Where can people find your work? Where do you think it's going to take you next?

People can find my work on my portfolio website and then also my Twitter @DaniLevis. Like I said before, I just finished grad school. I've been also doing a lot of writing about science and math for kids. I've written for some Scholastic magazines and a daily news app for kids. And right now I'm working at filling in as an associate editor right now at Scholastic art magazine.

Now that I'm done with grad school, I'm trying to work up my freelance game. Even though I love writing about science and math for kids, I want to keep writing for grownups as well, and keep following up on water and maybe ghost gear.

I know a bunch of editors read Numlock, if you’d like to get in touch with Dani about work just reply and I’ll put you in touch.

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Thank you so much for becoming a paid subscriber!

Send links to me on Twitter at @WaltHickey or email me with numbers, tips, or feedback at walt@numlock.news.