Numlock Sunday: Dave Levinthal on the money, data and tech fueling politics

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition.

This week, I spoke to Dave Levinthal who wrote “The Wild West of political data sales can score candidates big money but raise privacy concerns. Here's how one politician is benefiting.” for Insider. Here's what I wrote about it:

From January to March, the 2022 congressional campaign of Christy Smith of California’s 25th District made $54,782.06 renting out the personal information of supporters to a digital consulting firm, an enormously common practice for federal candidates. What makes this interesting is that the campaign actually made more money leasing out supporters’ emails than it did from actual campaign contributions, where it pulled in $42,501. Lists of supporters have become really valuable assets for candidates, who even in defeat can make money by selling access to the people who kept them in the race to other PACs or candidates trying to shore up support or fundraising.

Levinthal’s beat covers all the myriad ways that big money mixes with national politics, from how campaigns make money, to lobbying, to the entire industry that exists adjacent to and intertwined with the party infrastructure that makes America’s elections so huge. This story gets at a fascinating sliver of that ecosystem, how a little bit of data can be worth a whole lot of money to the right buyer.

Dave and I actually go rather far back! My first job in journalism was an internship at the Center for Responsive Politics when I was a junior in college, where Dave was a money-in-politics reporter. Today we both work over at Insider and I’ve been looking for a chance to have him on for one of these.

Dave can be found on Twitter and at Insider.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

You cover the money and industry of politics. In just this past week you had a really interesting story come out about a House campaign for the next cycle that has found itself in a fairly innovative accounting situation when it comes to making money off of supporter data. What’s going on under the hood of some of these campaigns?

Well, when I was rifling through Federal Election Commission filings as one does — or at least as I do frequently — I came across something that I had never seen before. It doesn't mean that it hasn't happened before, but in this particular case, I found that there was this candidate in California. Democrat, her name's Christy Smith, she almost won back in November in California's 25th Congressional District, but lost by just a handful of votes. She's going to run again in 2022. She announced that last month. She's almost full steam ahead here at least with her campaign.

However, during the first three months of 2021, her reporting that she submitted and disclosed to the Federal Election Commission, as all candidates have to do on a periodic basis, indicated that she had raised more money from renting the personal data of her supporters than she had actually made from the supporters themselves.

It was a fairly de minimis amount of money. We're talking about $55,000 in terms of the money that she got from renting out her supporters data, a little less from donors themselves. It's still early in the campaign, but that was remarkable. I think it really underscored the overall point here, which is that if you make a contribution to a political campaign, if you even just give your email over to a political campaign, and certainly, if you are donating and then really involved, you become a commodity. Your information becomes a commodity, in a way that very few people actually realize.

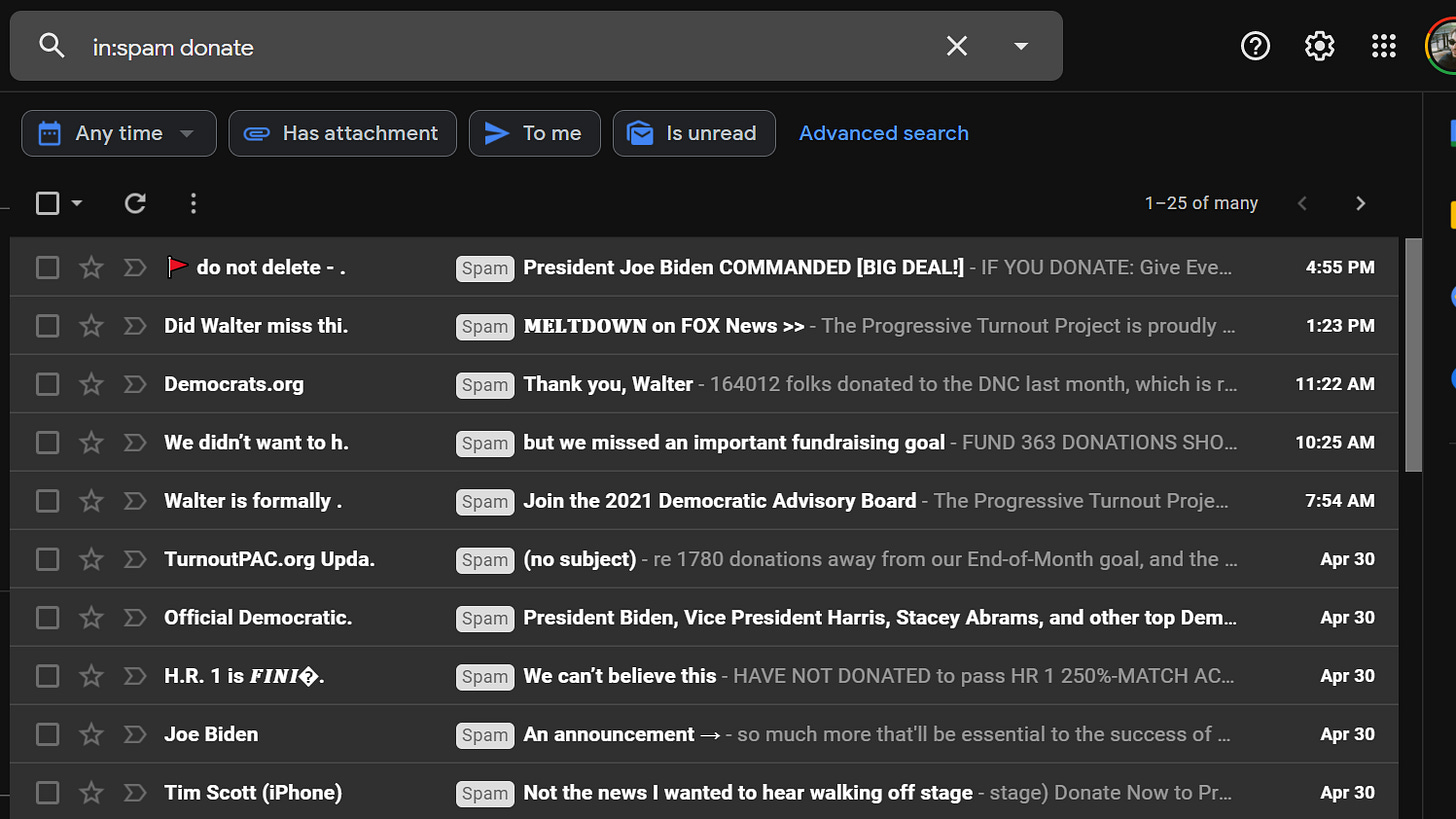

Yeah, the last time that I had any personal involvement in politics, the kind of involvement where I would be giving my email to somebody, was literally in 2008, and, no joke, I still get emails occasionally from people in that entire ecosystem of data.

I think people are very cognizant that if you put your data on Facebook, well then Facebook can use that to make money. But like, there's an entire infrastructure that you've reported about, within the American political sphere, that does just very much that.

And a lot of people might think, well, that's okay. They're probably sharing it with like-minded political committees. And in the case of Christy Smith, that was with a third-party democratic consulting firm that, yes, has lots of clients who are like-minded Democrats.

But nothing is stopping this third party or, for that matter, any third party from taking that data, once it gets it. And once it rents it, depending on the terms of that rental, and then doing something else with it, and turning around, and making a profit, or basically re-renting, or reselling, or repurposing your data many, many times over going forward.

If you've ever signed up, for example, for an email list, or if you've ever made a donation to a particular candidate, and then you suddenly start getting lots and lots of emails, and messages, and solicitations from other candidates, but you don't remember signing up for their list, there's a reason for that. It's very possible that you are information has become commoditized, and as a result, you're being marketed by political entities in the same way that you would be if you had a corporate transaction, or a retail transaction, and handed over your personal information.

So, bottom line, buyer beware, and also donor beware, too.

I think I can surmise the answer to this question based on your reporting so far, but is the FEC looking into any standards or practices about this, or is this just kind of the wild west?

It's the wild west. It's about as laissez-faire as it could be, there are very few rules and regulations, governing this type of activity. And, hey, Democrats do it, we're picking on a Democrat here, but Republicans absolutely do it too. Donald Trump was making available his supporters information in a major way, as many presidential candidates have definitely done these past years. Obama did it to some degree, Mitt Romney did it.

In a lot of cases, there are professional data brokerage houses that trade in this information. They buy it, they sell it, the re-sell it, they repackage it. If, for example, you Walt, or me, or anyone else listening, wants to go and, for example, get the most esoteric information out there — if you want to find a Catholic women, of an age between 20 and 29, who really loves buying stuff on Etsy, and their favorite color is blue — you might be able to find a list! I'm only partially exaggerating here.

I mean, the level of detail, and also the level of data combination that you see out there with some of these brokerage houses is wildly sophisticated, and also a little scary too, that these places know that much about you, and can get that information into the hands of somebody who's willing to pay for it. Some of this information is definitely coming from non-political sources, but much of this information is coming from political sources, and being packaged together with various data sets that may enhance and build upon the information that they're getting from their political clients.

Your reporting has just been so illustrative of just how much of the business of politics is business. There are groups that will do fundraising for folks, but take 80 percent of the gross. There's lots of different ways that people can get a bite of the pie.

Absolutely. Political consultants, for example, there's a reason there are so many of them out there, because it is such a lucrative business. Political campaigns oftentimes will spend a significant portion of their budget basically cutting donations to folks who do work for them, and who are not part and parcel of the campaign, but are being hired by the campaign to do work. This is a necessary part of major campaigns, whether it be a House campaign, a Senate campaign, Gubernatorial campaign, all the way up to a big Presidential campaign.

I think, out there, voters may have a kind of gauzy, idealistic version of how a campaign is run. That it is being driven by volunteers, and people showing up at the campaign headquarters, and making phone calls, and putting together lawn signs.

That happens, absolutely. And that's very important, but at the same time too, there is some real big data action going on here in 2021, that just would have been impossible 20 years ago. It's out of its embryonic stage, and was still very much in its developmental stage, right around the time Barack Obama was running for office, kind of upping the game and upping the bar for everyone running for national office, or for a major office in the country, from a data standpoint.

Yeah. I think that there's a very West Wing view of how politics works, but it's also The Social Network, and it's also The Producers.

Absolutely.

On that second note, you just dive into these reports and are able to discern some of the large flows in American political money, but like you wrote about how $2.7 million was just up and stolen from political committees.

This is true, we did an investigation a few weeks ago that looked at the 2020 election cycle, and went through all these reports to try to figure out a minimum number of how much money got stolen from federal political committees. It ended up being about a minimum of $2.7 million. In the scheme of things, when we are measuring the price tag of federal election in the billions of dollars, that's still a very, very small amount, percentage wise.

But think about that for a second. $2.7 million just straight up stolen, jacked from the digital sphere, from cyber thieves, or people who are ripping you off, by duping your credit card, all the way down to just very traditional trappings of theft, like check washing, and people going into the petty cash drawer, and whatnot. But it really just underscores the point that many of these committees, I don't want to call them fly by night operations, because that's not true in all cases, but they may not necessarily have the best security procedures put in place.

And we're talking about some pretty well-known political committees here. The Biden Presidential Committee — he had about $70,000 stolen from it during the course of the elections. The Wisconsin Republican Party, and it was big as well, more than $2 million. The Teamsters, the union, got money stolen from it.

And even Google, Google has a political action committee. They donate some money to various politicians, Republicans and Democrats, and Google loves to brag about how great their security is. Well, the security wasn't good enough in their political action committee, to keep it from having about $2,500 stolen from them, and Wells Fargo, its bank wasn't able to recover the stolen funds. So, a little bit amount of money, but still, you would expect that Google might have better security features in its own system. And in this case, somebody was able to go ahead, and take that money out of Google's account.

I mean, you had a great line in that story, that the old quote about robbing banks, it's like, "well, that's where the money is." And now, there's an enormous amount of money in politics. Again, I've known you for 10 years, you were my first boss. You have been in this game for quite a long time, what are the changes you’ve seen in the space?

Political money is truly like water. It will always find a path. And we're talking a lot these days about, for example, Corporate Political Action Committees. And everyone seems to be running away from that. Democrats don't want to take PAC money because they see it as sort of an icky, gross, tied to the corporate world. And now Republicans are running away from Political Action Committees, because they are really angry and pissed off that corporations such as a Major League Baseball or Coca Cola, are supporting legislation that they disagree with, or not supporting legislation that they want to put forward.

And Ted Cruz says, hey, I'm not going to take PAC money anymore. Well, hey, that's his right. And that's, everyone's right, to take PAC money and not take PAC money. But we're focused all on PAC money right now, when very few people are talking about, for example, again, that Joe Biden's Inauguration Committee, the committee that put on all the festivities around Joe Biden's inauguration, took, we reported, well into the eight figures worth of direct corporate contributions, to fund those fireworks that were going over the National Mall, and creating a nationwide broadcast, and whatnot.

And that got very little attention. So, oftentimes, the corporate influence efforts are so multi-pronged, and so sophisticated in their own, that much of it goes below the radar. And Donald Trump, I think was very much an expert at this, during his four years in office, getting money from all sorts of different sources, and also monetizing individual support, in a very profound way.

It seems the connection between the technology and the fundraising component of it have really gotten very locked in sync. Now that the fundraising and the small donors are such a big part of it, it really does seem to have gone national in a way that you hadn't really seen that even in like 2008.

You struck on it right there. As I mentioned a little while ago, 20 years ago, if we were having this conversation, we would not be talking about the nationalization of most U.S. Senate campaigns, certainly not the nationalization of U.S. House campaigns.

Twenty years ago who in New York City was going to care about some recent Arizona House race? Not too many people. And if they did, we collectively did not have a means of digital communication to make it such a big deal from a financial standpoint.

Twenty years ago, we were still writing paper checks to make political donations by and large. Now it's, effectively from a political standpoint, just like Amazon. It's a one-click political donations. And if you want to go, and habitually make donations to candidates that you'd like and support, because you just simply want Democrats to kick the heck out of Republicans, or Republicans to kick the heck out of Democrats, well, yeah, you can do that very easily.

We see, time and time again over the past several years, instances where a single individual may have made hundreds, or even thousands, of individual political contributions to various candidates that they philosophically are all excited about. And it becomes like a drug, and it's sort of like the pandemic-era shopping relief, it's like pandemic era political support relief, to try to own the libs, or try to beat up on the Republicans. So, it's just kind of the way that it works right now, in a way that would have been entirely unpredictable not too long ago.

That's really interesting. These parasocial relationships that people have had historically with media figures and celebrities are now getting nationalized on politics too, which I'm sure it's going to have great outcomes for this country.

Of course.

Dave, where could folks find you, and find your work?

Well, you can find me on Twitter, @DaveLevinthal. And that certainly, Businessinsider.com and insider.com, where you and I, both live.

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Thank you so much for becoming a paid subscriber!

Send links to me on Twitter at @WaltHickey or email me with numbers, tips, or feedback at walt@numlock.news.