Numlock Sunday: Jeff Yang on The Golden Screen

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition.

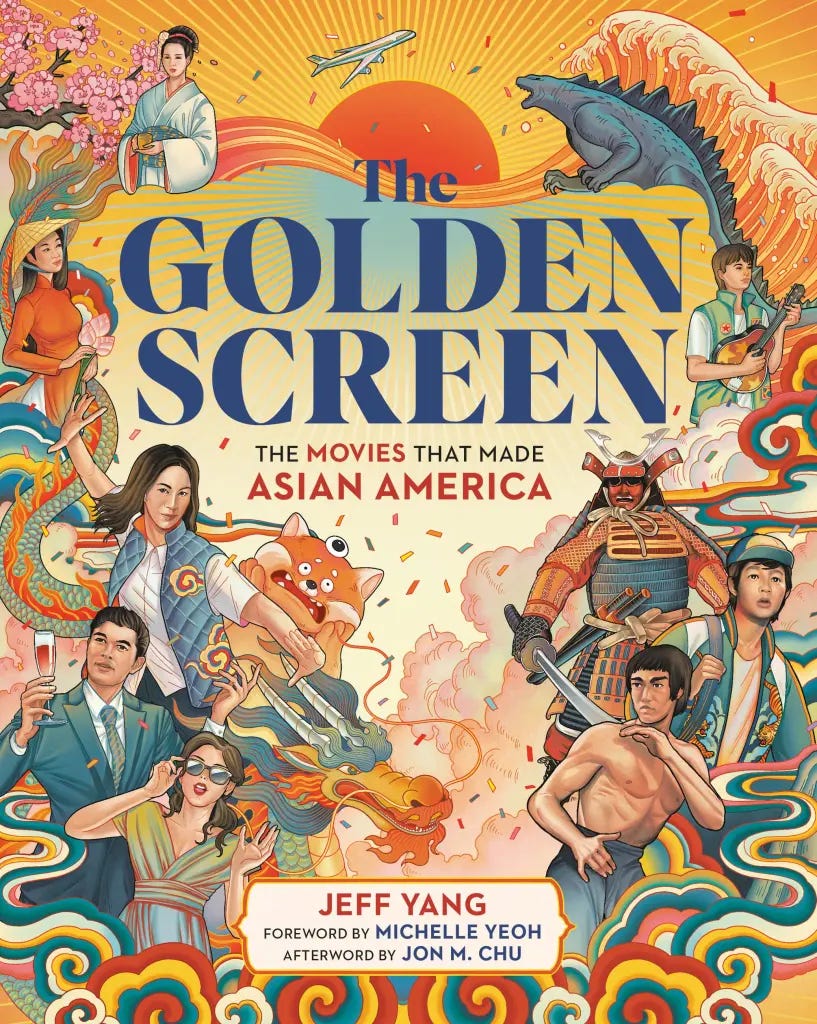

This week, I spoke to Jeff Yang, who wrote the new book The Golden Screen: The Movies That Made Asian America.

I met Jeff because we both have pop culture-related books out this Fall and our paths crossed often enough where I just had to check out his book. I grabbed a copy and absolutely loved it, and I wanted to have him on to talk all about it. The book is a deep dive into the history of Asian-American cinema, and is as a result also a very cool history of cinema as a whole. It’s a great read and would make a great gift, at that.

We spoke about the intersection of the Asian population in the United States and the movies, the earliest history of Asian representation in film, the reasons why there has been such an exciting surge in filmmaking by and about Asian-Americans in the past twenty years, and also easily one of the most interesting anecdotes I have ever heard about the Fast and Furious movies.

The book can be found wherever books are sold.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Jeff, thank you so much for coming on.

Thank you so much for having me, Walter.

You are the author of The Golden Screen: The Movies That Made Asian America. It came out in October. It's really good. You run through a history of influential films that were both made stateside and made internationally, but nevertheless had a fairly indelible mark on cinema and also Asian filmgoers. Just to give you the basic question, what got you interested in this kind of approach?

Well, it's fascinating because it's something that I think both of us actually argue as a thesis, this idea that you are what you watch, to cite a certain book which I'm a big fan of.

That's in both directions, right? On the one hand, it means, well, sometimes we want to watch the things that we are. That's certainly one of the arguments for representation, that people need to see themselves on screen, that there are psychological benefits, that there are sociological benefits to seeing diversity that maps out to the diversity of the actual population in the content that surrounds us.

There's this other frame as well, and I think it's the one which we're both fascinated in, which is how do the images that we consume change the way we see ourselves and the world around us? I mean, my argument is that, if you look at the history of Asian Americans in particular, ours is a community that has been framed by the ways that we've been represented in media from the very beginning of our arrival in the United States. Again, stop me if I am going into too much of this soapbox here.

Please, go on.

If you look at the earliest mass or earliest volume immigration of Asians to America, which would be the Chinese in the mid-to-later 1800s, what you'd start to see is that the reason why Asian peoples, Chinese people in particular, were first lured to America was as cheap labor, and it was cheap labor in particular to essentially serve as a counterweight to freed slaves and their demands for living wages and the like. We were essentially the first scabs. Chinese immigrants were positioned in such a way to be a wedge population for labor purposes against the African American population as they started getting paid for their labor.

Now, the problem with that, of course, is that we also undercut the wages of white workers, and that invariably led to outrage and, ultimately, backlash from the labor movement. What we started to see were cartoons, op-eds, posters, and full-on media campaigns designed to otherize the Chinese labor force that had been brought to America, in ways that were designed to platform the idea of excluding the Chinese. And these were images that framed the Chinese as being pathological, as bearing disease, as being hordes of vermin breeding too rapidly, eating disgusting things, and potentially serving as a threat to both social peace and to white women.

I mean, the whole range of different stereotypes that came out of this era can actually still be seen, because those are the stereotypes that ended up working their way into popular culture. Things that start on posters and in propaganda campaigns invariably end up being part of the larger image-making machine that is Hollywood and that is pulp fiction, and that is all the other ways in which the masses of America consume identity.

I guess the argument here is that, from that era, these archival stereotypes have framed the way that Asians have been represented ever since and, because they're always designed to be about othering and exclusion, basically served as a rationale for kicking out the Chinese and then the other Asians from America. They were toxic stereotypes and, again, renewable ones, because every single time that America had a war with Asians, for instance, those stereotypes would be revived. Every time that there was an economic tension between America and Japan, America and China, we'd see the same kinds of imagery resurfacing; reduce, reuse, recycle, again and again, just set and repeat.

That is one argument for the idea that images make us. Our social condition, the policies that framed our population's ability to live in America, even, were absolutely defined by the images that were put in front of us.

I want to also go back a little bit in time because one thing that I came to appreciate when I was reporting on some topics of diversity and inclusion is that, if you go back to early Hollywood, certainly, there were people who were playing racial animus against one another, but you had Asian movie stars. You write about Anna May Wong, I believe, as well as a number of other serial detective features that feature prominent, swashbuckling Asian American actors. It wasn't that we never did it before, so much that it was deliberately erased. Do you want to speak to that a little bit?

Yeah. Anna May Wong and, actually, Sessue Hayakawa are probably two examples of very, very early Asian film stars who could have been enormous, who could have been leading ladies and leading men. The reasons why their careers got derailed is undoubtedly because of the racial climate of the time.

Sessue Hayakawa was seen as such a suave and seductive and attractive individual that women were actually warned when they were going to see movies that featured Sessue Hayakawa that they might faint in the aisles. He could have been Errol Flynn, but the problem, of course, is that Errol Flynn had to kiss women. Any leading man had to. That sort of romantic component required two people on screen who were of the same race, because the Hays Code at the time made it essentially verboten for interracial relationships to be depicted on screen.

Because there were, at the time, no Asian women who were of the same tenor of potential stardom, I suppose, as Sessue Hayakawa — Anna May Wong came a little bit later — and more importantly because people just simply didn't want to accept that there could be two Asian people on screen at the same time, Sessue Hayakawa could never actually be a lover on screen. He always had to be a manipulator, a seducer, a fiend, a rapist. In his most famous film, The Cheat, he plays this incredibly wealthy businessman who tends to seduce and then abduct the white female lead by essentially extorting her with money. Even so, people actually went to that movie to see Sessue Hayakawa. He was the most magnetic thing on screen. They just could never see him as somebody who belonged with a female romantic lead. He always had to be that predatory force on the outside.

The same could go for Anna May Wong, right? Anna May Wong, from the very first time she appeared on screen in a film called Toll the Sea, she was magnetic.

People thought she was a brilliant actress, but there was no role for an Asian American leading lady on screen because she was not allowed to actually have a physical romantic relationship where she would end up with a white lead, and they would not pair her with an Asian lead. It took years before she was able to make films that put two Asians on screen at the same time. One of the first of those was a film called Daughter of the Dragon which actually featured Sessue Hayakawa in one of his early talking roles as her male counterpart. He was an FBI agent seeking to essentially foil the plot of the dastardly devil doctor, Fu Manchu, and Anna May Wong played Fu Manchu's daughter who ends up in this unfortunate, star-crossed mutual attraction with Sessue Hayakawa's FBI Asian character because, of course, it's loyalty to one’s father or loyalty to one's heart. That's the inevitable consequence of such triangles.

The problem, again, being that because of the racial tenor of the time, even with two Asian people positioned as walking off into the sunset together, the outcome of the movie was instead that they killed each other and barely even touched hands before collapsing to the floor after thwarting the diabolical Fu Manchu's plans. Stuff like that was de facto or the reason why a lot of the earliest stars never really made it, because they weren't given the range of motion to play roles that were necessary to step into that role of being the leading man, the above-the-title individual.

Again, last thing about Anna May Wong: Even when there was a purpose-built project that Anna May Wong could have stepped into and played the lead of, like The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck, a book written by a white woman being directed by a white filmmaker which, unfortunately, ended up starring an effectively mostly white cast despite the fact that it's set in China with all Chinese characters? Anna May Wong actually attempted to use whatever she had to get the leading role that, instead, actually went to a woman of German-American extraction who ended up winning the Academy Award for her performance. This was the kind of uphill battle that Asian Americans in that earliest period had to wage simply to be represented on screen.

Yeah. It's a pervasive theme throughout the book, again, just the challenge of getting this stuff made, but one thing that I really enjoyed about your book is that it's also, besides being a history of Asian American cinema, it's also just a history of cinema as an art form. There are so many movies that you cover in this without which the entire film industry would be completely unrecognizable. You wrote about things like Seven Samurai; like Akira, which is one of the most visually influential films ever made; Spirited Away, obviously; even things like Rush Hour. There are just so many films in this without which what we would consider mainstream cinema just simply wouldn't exist.

Absolutely. The history of Asian American cinema is the history of cinema, right? This is true for every multicultural group represented in this country. We have deeper roots within the ways that America has been constructed in the imagination and on the ground than most people actually recognize or accept.

One of the early decisions with the book was that we wanted to be inclusive not just of films that are Asian American because of Asian American filmmakers in Hollywood but also actors and films from Asia that made a big bang here in America. Because, ultimately, the book was really about the experience of watching cinema and watching Asian images on screen and how they change us, and that required us to transect all three of those different dimensions.

I will say that the other decision I made was not to make the film listings chronological from earliest film to last, but rather to organize them into specific themes. That was in part because, given the number of films involved and the multiple industries included, it was just noisy to put things end-to-end and look at this as a chronological history of cinema itself. What was more interesting to me was to look at the ways that certain kinds of images evolved over time, like images of men and women, like images of family, like images of immigrants.

If you use that lens, the lens of a type of story being told, what you'll see is from the very beginning, from the earliest times, those stories were being told to the present. There's a very real set of changes that occur that are in lockstep in many ways with the ways that America at large was willing to accept and embrace Asians in those capacities in the real world.

I didn't have a chance to make a tally of it, but I had to say it seems like a significant percentage of the films that you cover in your book are from, let's just say, post-2000. There really has been, particularly lately, a recognition that this is not only a vibrant genre and realm of storytelling, but also that this has become a very significant market opportunity. Obviously, the decision to group these by thematic ideas was really compelling, but also, within these different themes, have you seen different films make a mark?

Yes. Well, first, the 2000s benchmark for the real boom, if you will, in Asian representations on screen, that's not entirely accidental.

I mentioned that for centuries in America, Asians were specifically excluded from immigrating to the United States first with the Chinese Exclusion Act, and then all Asians were essentially barred from coming to America because the Asian continent was labeled the Asiatic Barred Zone. There was a legal restriction against mass immigration from Asia. Trickles of people came in with special visas for scholarship purposes, going to college, et cetera. Of course, after the Great Fire in San Francisco, there was a stream of Chinese who came to America through what was known as the “paper son” loophole. All the records of who was actually born and belonged in America had been destroyed in the fire and, as a result, enterprising Chinese managed to get other people into the country by simply saying, "Oh, this is a long-lost son that you don't recognize. Yes, his records were burned in the fire."

Effectively, for all intents and purposes, until 1965, the number of Asians coming to America was very, very small. If you actually look at the Asian population, it goes from something like 1 percent or much less than 1 percent to, within the space of just three decades, 4 or 5 percent of the population. That's because, in 1965, the Hart-Celler Act basically eliminated the racialized quotas that prevented immigration from Asia writ large and, in fact, encouraged it, because there was a real demand for skilled labor, for individuals with degrees: doctors, engineers, nurses, et cetera. Those individuals were essentially invited on a frictionless visa application process to come to America, so, post-1965, you had this big bulge in Asian immigration in the United States.

Three decades after that, the kids who were born in America and growing up, generally speaking, with advanced degrees or with the benevolent status of living off their parents' sweat and tears to acquire white-collar status, ended up moving into the workforce, and more and more of them were embracing work in creative professions. The very first wave of people born in America, generally speaking, were aimed at more stable professions than creative industries. By the time you actually got to the late-1990s and 2000s, you started seeing people rebelling and becoming things like journalists and novelists and, yes, filmmakers and actors in much larger quantities. That's why you started to see, almost by definition, a bit of a bulge in the number of films starring Asians and made by Asians in the United States around that era.

Yeah. It's exciting that you pointed that out because, when I read this, I hopped around to some of the film franchises and films that I love the most, and you have an entry — it is on the sillier side when it comes to the caliber of films in this — but you have the The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift, and you write about how not only was that an important reset for what now is one of the most consequential franchises for Universal, but it was one where it even seems like they misunderstood some of the appeal of their characters to the point that they killed off Han and then, eventually, had to bring him back due to how popular and compelling he was.

Absolutely. Sung Kang's character was a fan favorite. Fortunately, in the Fast & Furious franchise, no one is dead for very long anyway, but, yes, it actually goes even deeper than that.

A little-known story here, but the Fast & Furious franchise actually began with the optioning of a story that had appeared in Vice Magazine. That story was written by Ken Li, who's now I think an editorial director over at Reuters. At the time, he was my intern at A. Magazine.

Oh my God.

Which was one of the early Asian-American publications. He came to me saying, “Hey, I have a story I want to write. I don't know where to write it for. Should I write for the magazine?” I was like, “No. This thing you should pitch to a bigger opportunity because this is a great story. I'll connect you with my editor at VIBE Magazine.” I'd been writing for VIBE, and my editor there, when he heard the story, said, “We're going to give this cover space.” It was a story called Racer X, and it was about basically Asian American illegal street racers who were taking over highways in Brooklyn and running their own illicit, mostly import car races. This ended up getting licensed by Universal to essentially be the IP around which they constructed the very first Fast & Furious.

Of course, the first thing they did was eliminate almost all the Asian characters. I think Rick Yune was the only Asian actor who is a character there and, of course, he's a villain, but they whitewashed all the characters, they built a franchise around it, and it's not until they actually bring in Justin Lin and do Tokyo Drift that the Asian and Asian immigrant roots of this illicit street racing underground was finally acknowledged. Nobody talks about this history, but The Fast and the Furious is actually our story. I mean, importing and car culture and underground street racing car culture here on the West Coast and also in New York was Asian American first, and it was taken away and turned into The Fast and the Furious by people who realized that, if they simply just lighten the complexions of the characters involved, they might be able to actually make a mint off of this.

My jaw is on the floor right now. That is an incredible story. I've never heard that before. Your role in that is so cool. Wow.

I mean, these are some of the hidden stories around a lot of these things. When you are constrained, let's just say, when markets are distorted, weird things happen, right? The purposeful restriction of Asian stories essentially repopulated with white actors, the restraint of Asian talents both in the restriction on immigration and then, later, on simply hiring in Hollywood, it meant that the natural evolution of stories and images on screen were pushed in different directions.

The reasons why people associate Asian faces with villainy is in part because the only roles that were available for actual Asians were the bad guy roles, these bit-part, die-screaming type roles either in war movies or in Yellow Peril conspiracy films or like Oddjob, henchman-type roles for big budget spy thrillers and the like. There are people like James Hong who have done hundreds of these roles. I think Hong has around 700 film credits to his name, and I think he estimated at one point that well over two-thirds of them were people who would probably be in jail. That has real effects for how people start imagining Asian people in the real world. You trust them less. You see them as potential threats. You don't want to actually live next to them, and you wonder what they're doing in their little houses when they cluster together in ethnic enclaves. Masses of Asian people become a threat, a peril, and we've seen the real-world consequences of that throughout history.

You have been so generous with your time, so I just have one last question for you. Sprinkled throughout the book, for each film, you actually speak to someone for whom that film really meant something. It was really cool to see these because, again, I saw so many of these film titles and I knew that so many of them meant so much to my Asian friends, films like Bao and films like Crazy Rich Asians. Really, they meant a lot to people who I care about.

It was really cool going through your book and seeing you talk to either journalists, critics, or creators about things that meant a great deal to them. I guess, is there anyone that really stuck with you?

Wow. I mean, I would say that there is one quote. I think it was Ana Johns talking about The Namesake, where she discusses having to leave the theater not because she disliked the film, but because she was in tears from having seen this story unfurl on screen that in so many ways mapped out the aspects of her own personal life as an Indian-American, and as somebody who's lost her father, I believe. She was talking about the scene in which Kal Penn, the protagonist of the film, is wearing his father's shoes as a means to remember him. She recalls having done the same, that when her father was not there, she would fit her tiny feet into his much larger shoes and just remember the gap that that represented in her own life.

I mean, that struck me hard. It reminded me of the fact that, for each and every one of us, the cinema is ultimately a personal experience. We sit in the dark. We're facing a magic mirror. We try to look at something, anything on that screen that resembles us, that connects to us and, when we find it, we're immersed in it, and then, every so often, when there is a big humor beat, when the hero gets the girl, when the villain gets his due, everybody laughs, everybody boos and ahs, everybody screams, and that brings us together as an audience. It makes us aware of the fact that each of us, instead of being individually, hermetically sealed in the story, is part of a larger group that's watching the same thing, facing the same mirror.

The moment which actually I think I'm trying to capture in the book and the moment with all these voices, these people sharing the experience they had watching these films — what it represents to me is the moment when you walk out of the theater, out of the darkness and into the lobby, and you hear everybody around you talking about the film, talking about what they loved and hated, exchanging meaningful looks, even talking to one another because when somebody says, "Oh, that was hilarious," there's something uninhibited enough about where you are when you come out of that darkness that allows you to talk to strangers and say, "I love that moment, too." That for me is what turns an audience into a community. For me, as an Asian American, that maps out to my own experience growing up in a largely white neighborhood, realizing there were other people who shared similar experiences as me as I grew older, and then, finally, emerging into something that felt like a community at college and beyond. That's the reason I wrote this book.

That's phenomenal. All right. Jeff, why don't you tell people a little about the book and where they can find it?

You can find the book at independent bookstores anywhere and everywhere, as well as the massive platforms online that sell them at deep discounts. The book itself was from Hachette Books. Black Dog & Leventhal was the actual imprint. It came out October 20, 2023. I'm on book tour now. If you're reading this, I'll be in San Francisco in mid-December, in New York in mid-January and lots of places in between and around those dates. Hopefully, I'll see you guys in person.

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Numlock News to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.