Numlock Sunday: Jim Ottaviani and Maris Wicks on women in the space program

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition. Each week, I'll sit down with an author or a writer behind one of the stories covered in a previous weekday edition for a casual conversation about what they wrote.

This week, I spoke to writer Jim Ottaviani and artist Maris Wicks, the creators behind the newly released nonfiction graphic novel Astronauts: Women on the Final Frontier.

The book tells untold stories of women in the space program. It covers the Mercury 13, the group of women who successfully passed the physical trials undergone by the Mercury 7 but never made it to space. It covers people like Sally Ride and Mary Cleave, and how their paths into space were made possible. It also tells the broader story of societal change, how the big, inspiring moments are earned because of bigger, slower cultural shifts going on all the time.

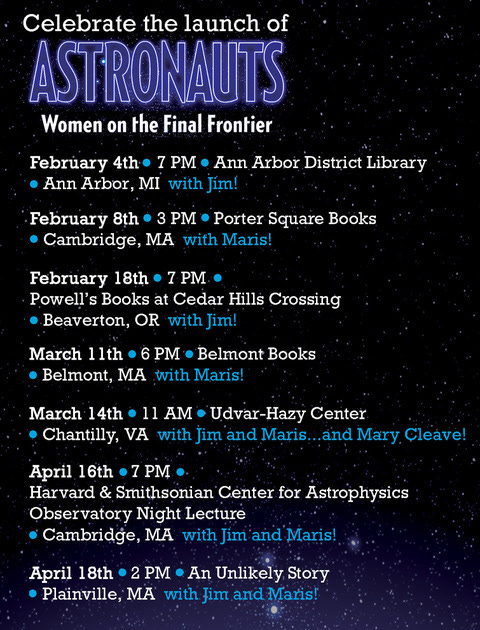

Maris can be found on Twitter, Instagram and her website, Jim can be found on Twitter, Facebook, and his site, and Astronauts can be found wherever books are sold, Amazon, Indiebound or anywhere else. They’re also doing a bunch of in-person events that can be found below.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Walt Hickey: The book is Astronauts: Women on the Final Frontier. It's a graphic novel telling the true stories of some of the women who led the way into space. What got you interested in this topic?

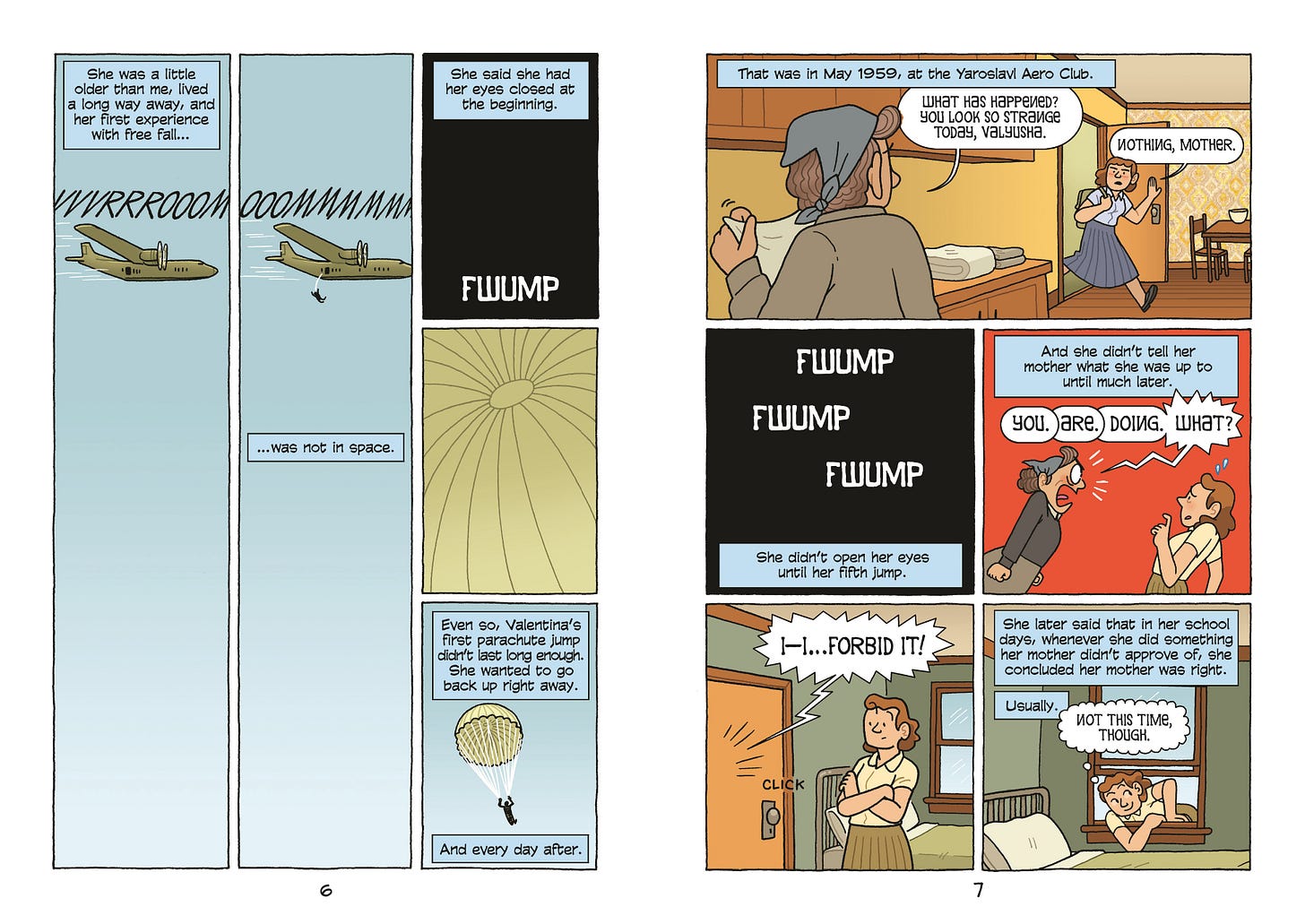

Jim Ottaviani: I did a book about 10 years ago called T-Minus, which was about the space race between the Soviet Union and the United States. I had not too many pages to cover a whole lot of time, a whole lot of space. And in the course of doing the research for that book, I ran across scans of characters that really merited their own book, frankly, they couldn't be squeezed into the current narrative that you're working on.

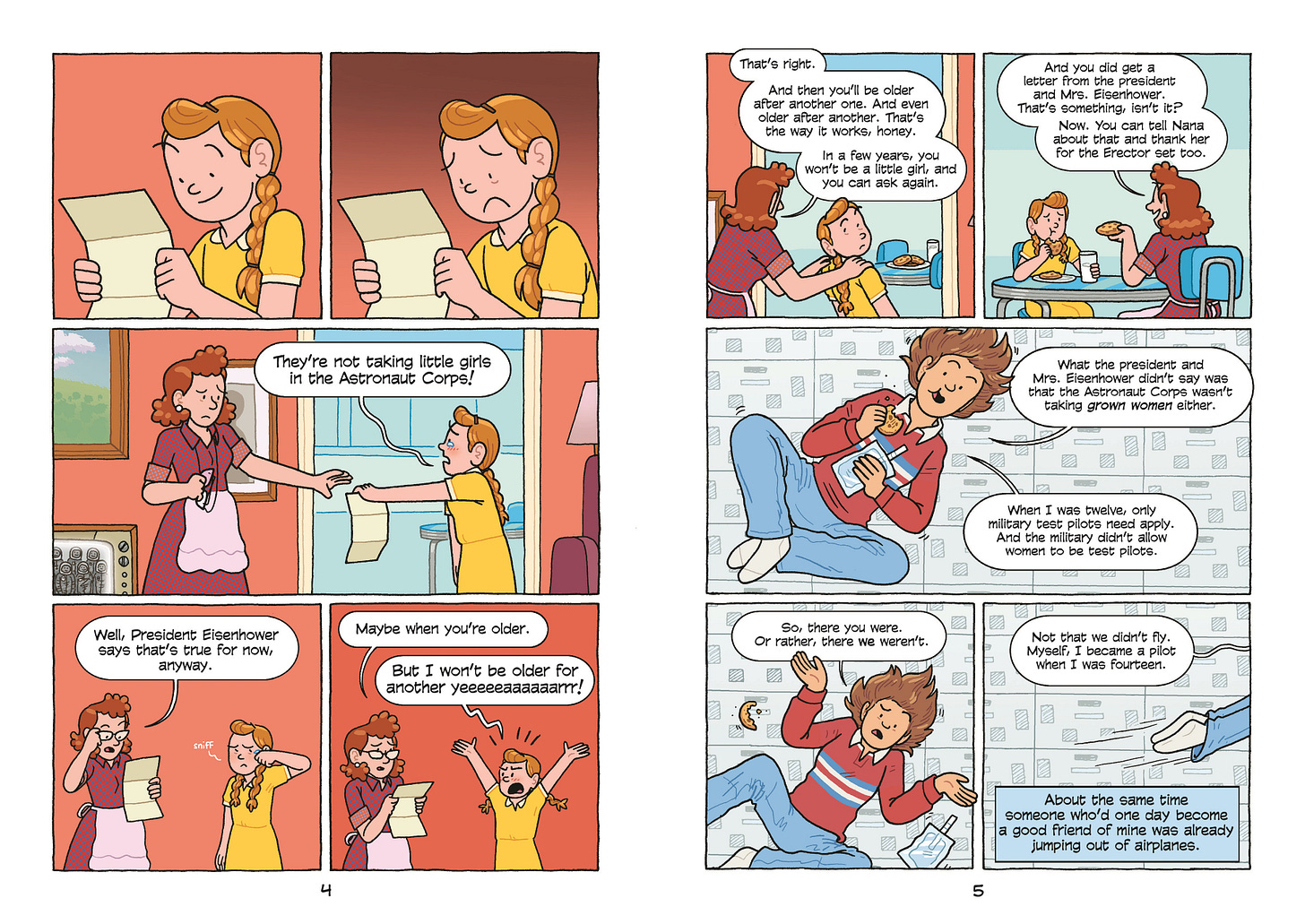

One of those stories was about a group of women who were offered the opportunity — kind of on the Q-T — to take the same physicals that the Mercury astronauts were given. There were 13 of these women who passed it easily. But they were completely stymied, based on a combination of the usual things that you would expect, the prejudices of the time, the prejudices of the institution, some real challenges that were technical that needed to be overcome.

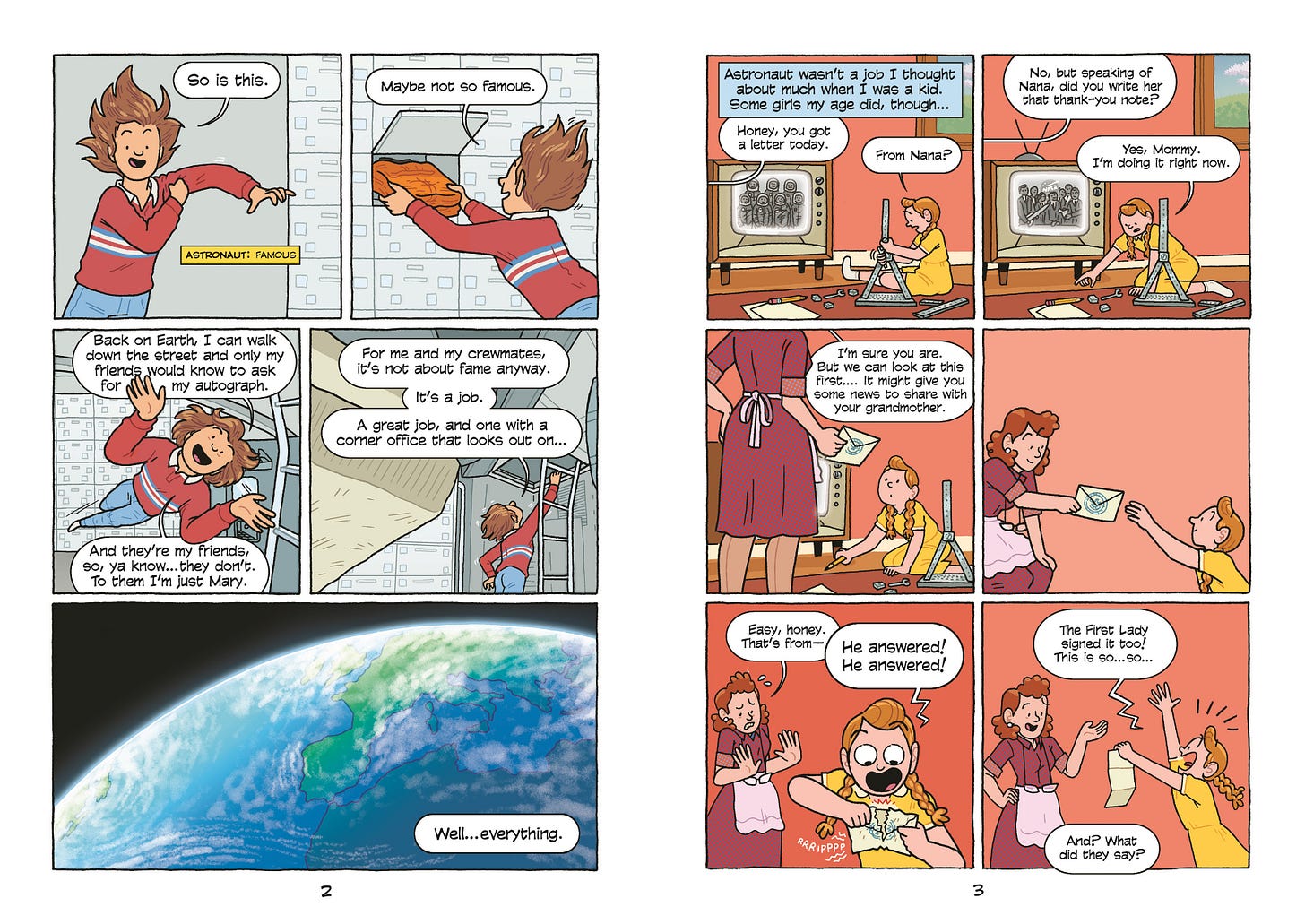

The Mercury 13 women didn't get to go any further, but the story of women in space doesn't end with them. A couple of them pushed things both politically and technically to get the ball rolling and paved the way for other women to go into space. That story got left on the cutting room floor, so to speak, but I knew I wanted to get back to it at some point and this was the opportunity to do so. They are the first major group of characters that you meet, besides our main character Mary Cleave, who does end up going into space.

Maris, what got you interested?

Maris Wicks: When I first realized that science comics were a thing and that I wanted to do them, Jim was one of my favorite writers. This was when I was doing mini comics and zines. We got to work together before on Primates and that was a dream job. As soon as Primates ended, I was like, "Jim, can we do another book?" He had mentioned the ideas of doing a women in space book. There's so much history and story that is crammed into 160 pages and it was an absolute joy to draw. I'm also a tech nerd, so I really liked drawing the shuttle. The inside of the shuttle, those pages were some of my favorite things to draw. I'm such a vehicle-head.

When you are writing a comic book about astronauts, I gather that it is very, very easy to find cool protagonist who lived an amazing life.

Jim Ottaviani: Oh yeah. I mean, all of these people, I hate to use the word overachiever because I don't think they think of themselves this way. Maris and I had the opportunity to hang out with Mary. And I don't think it's false humility, "We're just, you know, people who do the interesting job." But to get to do that interesting job, you go through this hiring process, and then for a lot of people somebody says, "Oh, you know, Walt, you're, you're a really, really excellent writer and we like your work in neurosurgery and we're really big fans of the charitable organization that you started to save millions of people from deadly disease, but we just looking for a little bit more." And that's astronauts, all the way through. Remarkable people from start to finish, basically, and even more so now than during the Apollo era or the Mercury era, where the premium was on individual technical skills, largely centered around piloting. But now everything you do in space is collaborative and requires a team, especially for these long-term missions. So not only do you have to have more than one skill, but you also have to be able to get along with other people.

One thing I loved about your book was that it would've been really easy just to focus only on like the most famous Americans that you can think of, like Sally Ride and whatnot. You go to a couple of really resonant stories that people might not be so familiar with.

Maris Wicks: I didn't know who Mary Cleave was, and it's a great reminder that when you're the first, you get a lot of attention. But then after there's countless people that are doing the same things and then more than what you did, but they don't get that attention of being the first. This idea of showcasing the history? History is chosen by whoever is in power who wants to tell that history.

Jim and I have the ability to look at the history and be like, "what do we want to showcase? How do they want to showcase it?" To a certain extent you are in control of looking at what's been overlooked, what's been forgotten. The fact that I didn't know who the Mercury 13 was is a problem, I thought. I think I should have known who they were when I was a kid. Searching for these things that exist but haven't gotten the attention is at this point a responsibility of people who are telling stories about history.

Jim Ottaviani: A person who Mary put us in touch with was Carolyn L. Huntoon, who ended up directing the Johnson Space Center for awhile, and was the first woman to do that. And it was long ago. It wasn't like 10 years ago. This is 30-some years ago where she was doing this. I didn't know who Carolyn Huntoon was. It turns out she's a delight as well to talk with on the phone and hear her story about being the boss of all these Type-A personalities that flow through NASA.

And I think one of the other things is as Maris and I were talking about doing the book and talking about who to focus on and why I thought Mary would be a good protagonist, one of the reasons was that everybody knows the first people, everybody knows the famous people, but those superstars are so rare and so distant oftentimes that they're not as relatable, and as a reader and as an author, I think let's make the super-famous people there, but not the focus, because that's the way most of our lives are.

That actually reminded me of a scene that I really, really loved in the book. You had a lot of historic events in here, but one of them I think was really cool because of the way that you handled it. Can you tell me about the first conversation between two women, one in space and one on the ground?

Jim Ottaviani: There's an earlier scene in the book where a bunch of Congress chumps were talking about how ridiculous it would be to allow women in the space program, and just imagine them trying to fix something physical. Just making fun of the way they imagined women astronauts would communicate with each other. Later, we get to the point where Mary, our main character, is CAPCOM, the capsule communicator, the voice on the ground, talking to Sally Ride during her first shuttle flight and they've got to talk about stuff. And this happens in the dead of night, but reporters find out about it the next day, and then they ask the stupid reporter-type question, "So what did you two gals talk about?" or something like that. And Mary just dumps a paragraph of tech on top of them. And the reporters are completely flummoxed. They have no idea what she was talking about. I'm going to refuse to give away the punchline on that scene.

Maris Wicks: I should note that this was the first time I ever met, in person, the protagonist for the book that I was illustrating. Mary in real life is awesome, and she is witty and just she's really sharp. Like not acerbic, she has an amazing sense of humor. So, to try and get some of that with body language and expression and obviously Jim's script was helpful as well, because I think he did a great job of translating kind of some of her her like tongue in cheek wit fantasticlly. What's nice is it's not hubris at all, she was just doing her job. And I think that's kind of the best part: she said I was asked one of those questions after two women spoke from ground control the space. So that is like a momentous occasion, but she kinda didn't even realize it until the reporters told her that. She was like, "Oh. Yeah." It was really, really fun to cartoon someone that I had met and interacted with before.

I really was taken aback by the diversity of experiences that you endeavored to highlight. What was it like illustrating that and doing the research? I mean, it looked like there was a ton of research that went into some of these technical drawings.

Maris Wicks: For Primates, most of the references were still photographs or journals or books that I read about the people in that book.

But NASA has so many freakin' documented things. Like for both of Mary's shuttle missions, there's debriefings that are 20 minutes long that chronicle everything that happened on the shuttle and it's filmed. So I could go and actually look at these things. When they talked about all the science experiments they ran on the STS-61B, her first shuttle mission, I could actually look at those and draw them realistically. For me, that's important. I know that I can fudge some stuff because I draw cartoony, but it actually helps immensely.

Drawing people like Sally Ride and Catherine Sullivan and then also even Nichelle Nichols, I was able to find pictures from that Star Trek convention that she first goes and sees the lecture from NASA guy about the early shuttle. That was helpful, but then also super exciting, because there's a light to seeing film and even color photographs that help me to depict who these people are and their interactions with other people. Like the scene with Katherine Sullivan and Sally Ride when they get issued their personal toiletries, what do they called it, one of the bags they get —

Jim Ottaviani: Personal preference.

Maris Wicks: Yes! So it wasn't just reading the transcripts of that happening, it was reading accounts and then also looking at photographs. Yeah. And I definitely fangirled out about getting to draw. I mean, I know we talked about how it's not all about Sally Ride, but I was also like, "Oh my God, I get to draw Sally Ride!" I was so excited.

Jim Ottaviani: I don't mean to poo-poo the famous first folks, they had an extra level of so much attention and I think Neil Armstrong and Yuri Gagarin and Valentina Tereshkova handled their fame in such admirable ways. I don't think we could have asked for anything more from any of them.

Any last thoughts on the book?

Maris Wicks: The thing that dawned on me after I'd finished illustrations, I really love its place in the history of the space programs because it does a really good job of encapsulating the shifts from individual achievement to group teamwork. Because it spans from the ‘60s to the ‘80s, and I think there's so much social change that happened during those two decades that is not at the forefront of the book, but it's in the background that I feel like you get a really good sense of those 20 years and I love that about it. That was one of the reflections I had about the book after completing it.

That's cool, how you can see implicit social progress just in the margins.

Maris Wicks: You're living day to day and progress is being made, but it's really hard to sometimes see the forest from the trees presently. So it's almost like a bit of hope to be like, stuff seemed impossible in the ‘60s, and then look at, look at 20 years later. When you step back from time, you can see change in a way that is heartening.

Where can folks find the book?

Jim Ottaviani: My favorite place to buy books here in Ann Arbor is at Literati. It's a local independent bookstore. That would be my favorite place for you to buy it as well too, if you have one.

Maris Wicks: If you're interested in getting a book and then also getting it signed by either Jim or myself or both of us, we're doing a bunch of events doing in New England, and Jim's doing some, and we're doing a couple of events together, both in Boston and then also in DC.

Astronauts: Women on the Final Frontier can be found wherever books are sold, Amazon, Indiebound or anywhere else.

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Thank you so much for becoming a paid subscriber!

Send links to me on Twitter at @WaltHickey or email me with numbers, tips, or feedback at walt@numlock.news.