Numlock Sunday: John Jackson Miller on the biggest year in the history of comics

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition.

This week I spoke to John Jackson Miller, who wrote “Comics and graphic novel sales grew over 60% in 2021” for Comichron. Here's what I wrote about it:

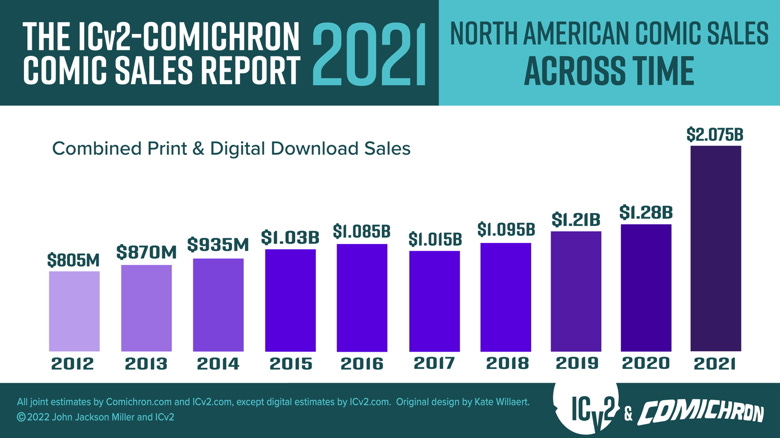

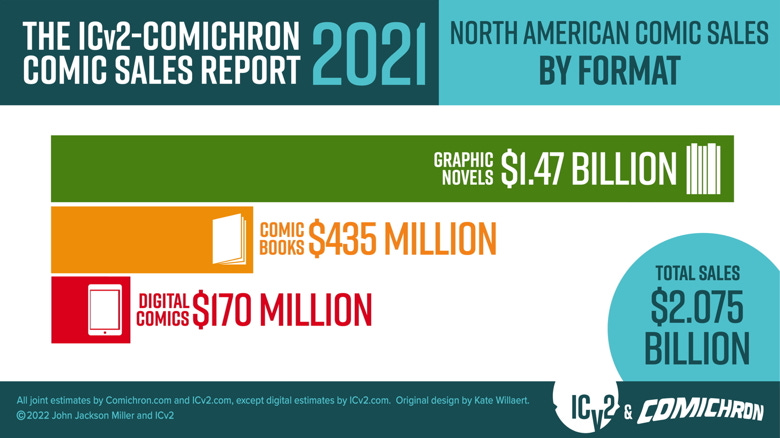

Last year the total market for North American comic book sales on both print and digital download hit a breathtaking $2.075 billion, significantly more than the $1.28 billion logged in 2020 and a massive spike in the relatively stable market for comics. The 62 percent increase in sales is staggering, not only in light of the recent comic sales; the most recent high-water mark for comic sales was 1993, when $1.6 billion worth of product was sold. The robust sales of graphic novels — alone $1.47 billion last year — drove the surge, nearly triple the 2016 values.

John is absolutely one of my favorite people to talk to every year — definitely check out our previous conversations. I think his Comichron project is an absolute gem and his insight about a market I personally find fascinating — comics — is off the charts.

Just in time for San Diego Comic Con, we spoke about the unprecedented pop in sales and why it’s coming from unexpected areas, how the business reshuffling in the pandemic has fundamentally changed the level of disclosure we have about the comic industry, and what’s driving the changes.

John can be found at Comichron, on Twitter and he’s the author of a new book coming out this winter, Star Trek: Strange New Worlds — The High Country, as well as a really delightful library of work in the universes of “Star Wars,” “Star Trek” and more.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

You come out with an annual report along with ICv2, talking about the North American comic book sales market. This is a hotly awaited report for me. I am always fascinated by the change of the market. This year, the numbers were off the charts. We'd seen some growth, but nothing quite like this. Can you talk a little bit about what happened in the North American comic book sales market?

Well, it's almost literally off the chart, because I had to adjust the height of all of the bars on the trend line so that it would fit in the graphic. What happens here is the total dollar value of comics content sold in North America in 2021 goes above $2 billion, $2.075 billion is the exact number, up from $1.28 billion in 2020, which is, as we've observed is already the pandemic year, even that year was up over the previous one. The dynamic here was different. In 2020, the graphic novel portion of the market — the books moving through the book channel, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, bookstores — those fared better, whereas there was a drop in traditional comic book magazines, because the number of comic books being released in 2020 went down due to the pandemic.

There is a recovery, not a complete recovery, of the number of comics released in 2021, but the number of comics sold goes up dramatically to 94 million comic books. The dollar value of those comics goes up to $435 million dollars. That's a significant increase. Digital has a slight increase over 2019. They're both ahead of where they were pre-pandemic, and then the graphic novel market just explodes in 2021, and a large portion of that is manga. You have major titles like “Demon Slayer,” which are extremely successful. You also have continued success of Scholastic's comics line, with titles like “Dog Man” and various other things. We just have something here where the numbers were a lot higher than we've ever seen in the time that we've done this report.

Then I went back and looked historically to see where $2.075 billion racked up against previous years from before when I was doing this report with ICv2. There are two high-water marks in comics history. One of them in the modern era is 1993, which is the peak of the comic shop glut that we had, where there were a dozen distributors helping to open up as many stores as possible. This is that era where we get a big wave of comic book speculation; this is the era where Image Comics hives off from mainly Marvel and immediately out of the gate is very successful. It's clear that 2021 sales beat that year adjusted for inflation. That year adjusted for inflation was around $1.6 billion; here we're over two.

Then I went all the way back to the cloudy history of the early days of comics. And we generally believe that the high-water mark for comic books as a mass medium, the magazine format, is in the early 1950s, and of the highest estimates that I believe are credible at all, nothing really goes over the idea that there were more than a billion comics sold in a year. And that billion comic books would've been sold for 10 cents each, and adjusted for inflation, 10 cents gives you something like $1.50 or a $1.60 these days.

It's simply not able to catch up with a market where the largest portion of sales last year were graphic novels; $1.47 billion came from graphic novels and these are not going for 10 cents, these are going for $10 minimum. So the units back then are dramatically underpriced compared to the units now, and nobody pretends that there are as many copies in circulation these days as there were then, but certainly there's more revenue in the business adjusted for inflation.

It's incredible. One thing that I love about this report and also your work in particular is that it illustrates just kind of how misunderstood the comic book market is. We definitely saw comic book movies fuel interest in some of the big two, but I think what's so interesting about this report and what you just kind of said is that last year was not a banner year for comic book movies, and the growth in the industry is not coming from those traditional big two distributors, or I should say Marvel and DC. Do you want to expand on that and what's truly driving this market?

Well we had hits coming from other publishers besides Marvel and DC, and that is aided in part by the fact that over the last two years of the pandemic, the distribution system has not disintegrated, but it is fragmented. So it is in various distributors' interest to push what they have available to push. There are more people trying to create hits from different places, but I think that one of the things that's great about just the comic book medium is there are so many different ways to consume it format-wise, and also so many different genres; some genres are more prevalent in other kinds of stores than others.

In the last year or so, there's been a pushback against including manga in these figures at all, simply because these works were not generated in North America, but we've never cared about that in tracking. We only care about whether they're printed in North America, whether they're sold in North America — those two things must be true for it to be considered part of the North American market. Viz, which is the publisher of a plurality of the really big titles in manga, it's been in our chart since 1986. It's something where, we have never cared that Alan Moore was sitting in England when he was writing “Watchman,” we have never cared that “V for Vendetta” was published overseas before it was published here, we have always had publishers like NBM that were taking works from the European market and translating them and selling them in North America.

They've always been part of our market; all we care about is a book has got to be defined as comics in the sense that it is a combination of pictures, panels, word balloons — you know it when you see it. But this is something we've been doing for years and years and years. There are titles that may have some illustrations in them, but unless it's a story that is being told sequentially with pictures, it's not a comic.

Comichron, for folks who are new this year, is an incredible resource. It is a historical record, unlike any other on the internet. I'm a gigantic fan of it; you do some incredible work. One thing that we've been talking about for the past three or four years is the data is starting to get kind of weird.

You alluded to it earlier when it came to how the distribution system was really kind of overturned in a lot of ways during the pandemic. But I know that the quality of data that you're getting now is drastically, potentially worse than it was even in the ‘80s and the ‘70s. Do you want to talk a little bit about some of the challenges that you're facing now when it comes to collecting and maintaining this database?

Sure. There are essentially three major ways that we have gotten sales data about comics over the decades.

The first is the one that most magazines have used forever: advertising audit services, where these audit bureaus will report on the number of copies that a publisher sells for the consumption of advertisers. It's something that we had in comics for many decades, but then that slowly went away as advertising in comics went away and in the 2010s, both Marvel and DC dropped their audit services, so that spigot is turned off.

The second source has always been the post office. If a comic book sold through the mail at the periodical class rate, they've had to do a filing that appears in the magazines. I have almost all, I think I lack two or three, of these little statements that have appeared in comics since the 1960s that have the sales figures in them. But what happens again is as subscriptions die out as part of comic book circulation, we have publishers that are just no longer having to report that data. That data is now all gone with the exception of Mad Magazine. It is the only one that I still have a complete record from 1960 to now of their reporting. Mad Magazine is not even putting new content in the magazines, but I'm there once a year to make sure I get the new sales chart, the new sales figure from it, so that's the second stream.

And then the third stream that Comichron is probably most famous for archiving is the sales numbers that come from the direct market, or rather the comic shop distributors. Diamond and precursors like Capital City, which actually, Capital City was co-founded by Milton Greene, who is my partner. He's the principal at ICv2, the company that we partner with in this annual report; he is the one who began reporting sales figures that his distributor made with the intention and purpose of allowing retailers to know what was in circulation, what's out there, is this book really rare or not? That's information that consumers have longed to have over the years. So I made it available and others have made it available before, so that the consumers can also sort of defend themselves and say, "Okay, this thing is not really limited. This thing has a million copies out there," or something.

What happens is this data is of extremely high quality for about 23 years, while Diamond Comic distributors has all of the major comics publishers under exclusive contract. From from 1997 to 2020.

Ah, 2020.

That's right. And in April of 2020, because Diamond has been forced to shut down because of the pandemic, Diamond does not ship new comics for something like six weeks in an attempt to protect the retailers so that they didn't have to get billed for comics that were showing up at their stores when they couldn't open. What happens is DC Comics defects from this system, they set up two retailers as two major mail order retailers as distributors, and they pull their distribution from Diamond. It's now just one distributor that remains from this called Lunar, but Lunar has never shared DC's statistics. It's their position that they can't do anything unless DC allows it. And so for the first time, since 1974, we can't prove that DC is in second place behind Marvel. In a sense, this could be considered a feature and not a bug, and it's never been clear from the beginning that this was intentional though, I don't want to make that case.

Certainly starting up these distributors was challenging, but it's still the case that we're two years in and there's nary a head of data from Lunar. What happens in October of 2021, is a consequence of an announcement that Marvel made earlier in 2021, which is that following suit, Marvel pulls its distribution from Diamond and takes it to Penguin Random House, which has decided to jump into comics distribution, opening a brand new warehouse dedicated to periodical sales. People have asked why Random House would do this. I think part of the reason has shown itself in the last few months, because now having gotten Marvel's single issue business, its periodical business, it's been announced that Random House is now getting Marvel's graphic novel business, their graphic novel distribution to the book channel, to the bookstores.

Everything is going to be consolidated at Penguin Random House for Marvel. What this does for the numbers is that Diamond is still selling Marvel comics as a wholesaler. They're getting their comics from Penguin Random House and selling them, and they have appeared in Diamond sales charts alongside the comics that they sell exclusively, like Image and Boom and Dynamite and other comics. But the problem is we're now only getting a portion of Marvel sales, exactly what portion it's something that I've been looking at and looking at and looking at, and consulting with people on at this point, it's around a third probably.

But now we have a situation where instead of having 100% of comic book distribution at one outlet, now we have basically a situation where Diamond is shipping about 40 percent of the comics in the market, DC is at Lunar, and so that's about 29 percent, and then the balance is coming from Penguin Random House. It is trifurcated, and while it is possible to reverse engineer what Marvel got from what Diamond is able to report, that is less than optimal. I compare it to a lot of things, but a good analogy might be website tracking for analytics programs, when suddenly Apple makes it impossible to track its devices, or you have some change to the code, that means you can no longer pick up mobile devices or something like that. It's something that I have talked with publishers, I have talked with people on the distribution side where they would like to get this information back.

Because as you say, we know less about comic book periodical sales now than we did at the dawn of the direct market, at the dawn of the comic shops, and that is not good. The problem simply is now we're dealing with multinational corporations, when there was a previous fragmentation of distribution in 1996, I was able to negotiate a resolution. It's a much different thing when we're dealing with, I guess Discovery and Disney.

It's just a completely different, again, I think one of the most interesting kind of threads throughout our conversations over the years, has just been how idiosyncratic the comic book market was for the longest time of how you basically had a few producers, one distributor, and then a billion actual retailers.

It just seems in that situation, it's the retailers and the consumers who tended to have a lot of the power in the arrangement. Then one of the big evolutions particularly in the past few years, as a result of the pandemic, has been the two major corporations that produced these comics, have really seized a lot of the autonomy and kind of hidden some of the data about what they were doing, is that a decent assessment?

Yes, and it's caused me to reflect on my goals for the Comichron project. I have always said that I'm an archivist first, an analyst second. My plate is full enough just trying to get all of the figures that I've got all the way back to the 1930s online and in some sort of a situation where people can draw information from them. You have always had this fire hose of data that has been regulated into something that I could still consume. It was in one stream where I could at least report on that portion once a month. And then with ICv2, during the past decade, I've been able to help shape that into a larger picture for the overall market.

Now there's all these holes in the fire hose where it's spraying all different directions. It puts me in a position of saying, "Well, I've got 85 years of data. I can focus more on those while at the same time I have all sorts of readers who are dependent on knowing what's selling now." So I have been working to balance that with my time. But I think whatever happens, the consumer is in a somewhat better place now than in say 1993, where at least now we still have some data coming from Diamond. We kind of have a notion of at least the possible scale of how high some of these titles can be selling. We have differences in that we can look at eBay and get a sense of what the real rarity of some things is on the aftermarket side.

We can look at the population report, the census of comics that have been graded by CGC, which is a major grading corporation for comics, so even though we may not have nearly the complete information that we once had about how many comics initially existed, we still have places that the consumer can go to, the collector can go, to sort of see, okay yeah, this really isn't that rare. The hope, though, is that the publishers would recognize that this is something that they really are, I would say morally responsible for providing. If you are in the business of selling a limited edition collectible, you need to say what it's limited to.

Backing out again, it is always so great to check in with you, this is a really outstanding report. I would definitely encourage folks to check out Comichron and then your partners over at ICv2. John, where can folks find you? I know that you got a book in the works coming out soon, but what's up with you?

Okay, well, the new book is Star Trek: Strange New Worlds — The High Country. That is the first novel for the new streaming series by Paramount Plus. It is coming out from Gallery Books in hardcover, ebook and audiobook in February 2023.

And people can find me, my fiction work is on farawaypress.com. My fiction Twitter is @jjmfaraway, and on Comichron I'm at comichron.com, the website. Comichron is also the name of the Twitter account, the Facebook account and the Patreon account.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Numlock News to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.