By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition.

Joining me this week is Rebecca Boyle, a science journalist with an eye pointed up, covering the fields of astronomy and the history of it.

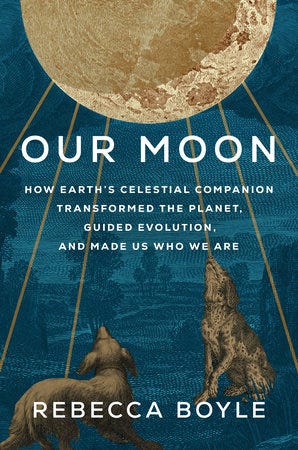

She is out with a brand new book Our Moon: How Earth's Celestial Companion Transformed the Planet, Guided Evolution, and Made Us Who We Are, and I have been looking forward to this one since it was first announced. It’s a delightful look at our planet’s moon, and the outsized role it’s played in the development of life and society and science here on Earth. It’s now available wherever books are sold. I hope you enjoy our conversation.

The book is available wherever books are sold.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Rebecca, thank you so much for joining us.

Thanks for having me.

You are the author of a brand new book all about the moon, and I just think that this is such an amazing topic. What drew you to the kind of area of talking about our moon?

Yeah, so I am a lifelong moon enthusiast, I guess. I've always loved the moon ever since I was a kid. I remember being in I think fifth grade — I remember the building, so I'm pretty sure it was fifth grade — sitting in the floor of the library listening to a vinyl record of the Apollo 11 recordings and just being blown away, like, they were actually there, they were on the moon?

And as a kid it just sort of took my breath away and it kind of still does. It's really a crazy thing to think about. It's so wild that we actually did that. And I sometimes think about how weird it is. Even as a kid it was like, wait, what? We walked around up there? Why? What for? And I still feel that way. It still feels like this sort of strange thing that we decided to do to cross this boundary between us and the moon. And I never left that connection, I think. A lot of kids like the moon; it's in so many bedtime stories, it's sort of a thing that accompanies you in childhood, and I think adults maybe move on from that, but I never did. So that's why I wrote this book.

In terms of things that kids can see, that adults see, that basically the entire human race sees, it is one of the most interesting dynamic things. The sun? Very cool. Ten out of ten, we're all big fans of the star. But the moon changes, and it makes it, I think just fundamentally more gripping and interesting sometimes than anything else in the sky.

Yeah, I think that's right. And it changes on the timescales that we live our lives. It changes every night, and so do we, but it changes in this pattern that we can use. And I think people have figured out really early on that that was a good way to tell time and to orient ourselves in time. I think humans are the only species that does that, really. There are other animals, squirrels can squirrel away stuff for fall and we know animals can plan, but that's a sort of biological planning that's driven by other cues. And as far as we know, there's not this complex squirrel culture where they sit there like, “Oh, hey, it's September 1. We better start getting ready.” But humans have done that and I think the moon is the reason we could. It was the first thing that allowed us to sort of situate ourselves in time.

And it changes on scales that you can use, but you can also think about it philosophically. The sun rises and sets every day, the seasons come and go over longer time frames, but the moon goes away and then it comes back, and it comes back in the same pattern. And I think that's a really interesting thing to think about if you're trying to grapple with things like eternity and returning and death and renewal. The moon is such a good avatar for those things and I think that's what early humans latched onto about it, and I still use it that way. I still think about it in that sort of sense where we trust that it will come again.

Yeah. I want to take a little bit of a step forward, not just a step back, because I feel like it's been kind of fun talking about this heady concept of what exactly the moon is and does for us.

But you are a science writer, this is a science book, and so much of this is grounded in just the scientific manifestations of what this celestial body reflects on our world, whether it's animals or evolution you write about. And so I guess from a scientific perspective, what were some of the angles that you pursued in just writing the book about the moon?

I mean the evolution stuff was so surprising to me. I kind of had a sense that we all know the moon pulls on the Earth; that's why we have the tide. I think most people probably know that, that that's why we have the tide and any ocean on Earth, that the height of the water relative to the beach changes every day, rises and falls, because of the moon's pulling on it. And so I started thinking about that and was like, well, surely it has some role.

And I found this interesting study from 2019, but the fossils in the study were from 400 million years ago. These scientists looked at these coral fossils, which were sort of like tree rings where you can date times and you can unwind the clock by looking at these coral fossils. And they figured out that at that time, 400-some million years ago, the day was 20 hours long, which means that the rotation of the Earth was faster than it is now. It's slowing down because the moon's moving away from us. And I felt like that's weird, and if the moon was closer, it probably had a stronger tide and it was probably messing things up.

It turns out that it was, and it was around that time, I guess a little after that, so about 300 million years ago, give or take, and this is when Pangaea is starting to form. So ocean basins were closing up and the tides in these little narrow ocean inlets were just extreme, like 80 feet between high and low tide, which is only a few hours. Right now a tide is about six hours between the high and low tide and we get two a day because of the way the moon moves around the Earth. But back then it might've been, like, maybe it was five, because the moon was closer. So five hours of time, and there's like an 80-foot shift in the height of the water. And if you're a fish hanging out in shallow tide waters, you better be really quick to get out of there or you're going to get stuck.

And it turns out that they did. These really extreme tidal areas are correlated to some of the earliest tetrapod fossils, which are these fish that learned how to walk, basically, and either pull themselves out of the water or pull themselves back into the water by using their fins like how we would use legs. And these are the first animals that ever did this. This is the lineage that leads to all other back-boned animals on land — us, dogs, elephants, everything comes from these tetrapods that were stranded by the moon, basically. And I never knew that was such a strong connection, but it's very clear in the fossil record and that kind of blew my mind.

That's amazing. There's this idea that ancient tetrapods wriggled up on dry land by their own volition and dragged themselves out from the sea, but in fact they were just yeeted by the moon into having four legs.

Yeah, exactly. And they're like, “Oh my God.” And then they had to learn how to breathe and they had to learn how to move, or they would've died. So the ones that didn't die are the ones that lived to pass on their genes, which are the ones we have to thank for being here.

So without a moon, there's so much of just the history of the development of life that just would not have happened the way that it did.

Yeah, I don't think it would've happened at all the way that it did. And maybe it wouldn't have even happened. I mean, one of the other things I learned about this was that the moon dredges up the ocean, like a ladle in a pot of soup, and it sort of stirs it around. If we didn't have lunar tides, especially when the moon was closer a long time ago when life was first emerging, it wouldn't have mixed the ocean like that. And so all these nutrients that would feed the chain of life, and still do, would just sort of sink to the bottom of the ocean and just chill there. So it would be a desert, and the ocean would be really dead.

And probably the first life that evolved, everybody pretty much thinks it came from the ocean. Whether it came from tidal areas is kind of debated, or whether it came from very deep ocean like hydrothermal events is a more common theory now. Either way, the moon would've dragged this stuff around; it would've brought it to the surface or brought it to the shore or brought it higher up in the ocean where it could have reached sunlight and started to learn how to photosynthesize. All this stuff probably wouldn't have happened if we didn't have the moon here acting on us. And even if it did happen, it would've been very different.

Beyond life, what are some ways that the moon has changed the Earth itself?

So it's really lucky for us that we have it because, I mean as we all know, we have seasons because the Earth is tilted on its axis. And that means that as we right now in the Northern Hemisphere, we're just past the winter solstice, so it's winter, it's cold, but as we go around the sun, our tilt will sort of tip us back toward the sun in the north and it'll get warmer in spring. That stability of that tilt over time is possible because of the moon, because it sort of keeps us stable gravitationally. So Mars does not have a moon like this. Mars has two little dinky potato-shaped rocks that orbit it, but they're not really moons in our sense. They don't do anything to Mars.

It's pretty embarrassing.

It's kind of sad. I feel bad for Mars. Mars is like a failed planet in many ways. Poor little Mars, it just couldn't hang on, and neither could its moons. But our moon keeps us safe, and Mars is kind of screwed because it doesn't have a moon like this.

So Mars tips over sideways, essentially, every 10 million years or so, give or take. Mars’ axis now is about the same as ours, it's like 23.5 degrees, but in a few million years it'll be like 40 degrees. That would be Earth tipping over so that the poles are almost facing where the equator is now. And that would melt all of our sea ice, and it would dramatically change the climate of Earth. And that's what happens on Mars. Mars gets these terrible cycles of enormous amounts of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and Mars is kind of out of luck. So we're lucky the moon doesn't let that happen here because otherwise it would be very difficult to have evolved.

It's also a bit of a bodyguard against objects that could potentially crash into Earth, no?

Yeah, it is, and I think it's a bodyguard in that it sort of takes some of the beating that Earth might otherwise get, but it also protects us from this chaotic orbit that Jupiter would knock us around like a bully on a playground pushing you over and shoving you out of the way. Jupiter's gravity would really mess with Earth. And because the moon is here and it's so big relative to Earth, it doesn't let Jupiter do that. It's kind of like our little protector.

Jupiter can be kind of a jerk and it can sometimes send asteroids at us and it kind of messes up the whole solar system, but the moon is here to keep us safe.

That's really nice.

So we've talked a little bit about how it influenced some of the early developments of biology on this planet, and some of the other stuff. You write about how it had a very significant effect on human understanding of time and also just the development of civilization. Do you want to speak to some of the more sociological elements of what the moon’s done for us?

Yeah, so I think I kind of started with the idea of time because it's sort of the most obvious connection we have to the moon. The month is from the word “moonth.” It's like an Old English word. The moon really is the reason we have months, and the reason we have a seven-day week is because we divide up the month by four. There really are four lunar phases, which is why when it looks like a half moon, it's called first quarter, which is sort of a misnomer, but it's the first one-fourth of a lunar cycle, and that's about seven days. So that's why we have seven-day weeks.

All of that stuff was interesting to me and I kind of wanted to figure out more about how people figured that out a long time ago before written language. And it turns out it was hard. It was really hard to fix the lunar months against the solar year because there are about 12 moons in a solar year. So from the time it takes the sun to go back to the same place on the horizon between solstices, there are like 12 full moons or 12 crescent moons. But there are only 354 days in a lunar year in those 12 moons, and there are 365 days in a solar year. So you're pretty short pretty quickly; over a couple of years, you're off by a month. And if you plan your calendar with a lunar cycle, you're like, “Oh, we're going to do our harvest festival in October.” Well next year it's like November, and you missed it and you're screwed. And so people had to figure out how to fix that and sort of marry those two calendars. The 12 days of Christmas is actually a holdover from that tradition.

Really?

People just tacked on 12 days. It's called the Twelvetide. They're like, “The year is over, that was the last moon, but we're not quite there yet, so let's add 12 days and just hang out.” And there were parties around it, and other cultures added a day here and there, a month here and there. Now we have a leap day every four years, and that's in part because of how we mark the solar year, but also in part because of how long it takes the Earth to actually go around the sun. But anyway, the point is that we had to figure out this complicated relationship and it was hard to do that. And I think one reason people developed things like written language was to be able to figure that out better. Once that happened, people kind of created civilization, and the moon guided all of that.

I think people, after some time, started ascribing more meaning to it and being like, “Oh, it's helping me.” It's like, “I can see at night, I can protect my sheep, I can travel longer distances and I can get to where I'm going. Thanks moon, please help me out.” And then that transmutes into the first forms of religion, which people had. That all originates in the Sumerian era, which is the people who first emitted written language and are the bedrock of civilization, Western civilization, and they were really devoted to the moon. A lot of current religious traditions still follow some of their same ideas and their same rituals and their same kind of structures, which come from this early, early moon devotion. Some people later on—

Like what?

Like altars and sacrifices and practices that are intended to appease the moon god or give it gifts or place it in honor.

There is this poet I have in the book who's probably the first person to be credited with writing something, and she's this mysterious person who was thought to be the daughter of Sargon the Great, who was the first emperor of Earth. He's the first person on Earth to unite these different cultures in one large geographic area in what's now Iraq and Iran. And he kind of brings together these different city-states and rules over all of them, and he installs his daughter as the high priestess of the moon god, which is the most important thing in the entire Sumerian pantheon.

But she's from a different city where the most important god is Venus — and what we now call Venus had different names back then. Inanna was the Sumerian name for this god. And she figures out how to connect them for people in this really ardent poetry, this really devout poetry. Some of it is so familiar sounding. If you grow up with any religious tradition, with how people pray, some of the language that people use even now really goes back to this priestess, Enheduanna, this Sumerian moon god priestess. And I think the moon hasn't really gotten enough credit for stuff like that, for how much it played a role in that.

Yeah, I mean I love the cultural side of it and obviously a lot of my interests are in pop culture, and I don't think it's a coincidence that some of the earliest films that we made and some of the most remarkable science fiction writing involved a journey to the moon and that kind of stuff. Its resonance in culture and top of mind-ness I don't think is a coincidence.

No, I totally agree. And I was surprised about some of the genesis of that stuff. Any book about the moon is going to have to include people like Galileo and Kepler and all these old white men, and they really were super important in developing our understanding of the universe. But I didn't realize how much Kepler mattered in terms of science fiction. He kind of originates the idea of science fiction. He has this story called Somnium, which is “dream,” and he travels to the moon and meets this culture of moon people who live there and have these rituals where they watch the Earth change in their sky and they have all these devotional practices to it and they're all superstitious and they have to live in caves to stay out of the sun, because the lunar day and night are two weeks long and they have to somehow protect themselves.

And so it's just a super involved kind of fever dream, and it's really the first piece of science fiction. And so much science fiction follows that. Almost all of it early on is about the moon because we could imagine going there, it looks like it's right there, it looks familiar. Even early cartography, what we knew the continents to look like by the middle of the 17th century, probably, you could sort of almost imagine the moon having the same structures where it's like, “Oh look, there's the sea over here.” People thought they really were seas. And there are splotches that are still called “maria,” which is the Latin word for “seas,” because people thought they were oceans just like we have. So it makes sense that people were like, “Oh, I could totally go there and it wouldn't be that hard.” It's just right there. And all the early science fiction is based on that; it's like how we do it and how we get there, and why? What are we going to do?

And then we ended up actually doing that, in fact.

And then we actually did it, yeah. And I think even the Apollo is so deeply connected to science fiction in ways that I think we tend to forget now because it's so far in the past. But the people who built these rockets were super interested in science fiction and literally developed the technology to do it based on early science fiction work by people like Jules Verne. His book From the Earth to the Moon is kind of the seminal lunar fiction. And it's really good. I read it writing this and I was surprised how much I enjoyed it because you think of Jules Verne as being like, it's just old-timey, whatever, but it's super entertaining and funny and really acerbic in certain spots and it's a whole allegory... I didn't realize this before I read it, that it's an allegory for the post-Civil War era.

The whole point of the book is that all these Civil War people are like, “Well, we have all these guns and big cannons and stuff, and what should we do with them after the armistice? What are we going to do with all these weapons?” And one guy's like, “Oh, let's put somebody in it and send them to the moon.” So that's what they do.

And of course that would liquefy you if anyone tried to actually shoot an astronaut out of a cannon. But that was the kind of reason why, they're like, “Oh, well we have all this weaponry, let's shoot for the moon,” quite literally.

Yeah, I mean I'm built different, so I probably would be just fine. So the events of 1969, how did that change humanity's relationship with the moon to the current day?

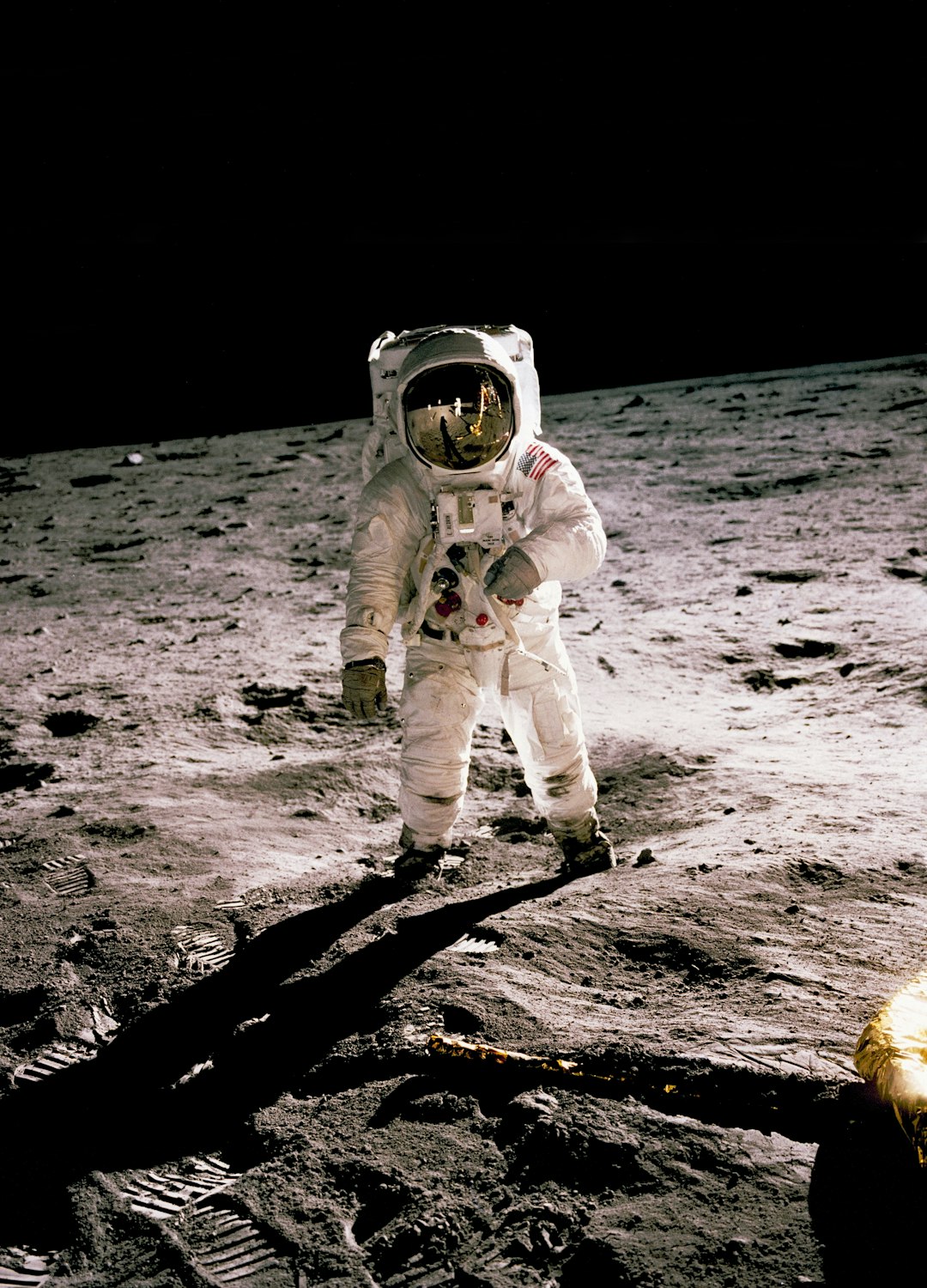

Yeah, I think about this a lot, and I go back to this picture that I have in the book and that you can find on Google, but it's one of the pictures from Apollo 11 that's not the most famous picture. The picture people recognize is the boot print and the dust and the one of Buzz Aldrin standing there with Neil Armstrong reflected in his helmet, or the one of Buzz Aldrin saluting the flag. Those are super, super iconic images.

But my favorite is this picture of Buzz Aldrin climbing down the ladder to join Armstrong on the surface. And it's kind of a weird picture because it's like, he's on the ground taking it looking up. So Buzz Aldrin's leg is hanging out above you. And it's such an active picture, but it's, to me, so compelling because somebody else took it. A person was on the moon for the first time and Neil Armstrong and his camera were there looking out as opposed to the entirety of human history where we're somewhere else looking at the moon, looking down on it. Now someone's there looking up out back at us, which to me is so crazy to think about. It still blows my mind.

Apollo is such a long time ago now that I think it's easy to take it for granted and like, oh, it was a cool thing we did back in the day, but just think about that for a minute, how weird that is. Let's just send some guys up there and check it out and maybe we'll bring some stuff back and check that out. Hopefully we don't bring home a lunar plague. We don't know. We better hope there are no big bugs that are going to eat us. And they didn't know they were even going to be able to land. They thought it was quicksand. All these questions that people had until literally the Apollo missions, people didn't know what the moon was. And then all of a sudden we're there and we're on it and now we can perceive it in this totally different way.

It's interesting because again, it feels like on some level that we never really got over it. It still is one of the wildest things that we've ever done, but then we also really did never do it again. And then clearly now there's an ambition to get back there, but it does feel — not to diminish the potential for science to be done on the moon, there are always still new things to do, to slightly diminish the "economic case" for it. But it is just kind of a true voyage, a bit romantic. A thing that is truly just in the spirit of exploration. And it is interesting that we're going back.

I think that it’s totally worth doing for that reason. I love the idea of people just being like, "Let's go check it out, man. Let's go get some rocks and look at them and try to study them." Talk to a scientist and they'll tell you, "I want impact melt breccias," and all these terrible geology words.

But then they’ll really slow them down and talk about, why do you want to know about the moon? What do you want to know about how it formed? And you hear these just incredible stories about the violent day that the moon was formed when it was shorn from Earth, and how we know the history of bombardment of the solar system by looking at the craters of the moon, and all these different stories.

I feel like some of the people going back now, there's a lot of interest in making money up there and how can we create a new lunar economy and all these things that I think are probably a lot more far afield than people would like to admit, first of all. But also, I don't know if that's the main motivation we need. We needed the Cold War to go the first time. That's why we went. It was to show off how smart Americans were and how Western capitalist ingenuity could get us to the moon as opposed to the Russian method of living. And it worked, so I guess it paid off.

But the real benefit of Apollo wasn't that; it was science and it was what we learned about the moon and ourselves. And I think that's still a good reason to go. It's still a good reason to go romp around up there. I think it's a better reason than going to extract some stuff and to use it. That makes me a little bit sad.

Yeah, I think you're allowed to be romantic about the moon. Like we said, it's one of the most dynamic things that we see in the sky.

So I guess as it stands, again, you wrote this book, it's out now, and it's just kind of a big look at this thing that we have a very interesting relationship with. Is there anything that you'd like to close on? Anything that you found particularly interesting from the book that you think folks will enjoy?

I want to go back to this story that sort of opens the book, which still surprises me that I hope will surprise people, which is the role the moon played in World War II. The war is probably the most compelling thing in the last century to have happened, and the most devastating thing and the most important thing to have happened. And I don't think people know — I didn't know until writing this — how much of a role the moon actually played in this.

There are two big battles that happened in the war where the moon was key. The first one my grandfather was part of, and this is in the South Pacific in the Battle of Tarawa, which is now part of Micronesia. This island was a really important airstrip for the Allies to take in the whole campaign to invade and defeat Japan, but they didn't have good tide charts back then because nobody really had done that for the whole globe. And there were no satellites yet. This is before Sputnik, even.

There were no satellites. So we had no way of measuring all of this.

There was aerial photography, maybe.

Yeah, at best, and boats. So the Marines used tide charts that were developed by seafarers from the 1800s and/or data from the coast of Chile where the tides are totally different, and they just had no idea.

And they were making a best guess about, okay, well this moon is first quarter, it's going to rise at this time and it's going to be a high tide at 11 a.m. and it'll be enough water to get our boats over this reef that we need to get across to invade this island.

And they were wrong because they didn't know the moon was further away in its orbit. It's the opposite of a supermoon, it's a micro moon, and it looks tinier because it's just a little bit further away than average. So the tide is weaker — it didn't have a strong enough pull. The water doesn't come and the Marines get stuck on this coral reef and just get obliterated. And it ends up being the worst battle in the history of the Marine Corps.

Oh my God.

Three thousand men died in this battle, and my grandfather was there and he made it. He was in a different detachment and came later. But I knew he was at Tarawa when I was a kid, and I heard these stories growing up. He didn't like talking about it, like a lot of veterans, but I kind of knew some of the basics about how he prayed in these foxholes — he was a devout Catholic — and how he got through the war.

I never knew that the moon really was a huge influence on that battle and probably on his whole experience of the war and then the rest of his life, which kind of blows my mind. And I use that example just because we all have some kind of personal story like that about the moon, and maybe they're more obvious. Maybe it's like you remember looking at it one night, or you're on a date or something, or it's really pretty. Or maybe it's this personal narrative that you never really thought to pull out and to understand, and that was mine. So I hope that people think about their own when they read it.

That's incredible.

All right, well hey, where can folks find the book and where can folks find you?

Anywhere books are sold, hopefully. Go to your local independent bookstore and ask for it. It's out from Random House. There's also an audiobook narrated by Rebecca Lowman, who does amazing work. And you can find me on all the social channels. I'm on Twitter or whatever it's called now less than I used to be. But yeah, if you just search Rebecca Boyle or @RBoyle31 on any social network, I will be around.

Amazing. Well, hey, thanks for coming on.

Thanks so much for having me. This was fun.

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Numlock News to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.