Numlock Sunday: Sam Ro, the Quitter and the TKer

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition.

This week, I spoke to my former colleague and longtime friend Sam Ro, one of the smartest people covering finance and the economy. Sam wrote a really great post recently called 4.3 million quitters and me 👋 to launch his new newsletter, TKer (pronounced Ticker) all about what’s been going on in the economy. Here’s an excerpt:

A record-high 4.3 million workers quit their jobs in August, according to BLS data released last week.

That number represents a record 2.9% of total employment in the U.S. As a percentage of total separations — which includes layoffs, firings and retirements — quits reached a record 71.1%.

It seems the so-called “Great Resignation” is accelerating.

People are quitting low-paying jobs for higher-paying jobs. People are quitting great jobs for even better jobs. People are quitting to become their own boss. People are quitting because they don’t actually need the income.

I have been an avid reader of Sam for a while and it’s great to see him get back to posting on the regular. This Sunday, we talked all about quits, inflation, and why the problems the economy has right now aren’t exactly the worst problems, and the fundamental optimism at the heart of economics coverage.

Sam can be found at TKer.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Sam Ro, you have just started a new newsletter called TKer. You had a post that was blending both economic data about how people have been quitting their jobs at extremely high rates and some personal information, like that you have been quitting your job at extremely high rates. Can you talk a little bit about what's been going on in the broader economy and then kind of how that connects to you?

Yeah, sure. It's funny, it's one of those instances where the big economic trends collide with the writer who's reporting on the trend, or analyzing it, or trying to get a better understanding of what's going on. But at the same time, it's also not something that's too rare.

The economy is made up of people. We are all participants in this economy and the decisions we make inform and impact what's going on in the economy. So that's a setup to this initial weekly newsletter that I put out on TKer called, “I quit two jobs within months because of the economy.” This is something that has been written about a little bit over the past few months, but continues to intensify.

Last week, there was data that came out of the Bureau of Labor Statistics that showed the number of people quitting jobs is the highest on record, even as taken as a percentage of employment, which adjusts for population and all that stuff. The percentage of employed people that are quitting is also at a record high. There are a lot of things that are going on here. With the pandemic, of course there are folks who are certainly concerned about the spread of the virus, and related to that, there are folks who are having a rough time maintaining a job while trying to figure out childcare. We all know that the schools are all kind of messed up and it's not easy to find a babysitter or a nanny, especially now with so many folks having a sort of weird work-life situation.

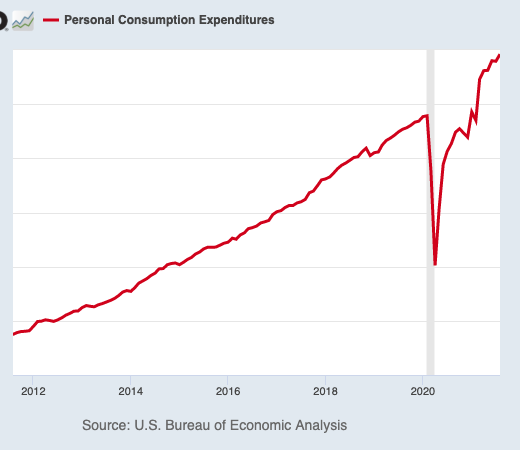

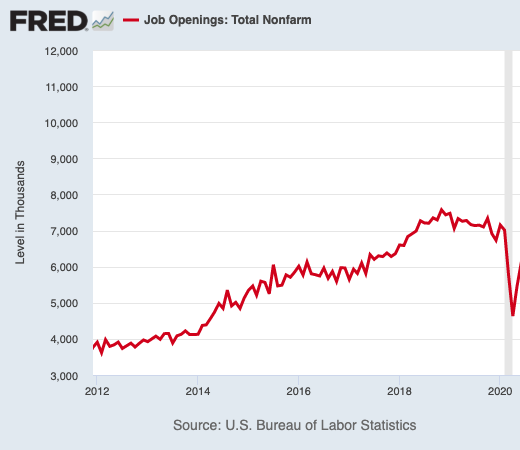

That has also collided with an economy that is on a very sharp rebound from where it was about a year and a half ago, when the pandemic forced the economy to essentially shut down. Thanks to things like stimulus and loose monetary policy, the economy went from shutting down to opening up and that's all been aided by things like better health and safety standards, as well as the distribution of vaccinations for COVID-19. So the economy has been rushing back, but the economy has been rushing back from a demand standpoint, faster than people have been able to return to work or people have been willing or able to return to work. So what you have now is a whole bunch of employers who are scrambling to fill jobs because demand is so strong.

What that has actually done is it's put pressure on employers to raise wages and give better pay to folks in an effort to attract people to their companies and their businesses so that they can conduct business. You have folks who are actively working, who are seeing these job postings. They're seeing all these listings out there. There are over 10 million job openings right now. They're seeing all these, they're seeing the numbers, they're seeing the pay. They're seeing all their friends take these new, higher-paying jobs amid this booming economy. And so they themselves are putting themselves out there. They're applying for new jobs, they're getting jobs and as a result, they end up quitting their current job, which feeds into this data. So quitting, the statistic about quitting is one side of a pretty complicated function here.

While there may be millions of people quitting, not all of them are necessarily getting new jobs. Like I said before, there are folks who are quitting because of safety issues. There are people who are quitting because of childcare issues. And then there are folks who, it turns out that they actually didn't need this job. Maybe they have a spouse who's earning enough money that it can support the household, and so, they'll quit and they won't return. I think there's like an estimated two million people who retired earlier than expected amid the pandemic who may or may not be coming back to the workforce. It's been interesting times, but one of the real interesting statistics that has emerged in the past few months or since the pandemic has started has been this extraordinary jump in the number of people quitting their jobs.

And the way that you've been describing it, you actually — a post came out on Friday that kind of alluded to this, like, “listen, there are absolutely problems in the economy here, but they're also not the worst kind of problems to have,” right?

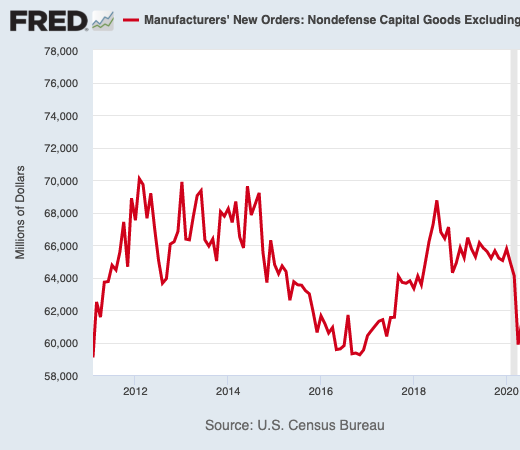

Right. I characterize them as high quality problems. One of the challenges that comes with employers trying to fill these positions is this whole matter of the economy booming faster than the economy is able to address that demand. It is causing things like the prices for certain goods and services to go up. Because people aren't returning to certain factories or people aren't returning to certain kinds of jobs, those businesses and industries aren't able to produce the products and services that the economy is demanding. When you have less capacity, when you have a limited number of goods going to a whole bunch of people or businesses, it creates this situation where suddenly the people who have the capacity to pay more will pay more.

Of course, if you run a business, if you sell a product, if you sell a service and you have less capacity, you have fewer goods to sell, you actually have no problem raising prices, because in the past, if you raise prices, you risk losing some customers. But because you don't have the ability to serve many customers to begin with, why not raise prices to the few people who you are able to serve? And so what we have is prices rising in a lot of different pockets of the economy because of those mismatches, but it's something that seems to be a situation where these mismatches have been caused by the fact that we do have these issues that should reverse eventually. Eventually, things like supply chain disruptions begin to sort themselves out as people return to work.

Listen, there are so many different things gumming up things like supply chains, which is causing inflation. But if it persists for too long, then suddenly it becomes an opportunity for some entrepreneur to come in and take advantage of that, and in the process make that cheaper for everybody in the long run.

But to get back to your question, yeah, we do have this situation right now where this economic boom is also having these less favorable consequences, like prices rising for certain goods and services.

You had an interesting post about the inflationary pressures, I want to say a week ago. It actually really helped me like, reorient how I think about stuff.

I've had this problem where like, I'm kind of cheap. And if I want to buy a thing that I know for a fact that I need, like, I know for a fact that I need a new laptop, the other one's running on nothing, but I will wait and wait and wait and wait until the price goes down and never buy it. But in this post, you were alluding to that mindset as, that's why deflation is a problem. So, you would rather kind of have inflation because it definitely motivates you buyers, “oh, I should get something right now rather than wait.” Do you want to get into that a little bit?

Like I was saying before, inflation is currently a symptom of an economy that's booming. Inflation is not necessarily great, especially if you are breaking even, or you're squeaking to get by, or you have a lot of expenses. Maybe you are in an unfortunate situation where you don't have a lot of income. Inflation can be incredibly painful because obviously the prices of the things that you're going to be buying are going up. And this is not a great situation, but you also wonder about like the alternatives, right?

Another alternative scenario that comes up from time to time is this idea of deflation, when the prices of stuff are going down. Now on the surface, that sounds like a great thing. Like who doesn't like it to see things get cheaper, but you have a couple things that can go wrong when the prices of things start falling. First of all, like you were saying, if I see something go from $100 to $90 in a week, and then the next week, it goes to $80, what's got me rushing out to the store to hurry up and purchase this thing? Why not wait another week to see if that price actually goes down to 70? And so that behavior that comes with people just waiting to see how low a price goes actually reinforces that trend; it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

You and I might decide to sit on the sidelines while something goes from 90 to 80 to 70. And we might both be able to afford this thing, but because we're waiting, the fact that we're not going into that person's store is going to force that business owner to cut the price to 60 or maybe 50, or maybe it suddenly goes to cost, and they're just hoping to break even. But again, if the price keeps flying down, then suddenly this person is like thinking, well, I got to make rent. I got to pay interest payments on the business loan that I have. And suddenly they'll start selling inventory at a loss because they have certain fixed costs that they need to address. And let's not forget that business owner might have employees who now have to be laid off because, well, first of all, there's nothing that's selling.

This is a sort of very extreme example of deflation, but this is the kind of thing that can happen in an economy where things are falling apart. This is something that we were actually facing a year and a half ago at the onset of a pandemic. The entire economy shuts down and everyone is locked down, they're at their houses, but all these stores have just gotten all these shipments for all these goods because they're expecting some people to show up. And so what happens when that demand dries up? That was certainly a scenario that we could've faced where prices keep spiraling and things sort of run out of control.

I think the last thing I'll mention about inflation versus deflation — this is actually very important. When it comes to prices rising because people are sort of in this frenzy and they see the price of something going up or that the supply of something is running down, they're going to rush out to stores and hurry up and buy the stuff before they miss that opportunity. This is something that happened with toilet paper a year and a half ago where suddenly, there was plenty of toilet paper, but this idea that there might not be enough, suddenly you buy two rolls instead of one.

When that behavior starts to get out of control or starts to get a little worrisome, we do have policy makers, like the Federal Reserve who can intervene in the economy. It's not something that I think most consumers notice directly. It's not very obvious, but they have the ability to come in and tweak some things in terms of how money works in the economy, where they're able to raise interest rates and increase the cost of financing. Suddenly, there are these little things that happen, whether it's corporations or business owners and stuff where it just gets a little bit more expensive to go out and do whatever it is that people were doing that was causing this inflation. With deflation, I guess in theory, they could do the exact opposite. They can lower interest rates and make things cheaper and incentivize people to go out and make those purchases.

But it's a little bit different because with tighter monetary policy in the face of inflation, when you don't have money, or when they make it less affordable to buy something, you just flat-out cannot buy something. But when they're trying to stimulate the economy amid deflation, all they can do is tell you that yes, you can afford this. It's cheaper now. But they can't ever force you to buy something and reverse your behavior. So there's this idea that it's much easier to get inflation under control as opposed to trying to reverse the sort of devastating effects of deflation.

So the moral I'm taking away from this is that the economy is complicated and it would be really nice if there was some sort of person who could help explain it. Do you want to tell people about TKer?

Yeah, sure. TKer basically was born out of lots of conversations I've had with a lot of both readers, and people on Twitter, and people emailing me, as well as friends and family and stuff. I think especially if you've ever been an expert, or if you've ever been a subject matter expert, or if you work in any particular industry and it's in the news, you always have that friend from college who sends you a text message and asks you what's going on.

I was very much in one of these positions myself many years ago before I got into finance, where I see all these headlines, I see a lot of news, and I know there's something really serious happening, but one, I cannot keep up with all the headlines. And when I do try to follow the news and the information, I don't know what's what. I don't know what is out there to scare me. I don't know what's out there to help me. I don't know what is important to understand, and I don't know what's not important to understand. And so with TKer, the idea is to stay on top of the news, and the data, and the statistics that inform sort of longer-term, more consequential themes when it comes to the markets and the economy.

There are a lot of interesting stories that happen with businesses and certain parts of the financial markets and niche parts of the economy that are like really interesting that I'll definitely read, I'll definitely click on, but are not necessarily going to move the needle when it comes to things like inflation, or employment, or home prices — or importantly, stock prices, things that are critical to your retirement savings, or your children's college funds and stuff like that.

That's sort of what TKer is really all about, is to sort of scale back on the noise that comes with a lot of the news that's out there. To be clear, I'm not trying to like, replace news, but some people are just busy and we're all busy. We can't watch everything, we can't read everything. And we can't spend the time to become informed so that we can navigate and sift through all these things. With TKer, what you'll see is me writing a lot about things that are very newsy. It's something that someone says that day that's impactful and moving the markets. Or I write a lot about economic data that gets released, either quarterly or monthly, and how this information relates to bigger themes in the economy, in the markets.

The idea is to be able to provide a service or some readings or like a website that you can go back to where you don't have to sift through 100 stories a day. You don't even have to expect to read more than one thing every two or three days. It's a website you can come to, it's a newsletter you can sign up for that will every once in a while, send you information, send you news that will help you get a better understanding of what's going on in the economic and financial market world that matters to you.

All right. That seems as good a place as any to end on. Anything else you wanted to get in there?

No, that's really about it. But Walt, thanks for catching up with me. I'm obviously a big fan of Numlock.

If there is one thing to really keep in mind, it’s that for hundreds of years, thousands of years, however far you go back, it is actually the case that people and societies and economies are all trying to figure out how to make things better, make the world better, make their lives better, make things more efficient, make their living standards better.

And so while we might see a whole lot of headlines and stories that seem really worrisome and concerning and might have you all very gloomy about things, it's actually the case that people are working their butts off to make things better. And all that stuff is actually reflected by things like economic data and financial markets and the stock market, which have been going up for decades. And so if there's one thing about TKer and just the flat-out truth about how financial markets and the economy work, it’s that it's something that requires some optimism, and it's not as scary and it's not as troubling as you might assume.

I like that. That's a good spot to end on. That's a good vibe.

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Thank you so much for becoming a paid subscriber!

Send links to me on Twitter at @WaltHickey or email me with numbers, tips, or feedback at walt@numlock.news.