Numlock Sunday: Uri Bram, Person Do Thing

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition.

This week, I spoke to my friend Uri Bram. He’s currently the writer of the newsletter Atoms vs. Bits, and he’s the publisher of the newsletter The Browser.

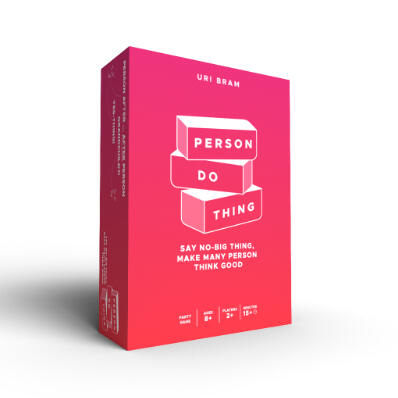

Uri’s been working on a really fun project lately expanding out a party puzzle game he designed several years ago into — Person Do Thing — into full-fledged physical game that he’s been getting made, shipped, packaged and sold to launch this Fall. Being the huge fan I am of his work and just so fascinated by how stuff gets made, I wanted to talk to him all about what it’s like to both design a game and participate in global trade in Spring 2025.

The game’s great, and if you’re into party games like Codenames or Taboo and the like you’d probably dig it and should check out a preorder. Either way, hope you enjoy our chat.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Alright, hey man, thanks so much for coming on. I’ve been looking to get you on Numlock for, I think, years at this point.

I’ve been waiting all my life.

You have so many different irons in the fire, so many cool things that you’ve started or been a part of. I guess I’ll just throw it to you a little bit. What’s your background on this? How did you come to where you are right now? Many people have probably been familiar with some of your work at some point, whether it’s through The Browser or otherwise, what’s your story, and how’d you come to the point that you’re at now?

Yeah, when I graduated college, I didn’t have a job, and I was too embarrassed to tell people that, so I decided to write a book in order to have a thing that I was doing. So I self-published a book called Thinking Statistically. It was like a fun, simple intro to stats concepts, and I just caught the wave when Kindle was opening up. So that became surprisingly successful, and I spent a few years as an author and then a journalist. I was a huge fan of this newsletter called The Browser, which I discovered around the same time. I basically wrote a fan letter to the creator, my friend Robert Cottrell, that turned into me doing some work for him, which eventually turned into me running that newsletter.

The Browser curates five interesting articles every day. We try to see through the trash heap that is the internet, and find five really original, interesting, memorable pieces of writing, and so we recommend those.

I helped start a primary school in Johannesburg, South Africa, and also helped run a coding boot camp there. I run a storytelling consultancy with my friend Peter Hirsch, who was the head writer on Arthur, the amazing kids’ TV show. I once made a website called daysold.com that tells people how many days old they are, that is, in terms of raw numbers, the most impactful thing I’ve done in my life. A lot of people know how many days old they are through that site.

I want to talk about a couple of things that you’ve got going on right now, one of which is a new newsletter that you’ve got, Atoms vs. Bits, that you do with a friend and colleague of yours.

Atoms vs. Bits is a project with my friend Jehan Azad. He’s a nuclear scientist who also makes radar technology for detecting unidentified flying objects. He also runs a wiki for how to restart civilization in case we ever lose all of our technology; how would we get it back?

The blog was just, “Oh, we enjoy writing, we enjoy talking to each other.” We figured we should create a little outlet for all of our strange and interesting ideas. It all began with a piece that Jehan Azad wrote about how MSG is wrongly maligned. We both think MSG should be properly used. It is delicious. It makes food taste better. It especially makes vegetarian food taste better. So if you’re into that, it’s worth putting MSG on really everything.

Along the way, we’ve written pieces about this weird theory that humans are descended from a chimp-pig hybrid rather than just chimps. We’ve written about the World War II-era British propaganda campaign that claimed that British pilots had great eyesight because of the carrots they were eating. Obviously nonsense, but very effective supposedly at misleading the Germans. Yeah, we’ve written about many other things besides.

Awesome. I know that you’ve always been intrigued by puzzles and have always had a foot in that world. Lately, you’ve decided to take a bit more of a leap into it. Do you want to talk a little bit about your personal history with game design and what you’ve been working on for the past little while?

Yeah, I think I’d probably like to ask you questions as well. Are you happy to do that?

Yeah, sure.

I think you’ve had the same experience, right, that people like puzzles and games on a lot of news and media websites are people’s favorite items, right? Supposedly, the New York Times’ subscriber growth in the last four years is largely the puzzle app and the recipe-like app. That is the bulk of their new subscribers, not the news products. I don’t know if I can verify that, but that is what I’ve been told.

I can verify that games are a massive deliverer of traffic, and also on a personal level: I really don’t care for spending time on LinkedIn, but I have been playing the LinkedIn games every day for the past year.

Wait, what is LinkedIn doing at games these days? I completely missed this one.

I’m actually madly in love with the game “Queens,” and they’ve got some fun other ones on there that I take a dabble at each day.

Games are an incredible way to get people on a website that they normally wouldn’t spend time on, but also seem to be a lingua franca of the internet, right? Your early interest in this stuff was always, I think, very prescient.

Yeah, there’s just something about it, right? One of my favorite pieces of writing ever is this thing that Lee Child wrote about suspense. I think most writing advice is useless, but he’s this thriller writer, and he wrote this article about how to create suspense. He basically says that if you create an open question, the human brain just desperately desires to close that loop. And it’s one of these clever pieces where he tricks you in exactly this way while he’s writing it. He keeps giving you these open questions that he hasn’t yet answered, and then you keep reading in order to find out what the answer is. I think this is brilliant, and I try to incorporate it into my writing.

I think this is, in some ways, the heart of a lot of these games. I’m really into “Bracket City” lately, this game from The Atlantic, and even on days when I’m not sure I’m enjoying it, I just can’t help myself. Once that puzzle is open, I can’t help but finish it. So I think it’s tapping into something primal and important.

Yeah, there’s absolutely something that necessitates play in mammals, right? I think that this gets at something a level deeper than our own brains, you know?

Yeah. I should throw in, I realized I do know about LinkedIn Games, because the games editor there is Paolo Pasco, who also writes crosswords for us at The Browser.

Oh, delightful!

He’s one of America’s top crossword solvers, and I believe he stole the title from our Browser crossword editor, Dan Thayer. There’s this tiny but really lovely community of these ridiculously talented crossword solvers.

You’ve got a fun game right now that is absolutely playable in digital form, Person Do Thing. You’re pursuing a physical release, too, and that is just a really fascinating process, top to bottom. Do you want to talk a little bit about the design element of it, and how you came up with it, and developed the game? And then we can talk a little bit about what it takes to actually bring this into the real world.

Yeah, for sure. So, “Person Do Thing” is a very simple game. You have a list of 34 simple words, like “person,” “do,” and “thing,” that you’re allowed to say, and you’re just trying to describe a more complicated concept. So, if you were trying to describe Numlock, you would say, “many, many person, one thing, thing good, thing big good, person see thing, person feel good.”

As you can see, the issue here is that this could describe other things as well, though obviously nothing is as good as Numlock. It’s like a classic game in the mold of Taboo or charades, where other people are trying to figure out what it is you’re describing. There’s a big theory-of-mind problem because it’s obvious to you and obvious to no one else, so you sound like an idiot. Everyone gets annoyed at each other, and everyone has a good time.

I first created this game more than 10 years ago at a cafe in Thailand where I was trying to explain that I’m vegetarian without speaking any Thai. A friend and I were there, and the friend had a few words of Thai, so we muddled through with “no chicken, no beef, no pork,” until eventually the waitress was like, “Oh, vegetarian.” So we started a conversation about the minimum number of words you would need in order to convey all the complicated ideas in the English language. I turned this into a website more than 10 years ago. I actually built an app at one point. I went to a party and met someone who was a fan of the game and was like, “make an app. Take my money. I will throw money at you if you build an app for this.” I discovered that a lot of people will download a free app, and very few people will pay for it.

I believe I had tens of thousands of downloads of the free app, and I think I had three, maybe eventually eight sales of the paid version at $3 each.

So this was a terrible investment, but a good time was had by all.

A year ago, I decided that it was really time to finally produce a physical deck. I obviously think there’s something really fun and special about physical, real-world games that you can pick up, that you can get off your phone, that you can enjoy with friends. So I started that process.

It’s a real fun game. You get a word like “farmer,” and you have a very limited vocabulary with which to describe it. So you have to be among a group of friends shouting phrases like “person make eat thing,” until they get what you’re talking about. We are in a renaissance when it comes to actual physical tabletop games. Tariffs were probably not a thing when you started this out. But what does it involve to actually, you know, get this thing printed on dead trees and packaged up?

It has been fascinating and really fun. There’s been this indie hobby game revival over the last decade or so. Kickstarter, I think, has been a big part of that. And a bunch of pioneering designers who trod this path. At this point, if you want to manufacture a game in China, there’s just a list. You know, you can go online. There are 10 or 20 well-known companies. You email them a little. You say what your game is. For a game like Person Do Thing, that is effectively a bunch of poker-sized cards in a pretty standard box with a little instruction manual, it is not intimidating to any game manufacturer in China. You get a bunch of people saying, “Yep, yep, we can absolutely make that. Here’s your quote.”

I do say China repeatedly, but it is genuinely only China. There’s one company, a Chinese company, that’s starting a facility in Vietnam, I think, and one that is doing one in Indonesia. But historically, it has just been an entirely Chinese business.

To give you some sense of the numbers, a very simple, small card game like this might cost $1 or $2 in manufacturing costs. As you mentioned, since the tariffs have come in, if the tariffs were 145%, you might be looking at $1.50 for the game itself. Then another $2.25 in tariffs when it lands. Now, for a small box game, let’s say a game costs you $2 to make, you might be able to sell it for $20, $25. For the small box, simple games, the manufacturing cost is a relatively small part of the final sale price. So a lot of games like that are still viable even with the tariffs.

Things are different if you have a bigger box game that might cost $10 to produce — something with lots of custom plastic components, something with a more interesting, unique manufacturing process — those things might cost $10 to produce, but might cost $40 to $60 retail. Those ones are the ones where the tariffs basically eat the entirety of that game’s margin. Is this interesting?

It totally is. I think that the mechanics of how it actually looks from a person producing it is a bit unknown. I think that everybody knows that there are markups. But it’s a really good point that any part where the actual cost of the game is front-loaded is a game that is no longer viable to produce in this world. Whereas if you have a game that is built in the course of the supply chain, as yours is, that is actually a more viable way of producing a game under this particular set of challenges.

I mean, the other economically interesting parts are sometimes you buy a game, and it’s in a big box, and then you open the box and it’s a very large plastic insert and a few packs of cards. You’re just like, “Why was this in such an enormous box? This really didn’t need to be like this.” There are a couple of things to this. One is that if you’re selling in stores, shelf space is very important. Shelf presence is very important to which games people actually choose. Basically, you’re making this entire box and filling it largely with air just so that when people see it on the shelf at a store, it jumps out at them, which I think is very funny. As a New Yorker, I don’t have space for these big boxes. It seems like this weird, convoluted setup that harms me as a player in the end.

The other part that I think is really interesting is that psychologically, people see a bigger box and think it’s more valuable. And I think there’s a really interesting analogy here with newsletters, where I think people who pay to subscribe to newsletters feel like if they’re not getting enough stuff, they’re getting less value. We’re trained to think of it like potatoes; if I get more potatoes, then that should cost more money.

For games, much like with newsletters, you actually want less stuff. A lot of the time, I want fewer words. In some sense, I should pay people to send me less email. But, yeah, I think our primitive brains can’t really internalize that.

You also, and we were just talking about this the other night, you were just at a packaging convention of some sort? As a game designer, what was it like to go to that?

Yeah, so, I mean, tariffs really do incentivize different behavior. Everyone in the game industry is looking around, trying to figure out if they can make their games elsewhere, specifically if they can make their games in the U.S. There are a couple of big game manufacturers who exist in the U.S. But their prices are a lot higher, and they also have limited capacity.

The other day I found out there was a packaging convention at the Javits Center in New York. I thought, “Hey, I’m going to show up.” I’m just going to show up and I’m going to find a bunch of box producers and be like, “Hey, you can make this box, right? You have a bunch of cards. Do you think you could find it in your heart to chop up your card and make playing cards? I know this isn’t a thing you do, but maybe this could, yeah.” I had a lot of fun. It was really great. I recommend the packaging industry to everyone. They were very friendly people.

I’m already ordering my decks in China for my first batch. That is already in motion. I’m hoping that we can find some producers who didn’t realize they were in the board game business but are happy to move into the board game business. I will also say some tariffs are definitely pluses and minuses for different people, let’s say. But it was really nice to meet a bunch of manufacturers who were just really happy about the tariffs. I think a lot of these packaging manufacturers are like, “Yep, we’ve got so much more interest. Everyone is coming to us now.” So, yeah, it seems like those people genuinely feel as if tariffs have done them good.

Huh. You found them! Cool.

I found them. Yeah, so another element that I do find interesting is you know… I spent a lot of time making digital products, obviously, newsletters. You just sit there at your computer. You make it. You send it. You don’t have to think about physical reality very much. One thing about manufacturing in China is that the average shipping time from China to the West Coast is about five weeks. To the East Coast, it’s more like eight weeks. You have to go through the Panama Canal, which is annoying and slow. If the price were equal, I would very happily manufacture in Mexico or the U.S. just to save myself the logistics of demand estimation. I need to decide well in advance how many games I need and take on all of that risk.

I think games, like a lot of other industries, are fairly seasonal. People usually sell, I think, 60 to 70 percent of their annual sales in December during the pre-Christmas rush.

Do you want to talk about Amazon? Amazon payola is kind of interesting.

I mean, I would always like to talk about Amazon payola. Tell me more.

If you take a standard product that I’m selling on Amazon, between the referral fees, the closing fees, the fulfillment fees, if you’re selling through Amazon, you’re looking at $8 or $9 purely for Amazon costs on a $20-$25 sales price. You’re dealing with this semi-monopolist. You know, you can sell without Amazon; you can sell on Shopify, you can sell through your own store. But honestly, Amazon is where the customers are. So it’s very hard to resist selling there.

They have varied their prices a lot over the years. In some ways, Amazon’s decisions about its pricing have a bigger impact on me than the tariffs do. The tariffs are only on your manufacturing costs, and obviously, Amazon is charging you some fixed fees and then some fees based on your retail price, which is much higher. Then, beyond that, there's the Amazon advertising issue. A lot of people find that they can’t sell their game unless they pay for the sponsored preferred spots at the top of Amazon’s listings.

You can very easily imagine that you end up with a game where your costs are $15, you’re trying to sell it for $25. A lot of people are spending almost the entirety of their $10 margins, from what I understand, on Amazon advertising, on what is basically payola. It’s just an interesting wrinkle. It depends on the costs; for some more expensive games, the tariffs can easily be $10, $15 as well. But for your smaller items, in some ways, Amazon’s policies are more important than the U.S. government’s.

That’s fascinating. That’s really interesting. As a person who’s launching a new thing, the more consequential thing is not the capriciousness of Washington, but whatever Seattle wants to set the prices at.

It’s interesting, right? There’s Seattle and there’s Washington. I have two governments of sorts watching over me, and both of them have a big impact, yeah.

As someone who’s manufacturing a game for the first time, I don’t really know how much demand exists for this product. I’m in this really tricky spot where if I don’t order enough decks right now, I could easily sell out at Christmas. By the time I can get new decks to the U.S., it’s four months from now. It simply won’t be in time. But if I order too many, I’m going to be in trouble if I don’t sell them.

I think there’s actually a really interesting thing here about risk aversion. I’m fairly sure that most of the indie game designers are ordering too few of their boxes. The pain of ending up with thousands of unsold copies and knowing that you over-ordered is more salient for people than the actual expected value. It’s really bad if you sold out, and you could have sold thousands more copies. In terms of your income, that is probably a bigger issue. But it’s very hard to think that way when you’re just a simple indie designer.

Fascinating. So let’s see if we can help you a little bit with that problem. How do people get their hands on the game? How do they preorder? How do they reach out? How do they follow it?

Oh, that’s so kind. Yeah, so the game is online at persondothing.com. You can play the digital version there. You can preorder your decks at want.persondothing.com.

Listen, I love the digital version as much as anyone, but truly, the physical version is a work of art. It’s just going to be beautiful. It’s going to be so much better; it’s going to be worth your dollars. So you can order there. You can reach me at persondothing.gmail.com. I don’t think I have any social media right now. You can follow me online at Uri Bram. I’m @UriBram on Twitter. I’m always happy to hear from Numlock readers.

All right, man. Thanks so much for coming on.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Numlock News to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.